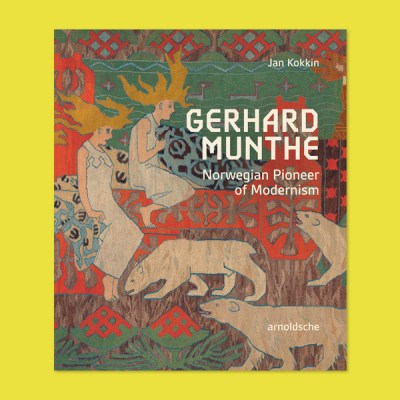

The recent purchase by the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen, of a seven-panel, 30m-long frieze, The Skeleton in Armor by Walter Crane (1845–1915), caused some surprise. On closer inspection, however, the Viking-inspired work is a perfectly logical acquisition in keeping with the museum’s collecting policy and regional interests. The Duchy of Normandy was created in 911 by the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte, when Charles III of West Francia handed Rouen to the Viking leader Rollo. The Normans remain proud of their Norse heritage, as well as of their links across the Channel, so the acquisition of a major work on a Viking theme by an English artist ticks all the boxes.

The Skeleton in Armor (1883), Walter Crane. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

It will also enhance the museum’s holdings of British art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a collection greatly enriched by the bequest of the Anglophile painter Jacques-Émile Blanche (1861–1942). Among Blanche’s own works in the museum is a portrait of Guillaume Mallet, who in 1898 commissioned Edwin Lutyens to design the Bois des Moutiers about 40 miles up the coast at Varengeville-sur-Mer. The house is an Arts and Crafts masterpiece with decorations and furnishings by W.R. Lethaby, Ambrose Heal, Robert Anning Bell and others, and for many years the great Morris tapestry The Adoration of the Magi (now in the Musée d’Orsay) hung on the grand staircase. In 1998, in my role as master of the Art Workers’ Guild, I organised a centennial exhibition at the house, with the attendees at the opening all praising ‘l’esprit de William Morris’. Morris, Crane, Lutyens and Anning Bell were all masters of the Guild, and many of Crane’s illustrated books collected by the Mallet family were on display for the occasion.

The commissioning of the frieze and its subsequent history are well documented. In the winter of 1882–83 Crane was in Rome with his family when he was approached by Robert Nevin, rector of the American Church, who asked him to paint a frieze for the dining room of Vinland, the mansion Catharine Lorillard Wolfe was building in Newport, Rhode Island. As Crane recalled in his autobiography, ‘The subject was to be taken from Longfellow’s “Skeleton in Armour.”[sic] There was an old tower at Newport which was said to be a relic of the early Norse discoverers and settlers in America, long before Columbus, and stones with runic characters incised upon them were said to have been found in the neighbourhood. Others, however, said the reputed tower was only the base of a mill; but the States are not wealthy in antiquities, and it seems cruel to deprive Newport of the interest of such a promising relic. I was desired to introduce this tower into the frieze and I had a photograph of it to work from. There were four lengths of frieze of about twenty-four feet each for the four sides of the room, one of which was invaded by the window heads. I schemed a continuous sort of decorative picture, the incidents succeeding one another without formal break or division into panels, and then painted the frieze (which full size was about three feet deep) in flat oil colour, each length being on a continuous roll of canvas worked upon wooden rollers, around which it was looped, and could be run forward or backwards by handles affixed to the same.’

The Skeleton in Armor (detail; 1883), Walter Crane. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

Crane hired a studio in the Via Sistina and set to work immediately. The incidents he depicted in the seven panels start with the birth of Longfellow’s unnamed Viking hero in a Norwegian forest, followed by his embarkation on a pirate ship, and meeting with the daughter of King Hildebrand, with whom he exchanges vows. The king rejects his suit, thus precipitating the young couple’s elopement and escape by sea pursued by the irate father, resulting in a grand battle in which Hildebrand and his men are defeated. The couple finally reach Vinland/Rhode Island, where a daughter is born to the princess, who subsequently dies; the narrator in his grief then takes his own life and his corpse is found ‘still in rude armor drest’ at the base of the tower. Crane completed the larger panels before leaving Rome and despatched them direct to Newport, while the smaller ones were painted on his return to London. He exhibited The Viking’s Wooing and The Viking’s Bride at the Grosvenor Gallery that summer of 1883.

Catharine Lorillard Wolfe died in 1887, and Vinland passed through several hands before being bequeathed in 1955 to Salve Regina University, a religious college founded by the Sisters of Mercy. Crane’s frieze with its violent scenes was, however, deemed unsuitable, and was dismounted and sold at Christie’s, New York, on 28 October 1987. It reappeared at Sotheby’s, London, in July 2007, and was subsequently bought by a Japanese collector. On resurfacing at auction in Lyon in June 2017 it failed to sell, but the fact that it was in France and available alerted the curators of the Musée des Beaux-Arts, who were subsequently able to negotiate its purchase by private treaty.

After all this movement and having been rolled up for much of the past 30 years the panels are now undergoing much-needed conservation; last autumn the museum launched a crowdfunded appeal to help with this, which raised an immediate €15,000. Although further funds are still needed (and readers are welcome to contact the museum for details on how to donate), it hopes to have the work completed and the restored frieze on public display by the end of this year. This will provide a good excuse – if excuse is needed – for a visit to Rouen, which, with its great cathedral, church of Saint-Maclou and other medieval delights, has always been a place of pilgrimage for British Arts and Crafts enthusiasts following in the footsteps of Burges, Ruskin and Morris.

For more information visit the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen website.

From the February 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.