Apollo’s regular round-up of art market headlines and comment. Visit Apollo Collector Services for expert advice on navigating the art market.

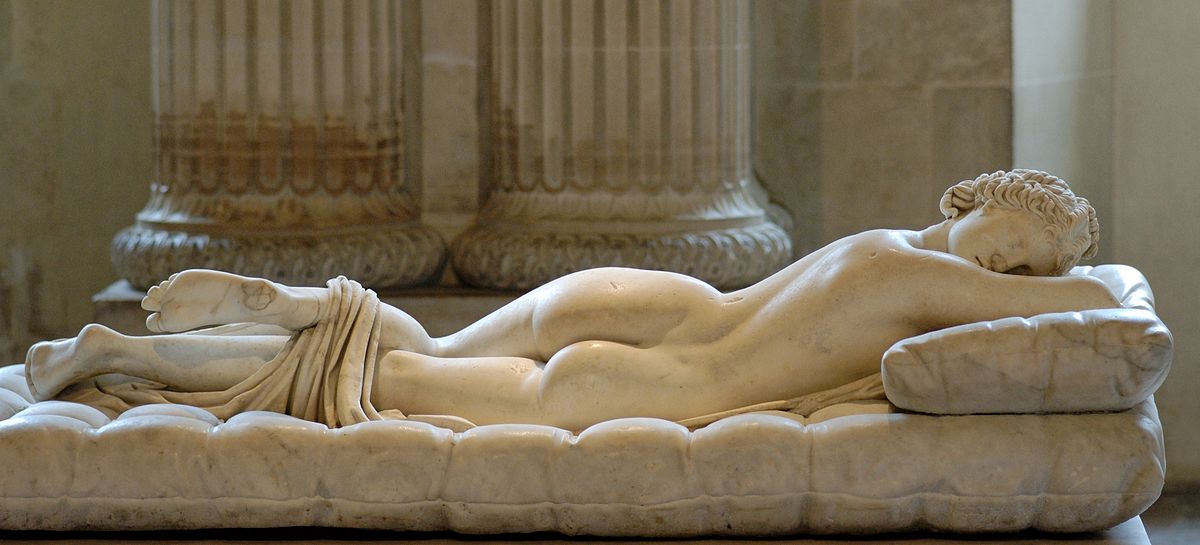

Perhaps Hermaphroditus was doomed from the start. His name, a conflation of those of his parents Hermes and Aphrodite, may well have presaged his fate. The beautiful youth resisted the charms of the water nymph Salmacis who, after spying him bathing, had rushed into the water and clung to him. The naiad implored the gods to keep them forever joined. Her prayer was answered, and the two were melded into a single body with a double sex. Since the cult of the god-goddess gained popularity in 4th-century BC Greece, the idea of the hermaphrodite – always portrayed in Graeco-Roman art as a female with male genitalia – appears to have intrigued us. Horace Walpole’s aunt, Lady Townshend, even quipped that the hermaphrodite was ‘the only happy couple she ever saw’.

Sleeping Hermaphroditus (2nd century), Roman. Musée du Louvre. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Lady Townshend was referring to the famous 2nd-century BC Roman marble of the Sleeping Hermaphroditus then in the Villa Borghese (it has been in the Louvre since Napoleon persuaded his cash-strapped brother-in-law Prince Camillo Borghese to sell him 344 of his antiquities in 1807). The figure had been discovered near the Baths of Diocletian in 1608 and presented to Cardinal Scipione Borghese. In 1619, he paid Bernini for the making of the bizarre buttoned mattress on which the figure now sleeps. At the time, the marble was believed to be a Roman copy of a Greek original by the great Polykleitos. Then, as now, part of its appeal was the element of surprise, and uncomfortable ambiguity, that it afforded: viewed from behind, the figure looks like a seductive Venus. Given that some eight other copies of the lost Greek bronze original mentioned by Pliny are known to survive, it is not unreasonable to presume that there were once hundreds. This one was not, however, the only hermaphrodite unearthed in the 17th century.

A bronze reclining figure of the Hermaphrodite (probably mid 17th century), Italy. Cast from the antique marble restored by Ippolito Buzzi in 1621-23. Christie’s. Estimate £200,000-300,000

A second marble version was first recorded in another celebrated Roman collection of antiquities formed by Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi. Unlike the Borghese figure, this one retains its antique base, and the hermaphrodite slumbers on a tiger skin laid out over rocks. Ludovisi commissioned the sculptor Ippolito Buzzi to add the missing nose and legs in 1621–23, using the Borghese statue as his model. Such was the sculpture’s enduring repute that in 1669 it was acquired by Ferdinando II de’Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and dispatched to Florence where the androgynous figure gave its name to the Sala dell’Ermafrodito in the Uffizi, where it still presides.

On 6 December, Christie’s is offering a bronze cast taken from this figure. Although its source is quite rightly not as admired as the Louvre marble, the piece does by its very material – as well as by its surviving base – more effectively evoke the lost original from which both are believed to derive. A bronze cast of the Borghese Hermaphrodite was also made in the 17th century, ordered by Velázquez in 1650–51 for Philip IV’s new apartments in the Alcazar and from which the artist took the pose for his sinuous Rokeby Venus. The difference between the two casts, however, could hardly be greater.

Matteo Bonuccelli’s bronze for Philip IV is highly refined – dark, sleek and enhanced by gilded tassels and fringing. That of the Ludovisi Hermaphrodite is relatively crude. The end of its base is lacking, apparently as a result of difficulties with the casting, and it is evident that the founder struggled with pouring the molten alloy evenly into the moulds as he had to patch and plug flaws across the body. Since leaving the ‘Kunstpalast’ museum in Bad Ems in Germany in 1961, these defects have become more apparent: the bronze has been used as a garden sculpture and the original dark, shiny, probably lacquered, surface lost. In its place is a far more romantic ‘archaeological’ patina. The piece looks as though it might have been dredged from the sea, like the thrilling Dancing Satyr that opened the Royal Academy’s 2012 ‘Bronze’ exhibition.

A bronze reclining figure of the Hermaphrodite (probably mid 17th century), Italy. Cast from the antique marble restored by Ippolito Buzzi in 1621-23. Christie’s. Estimate £200,000-300,000

It certainly convinced its owners, who believed it was an antiquity and insisted on a thermoluminescence test, the results of which suggest that it was made less than 150 years ago. (These tests are not invariably reliable, and Christie’s notes several factors that suggest a 17th-century production date). As a consequence, says Christie’s head of sculpture Donald Johnston, the estimate has been significantly reduced, and stands at £200,000–£300,000. What this self-evidently early and hugely resonant piece will achieve is quite a different matter. Such rare, full-size bronze casts of what were then the most celebrated works of art in the world – and which inspired some of the greatest art in the world – were hugely difficult and expensive to make. They were the province of kings – not least given the diplomacy required for the permissions to make such copies. Given all this, it is extraordinary to note that when the American artist Barry X Ball offered his Sleeping Hermaphrodite at Christie’s New York in May this year – a piece made by digitally scanning the Louvre sculpture and cutting it from a single block of Belgian black marble with the aid of a computer-guided carving machine (2008–10) – it should have come with an estimate of $500,000–$800,000.

Visit Apollo Collector Services for the best information and advice about managing an art collection.