Tucked round the side of Buckingham Palace is the Queen’s Gallery, the place to find some of the best conceived, researched and displayed exhibitions in London. It surely helps that curators select their pieces from the Royal Collection, which is held in trust by the sovereign for her successors and the nation. It is one of the world’s largest private art holdings, and one of the last great European collections remaining intact. This summer, in a rare departure from the gallery’s usual Old Masters focus, two concurrent shows reveal for the first time the quality and range of South Asian art in the Royal Collection. The pieces were not stolen or war booty; they were mostly diplomatic gifts presented through the centuries. Though not large, this collection is one of the world’s finest. Yet it’s mostly been in storage at Windsor Castle, and perceived to be inaccessible by the public.

This is all set to change. For the larger show, ‘Four Centuries of South Asian Paintings and Manuscripts’, Emily Hannam – the first curator focusing on its Islamic and South Asian holdings to be appointed at the Royal Collection – has selected 150 drawings, paintings and manuscripts. Many pieces go on public view for the first time, having undergone conservation in advance of the exhibition at Windsor. The aim is to draw attention to the collection, and encourage the curious to come and study it at Windsor.

The Earth from a series depicting the Bhagavata Purana (c. 1775–90), Nainsukh family workshop, Parahi. Royal Collection Trust; © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

Perhaps the most intriguing revelation is a group of 16 paintings made in the celebrated family workshop of the painter Nainsukh in around 1775–90. They illustrate a core Hindu text, the Bhagavata Purana, thought to have been written between the sixth and tenth centuries. It promotes bhakti (devotion) to the god Vishnu as the route to self-knowledge. A painting called ‘The Earth’, which illustrates the flood narrative common to most religions, depicts the earth floating on the ocean in all its verdant glory – for inspiration, the artists looked out at the Pahari hills and valleys of the Lower Himalayas where they lived, still a beautiful forested area of India today. Another, telling the story of Vishnu transforming himself into the man-lion Narasimha to save the world from a wicked demon, uses a jewel-bright palette of azure, mauve, turmeric yellow and orange to create a surreal, emotionally charged scene that blends realism with complex patterning and wild action set within a flat architectural setting.

Shah Jahan receives his three eldest sons and Asaf Khan during his accession ceremonies from the Padshahnama manuscript (detail; c. 1630–40), Bichitr and Ramdas, Mughal. Royal Collection Trust; © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

Among the star exhibits of the many excellent Mughal paintings and drawings are half a dozen pristine large paintings from one volume of the greatest known Mughal manuscript, the Padshahnama (Book of Emperors). It was made for the emperor Shah Jahan – who built the Taj Mahal – in 1656–57 as a deluxe piece of propaganda celebrating his reign and dynasty. During its creation, the emperor would hold daily meetings with the artists to discuss the paintings, which were packed with visual metaphors of imperial power. The book’s author deftly refers to it as ‘an adorned text, the description of which fills the listener’s dress with jewels’. This is visually encapsulated in the painting of Shah Jahan receiving his three sons and chief minister Asaf Khan at court during his accession ceremony – it was Khan whose political skills ensured Shah Jahan won the power struggle after his father Jahangir’s death. More than a century later, in 1798, this precious manuscript that had made its way to the Nawab of Awadh’s renowned library at Lucknow (later mostly destroyed by the British during the upheavals of 1857) was presented to the bibliophile and governor-general, Lord Teignmouth, to be given to fellow bibliophile George III. It has been kept safe ever since. The other two volumes known to have existed are lost.

The second show at the Queen’s Gallery is ‘A Prince’s Tour of India 1875–6’. It places the spotlight on one of the most elaborate instances of royal travel and royal gift-giving ever undertaken: Albert Edward, Prince of Wales’s four-month-long diplomatic progress to all corners of India, where he travelled some 16,000 kilometres by land and sea and was greeted by more than 90 rulers. In Madras, Calcutta, Bombay and Banaras – as those cities were then called – and across the rest of the country, the prince was given more than 2,000 exquisitely crafted diplomatic gifts showing off local skills. British representatives in India had been instructed to persuade the naturally generous maharajas that small was beautiful. Some gifts were more useful than others. Among the swords, shields and sceptres, opium boxes and turban ornaments, the prince received handy perfume holders and boxes. Perhaps the present that most successfully combined ingenuity, luxury and practicality – and also served as a souvenir – was presented by the Maharaja of Benares (now Varanasi): an inkstand in the form of the maharaja’s own peacock-shaped state barge, the one in which the Prince of Wales processed up the Ganga with his host at dusk on 5 January 1876.

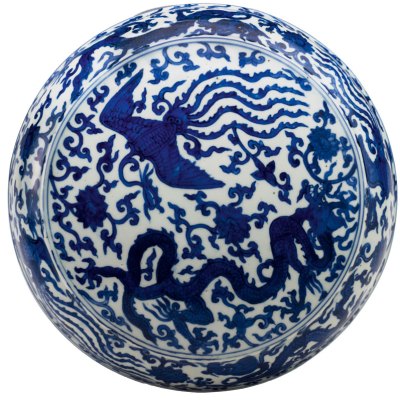

Peacock inkstand (c. 1970–75), Jaipur. Royal Collection Trust; © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

The prince was rigorously prepared for his trip by his mother Queen Victoria, with a reading list and curator-led visits to the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A) and the India Museum. This sharpened his eyes to Indian style and craftsmanship. Immediately on his return he decided to put the gifts on tour to inspire Western craftsmen. The exhibition travelled to eight cities in Britain, and to Paris and Copenhagen. It was so popular that it inspired pioneering late opening hours and museum stores – York’s was called an ‘Oriental Bazaar’. More than two and a half million people saw the exhibition. Then it all went into store for 130 years. Today, curator Kajal Meghani’s selection retells this story. She believes these delicate objects will be an inspiration to contemporary artists. It is a nice coda that today’s Prince of Wales founded the Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts in 2005 to encourage traditional skills in the UK and 20 countries around the world.

‘Splendours of the Subcontinent: Four Centuries of South Asian Paintings and Manuscripts’ and ‘A Prince’s Tour of India 1875–6’ are at the Queen’s Gallery, London, until 14 October.