When the time comes, newly reopened museums would be well advised to equip gallery assistants with smelling salts. Soft seats should be placed near paintings and sculptures. And visitors: be careful not to look too hard – at least, not until you have reaccustomed yourselves to being in the presence of a work of art. Glance, don’t stare. Check its image on your phone. And when you do raise your eyes for a really good look, watch out for the following symptoms: feelings of anxiety, alienation, disorientation or euphoria; a racing heart; the sensation of rising panic. If you experience any of these, you may be suffering from Stendhal syndrome.

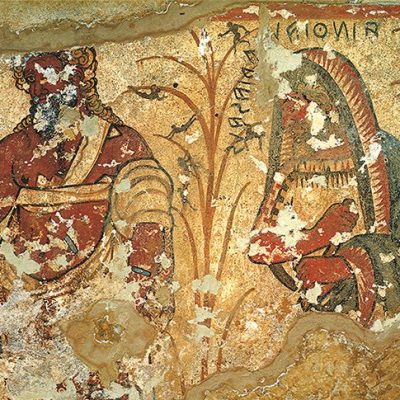

Identified as a phenomenon in 1989 by the Italian psychiatrist Graziella Magherini, the syndrome was named after an episode recorded in 1817 by the French novelist Stendhal when travelling around Italy. Newly arrived in Florence, he headed straight for Santa Croce where, contemplating the tombs of Michelangelo, Machiavelli and Galileo, he felt overwhelmed by what he described as a ‘tide of emotion’ that ‘flowed so deep that it scarce was to be distinguished from religious awe’. He asked a monk to unlock the Niccolini Chapel for him, and once inside he perched on a hassock and rested the back of his head on a desk in order to gaze up at the fresco of sibyls painted by Baldassare Franceschini in the 1650s. His soul, he recalled, ‘affected by the very notion of being in Florence, and by the proximity of those great men whose tombs [he] had just beheld, was already in a state of trance’ and he abandoned himself to ‘the contemplation of sublime beauty’. As he gazed, Stendhal’s experience grew more vivid still:

I could, as it were, feel the stuff of it beneath my fingertips. I had attained to that supreme degree of sensibility where the divine intimations of art merge with the impassioned sensuality of emotion. As I emerged from the porch of Santa Croce, I was seized with a fierce palpitation of the heart… the well-spring of life was dried up within me, and I walked in constant fear of falling to the ground. [Stendhal, Rome, Naples and Florence, trans. Richard N. Coe]

If this extreme reaction to beauty and historical atmosphere were going to happen to anyone, it was going to happen to Stendhal, touring Europe at the height of the Romantic movement with Goethe’s novel The Sorrows of Young Werther in his luggage. It was an era in which powerful emotions were cultivated and savoured. Remarkably similar psychosomatic experiences, however, have been recorded in more recent times: throughout the 1970s and ’80s Magherini became aware of the large numbers of tourists presenting themselves at the Santa Maria Nuova hospital in Florence complaining of dizzy spells and feelings of disorientation brought on by seeing paintings or sculpture they knew well from reproduction in books. An encounter with a Botticelli, a Raphael or a Michelangelo in the flesh – so familiar, yet uncannily strange – proved all too often to be an uncomfortable or even traumatic experience. As recently as 2018 a visitor to the Uffizi suffered a heart attack in front of The Birth of Venus.

Magherini noticed that a crisis of identity was experienced by most patients presenting with Stendhal syndrome. She describes the case of a young Czech painter, Kamil, who had hitchhiked from Prague to Italy: ‘when he went to see Masaccio’s work in the Cappella Brancacci, upon exiting he had an experience that was at once aesthetic and ecstatic, a feeling he was exiting from himself, dissolving away. He collapsed on the steps.’ In each case it was as though an encounter with the real thing made the spectator feel correspondingly less real.

Stendhal syndrome tends to strike in Florence because of the city’s sheer density of exceptional works of art and its profound historical significance. Elsewhere there are many galleries that even now I suspect most of us would be able to endure with unruffled composure. But what effect have museum closures and enhanced digital experiences – each more innovative than the last – had on our capacity to experience great art in the wild? What if our faculties of perception have grown pale, flabby and vulnerable? When we come face to face with oil paint, marble and sculpted wood again, will we find them bristling with beauty and emitting a dangerous aura of authenticity? We must be on our guard.

On the other hand, surely it would be equally strange to remain impassive and unemotional before works of great beauty, depth and humanity. ‘The uneasy silence of a man faced by a work of art,’ Lucian Freud once wrote, ‘is unlike any other. What do I ask of a painting? I ask it to astonish, disturb, seduce, convince.’ It is that mysterious, visceral exchange that many of us have been missing. Worth risking it, I’d say.