From the May 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Towards the end of Stephen Shore’s Modern Instances, the photographer describes meeting Ansel Adams at a dinner party in 1976. Unbeknownst to Shore, Adams had already seen Shore’s debut exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, which had opened in October that year. Adams secretly commended Shore’s work, rendered in colour with an ultra-sharp 10 x 8 inch camera, to the publisher Tim Hill, who would end up producing Shore’s first monograph, the still essential Uncommon Places (1982). Through these projects and others, Shore would quickly emerge as a master of the American vernacular, but before that night he and Adams had never met. As the evening wore on and Adams let down his guard (Shore counted six tall glasses of vodka passing Adams’s lips), he turned to Shore and confessed: ‘I had a creative hot streak in the ’40s and since then I’ve been potboiling.’

Whether Adams’s self-criticism was justified or not, Shore resolved at that moment never to fall into the same trap: ‘Whenever I found myself copying myself, I would give myself a new challenge.’ Now 74, the same age as Adams was when they met, he has produced evidence of that pledge in Modern Instances – a window into Shore’s restless monkey mind.

As the subtitle suggests, the book is less a treatise than a collection of philosophical ruminations, anecdotes, and literary and musicological vignettes, combined with selected imagery. The book’s design, which resembles a diary or field journal, underlines his intentions. Organised into chapters ranging from ‘The Evolution of Ignorance’ to ‘Visions from Antiquity’, it progresses through a series of apparent non sequiturs from the intimate to the theoretical.

The surprise for those familiar with Shore’s photography will likely be his obeisance to the Old Masters. One might expect modern and contemporary luminaries such as Walker Evans, Anselm Kiefer and Ed Ruscha to appear, and they do here and there, but the reader is much more likely to encounter the likes of Michelangelo, Fra Angelico or Andrea del Sarto. Shore also offers etchings by Rembrandt and Annibale Carracci, as well as two engraved plates from Blake’s Illustrations to the Book of Job. ‘I recall a time in my early twenties when I frequently returned to a group of pictures, mostly works on paper, and mostly in books,’ he explains. ‘And, if truth be told, there were occasions when I visited them after dropping acid.’

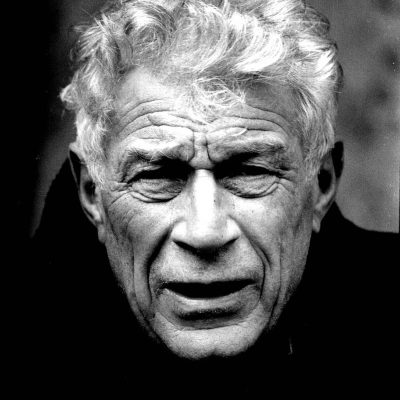

The eclectic mix of word and image calls to mind critic John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (1972) and indeed Berger makes a cameo, albeit briefly, as his experience of brain/body dissociation while riding a motorcycle is mentioned in the book’s weightiest section, an email exchange with the British photographer George Miles. Nevertheless, Modern Instances bears the stamp of Berger less than that of W.G. Sebald, whose playful and poignant juxtapositions of seemingly unassuming imagery and tightly-wrought prose are more than the sum of their parts.

For example, Shore repeatedly mentions his friendship with the late John Szarkowski, MoMA’s director of photography from 1962–91. He notes with interest the curator’s late-life fixation with growing apples on his farm in upstate New York, to the extent that he would describe himself publicly not as an art historian or curator, but as ‘an amateur pomologist’. (Coincidentally, Sebald’s English-language translator Michael Hamburger had a similar preoccupation with apples – as can be seen in Tacita Dean’s mesmerising film about him.) Later in the book Shore returns to the theme, inserting a 40th anniversary photograph of himself with his wife Ginger Shore, posed in an orchard laden with ripe apples.

Modern Instances teases many such delightful pathways. It is, ultimately, an act of curation – a visual and written art gallery with all the rhythm, push and pull of a great exhibition. At the same time, it is an extended metaphor for Shore’s life’s work and indeed for photography itself, complete with advances, reassessments, and occasional cul-de-sacs. There is seldom a straight line from A to B; nevertheless, Shore reminds us (as he has done throughout his career) that no matter what happens we must observe closely and pay attention. ‘One of the repeated themes in my work,’ he writes, ‘is the idea of experiencing the everyday world with attention,’ including, he cautions, attention to the act of seeing itself.

As a practical manifestation of a distinctive artistic philosophy, this book represents Shore very well. However, Modern Instances contains little in the way of conventional biography. Shore’s three years frequenting Warhol’s Factory, for example, receive only three pages towards the end; he paints Warhol as a vaguely melancholy figure, with ‘a distanced delight in contemporary culture’, which Shore shared. Likewise, Shore’s extraordinary engagement with Instagram and his attempts to make sense of the onslaught of contemporary social media imagery – surely one of his most momentous bodies of work – is scarcely discussed. Fair enough. The book does not claim to trace an artistic lineage. What would be the point? As Szarkowski would have told us, apples do not grow true to seed.

‘Modern Instances: The Craft of Photography – A Memoir’ by Stephen Shore is published by MACK.

From the May 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.