For the past half-century, the American artist Michelle Stuart has worked in – and with materials drawn from – the natural landscape. At the centre of her work, Stuart tells Apollo, is the connection between human life and the mysteries of the universe.

The works in this exhibition [‘Michelle Stuart: The Nature of Time’ at Alison Jacques, London] date from the late 1960s to the present day. How does it feel to see all this work in one space?

The first word that came to my mind is gratifying, because there’s a connecting line. I am there, and the mystery that I wanted to express, or I couldn’t help expressing, is there: the confrontation of our outside being and our inside being. It’s not that easy to inject these ideas subtly into a person’s imagination: the mystery of the strata, of time, and the mystery of the cycles.

Do you see your earlier works differently now from when you first made them?

That’s an interesting question. Well, when you look back you’re including other peoples’ comments about the work – it becomes an accumulation of everybody’s ideas and you can’t escape that. The first really good criticism of my work was by the English critic Lawrence Alloway. He came to my studio – I didn’t invite him, he called up and said he’d like to do a studio visit because he’d seen some pieces in a show – while I was preparing for a show at Max Hutchinson’s gallery in the early ’70s. He saw my scrolls, and pointed at one that was slightly different to the scrolls in this show [at Alison Jacques] and asked if I was including it. I said I hadn’t decided yet and he said ‘don’t’. I asked why and he said it was another path. I listened to him and he was right. I got along with him but a lot of people didn’t; he was a difficult man, very upfront.

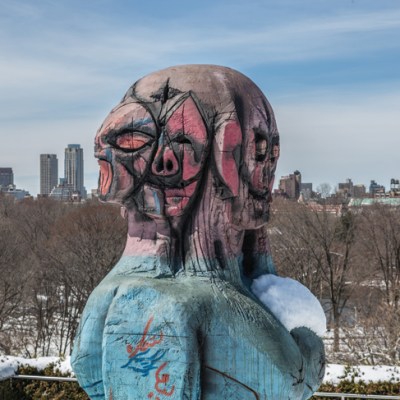

#6 Kingston (1973), Michelle Stuart. Courtesy Alison Jacques Gallery, London; © Michelle Stuart

One of the contexts in which your work has long been placed is the birth of land art. Did you feel you were part of this movement at the time?

You know, I’ve never wanted to be a part of anything. Peripherally I was, because I did outdoor works, like the one in Oregon [Stone Alignments/Solstice Cairns (1979)]. I love that piece. It was a wonderful experience actually – with all the outdoor pieces I did, I hope they were as good for the viewers as they were for me, I really liked making them. They weren’t big productions like the guys were doing, they didn’t need great big tractors and things like that. I found that somehow you can say things without becoming a developer!

With Stone Alignments/Solstice Cairns, I had the perfect site chosen and literally the day before I went from New York I got a call saying I couldn’t use the site because there were going to be all these really fragile flowers. I was sent some photos and I found another site, this plateau where I ended up doing the piece, it was a lot rockier, which was perfectly okay. One assistant and I built this whole piece. There were rattlesnakes all over the plateau, but they were very circumspect. We made a deal and we didn’t put a rock or a boulder over a rattlesnake hole. They never bothered us; it was perfect. A funny thing happened: there was a bird’s nest which had appeared on one of the rocks, and the day of the opening the eggs opened, and we were so afraid that the rattlesnakes were going to eat them and so all day we were watching the bird’s nest with the little birds. They fared well, they did okay. It’s funny remembering all this: 1979 was a long time ago. I’ve been back but it’s virtually disappeared – it’s still there but it’s a kind of ruin.

Sacred Solstice Alignment (1981, printed in 2014), Michelle Stuart. Courtesy Alison Jacques Gallery, London; © Michelle Stuart

The term ‘earth work’, often used to describe land art, is also the term given to archaeological sites believed to have been built to express cosmological ideas. These appear frequently in your work – in Sacred Solstice Alignment (1981), for instance. What’s the link between your work and these sites?

That’s difficult to answer: I don’t want to just throw something out there. But I do relate profoundly to these sites – it’s very surprising to me that not everybody does. Some of the sites do express abstract cosmological ideas, but they were also rooted in farming practices. My own work is a kind of interpretation of these structures. These days most people don’t have time to know or care about these things, they just have to make a living but luckily that’s my living: to imagine, to revive and make visible this human connection with the universe.

Chatham Boat (pink flag) 2017 (2017), Michelle Stuart. Courtesy Alison Jacques Gallery, London; © Michelle Stuart

Connection, or contact, is made perhaps most literal in your scrolls, which involve frottage with graphite on sheets pressed against the earth. Some people have taken this technique as a reference to Surrealism. Is it?

It isn’t about Surrealism. Max Ernst wasn’t doing the same thing as me at all – he was rubbing to find figures like birds and to tell a story. I may be telling a story but it’s not the same story. The funny part of it is that I didn’t know Ernst’s rubbings at that point at all. Looking at my ones in retrospect, I think about how obsessive they are.

Finally, I want to ask about a more recent work, Chatham Boat (pink flag) (2017). What was the inspiration behind it?

I do boats, for myself – I don’t usually show them. It’s a hobby of mine. Once in a while people wander in and see one and buy one, or ask to put it in a show, like Alison [Jacques] has done. I love boats; I travelled here on the Mary 2. It’s big but it’s still a boat.

‘Michelle Stuart: The Nature of Time’ is at Alison Jacques, London, until 28 July.