‘Show Sunday’, the day on which Victorian artists opened up their studios to display the works of art they were about to dispatch to the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition, was part of the London Season. In 1881, however, the Art Journal noted that it was attracting the wrong kind of visitor: people now came ‘to see the studio, and if possible the live artists, rather than the pictures’. The press itself was partly responsible for this, the New Journalism of the 1880s creating a cult of personality by running photogravure-illustrated profiles of famous people. An article on Frederic Leighton published in the Strand Magazine in 1892 had two illustrations of the artist, ten of the interior of his spectacular home and studio, but only four of his paintings. Artists nevertheless recognised that studio visits, whether from the press or the public, were not only good for sales but allowed them ‘to curate exhibitions of their own work’ rather than have it hung any old how among that of other artists on the crowded walls of galleries.

‘Show Sunday’, the day on which Victorian artists opened up their studios to display the works of art they were about to dispatch to the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition, was part of the London Season. In 1881, however, the Art Journal noted that it was attracting the wrong kind of visitor: people now came ‘to see the studio, and if possible the live artists, rather than the pictures’. The press itself was partly responsible for this, the New Journalism of the 1880s creating a cult of personality by running photogravure-illustrated profiles of famous people. An article on Frederic Leighton published in the Strand Magazine in 1892 had two illustrations of the artist, ten of the interior of his spectacular home and studio, but only four of his paintings. Artists nevertheless recognised that studio visits, whether from the press or the public, were not only good for sales but allowed them ‘to curate exhibitions of their own work’ rather than have it hung any old how among that of other artists on the crowded walls of galleries.

From being ‘a box wherein miserable painters hide themselves’, as Augustus John put it, the studio evolved into a space where work was displayed as well as created. Artists started to commission architects to design purpose-built homes and studios, buildings that not only provided them with ideal places to live and work, but also reflected their aesthetic ideas and personae.

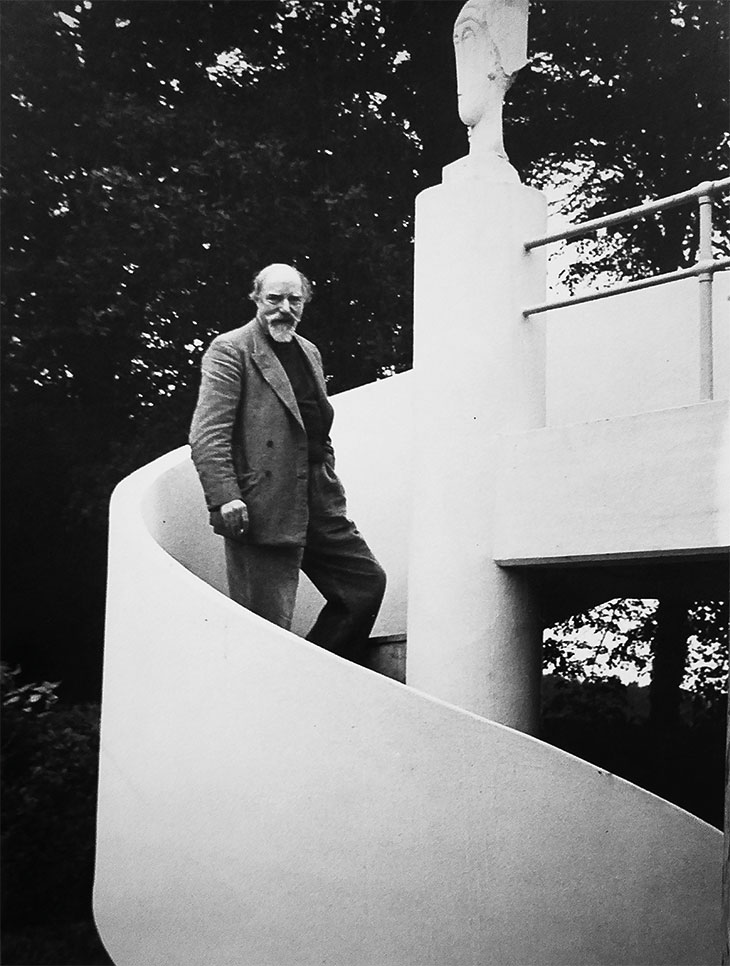

Augustus John outside his studio designed by Christopher Nicholson (photographed in 1937 by Howard Coster). Courtesy Lund Humphries

In this generously illustrated book Louise Campbell looks at 13 examples of artists’ houses and studios, from Limnerslease, the house G.F. and Mary Watts had built in 1891, to Brackenfell, the studio Leslie Martin and Sadie Speight designed for Alastair Morton in 1938. The artists are well chosen, with a wide range of working methods. They also displayed varying degrees of collaboration and co-operation with their chosen architects. William Reid Dick had provided numerous carved figures, panels and friezes for buildings designed by Thomas Tait before selecting the architect to create a studio for him in St John’s Wood. His fellow sculptor Dora Gordine had a less happy experience when she commissioned Godfrey Samuel of Tecton to design a house and studio for her in Highgate. The notoriously intransigent Samuel did not respond well to Gordine’s comments and suggestions, and the scheme was abandoned with little regret when the owner of the site, having seen the plans, withdrew his permission to build. Fortunately Gordine found another site in Kingston Vale and an architect happy to take on the role of general contractor, leaving most of the detailed design to his client. She worked from the inside out, first creating the interior spaces in which to make and display her sculptures, but the result (completed in 1936) was an imposing building that owed a good deal to John Soane, who was being favourably reappraised at the time, while remaining very much of its period.

F.E. McWilliam’s Studio House was also built in the 1930s, in the grounds of a recently demolished 18th-century manor house in the London suburb of New Malden. The semi-rural site, planted with birches and willows, appealed to McWilliam, who was interested in the relationship between sculpture, architecture and landscape and had no near neighbours to complain about the noise of his power-drills. The original plan to use the building as an exhibition space failed to materialise, New Malden proving too far away from London to attract visitors; but McWilliam learned from profiles of artists in the French press that skilful black-and-white photography could be used to publicise his work, since it was particularly effective in showing off the forms and planes of sculpture. He was able to curate his own exhibitions – albeit virtual ones – rather in the way Victorian artists had, sometimes using collage or panorama. These photographs further demonstrated that the studio was ‘the proper place to look at sculpture’, an environment that acknowledged ‘the sculptor as the creator of his own world, not the decorator of someone else’s’.

William Orpen in his studio (photographed in 1927 by Howard Coster). National Portrait Gallery, London. Courtesy Lund Humphries

Photographs of artists’ homes also suggested to potential buyers how works could look in situ, while Gluck is a good example of someone who befriended and collaborated with architects, creating paintings for specific rooms. Her feel for architecture was apparent at an exhibition of her work at the Fine Arts Society in 1932, where the walls were ‘divided into bays by means of a raised plinth and pilasters’ and the pictures hung in stepped frames that made them seem part of the overall design. Unsurprisingly, Gluck was closely involved in the design of the modern studio created for her by Edward Maufe in the garden of her Georgian home in Hampstead. Maufe had previously helped transform the house into ‘a fashionable synthesis of the Georgian and the modern’, painting its panelled walls white, the better to show off Gluck’s flower paintings, which Homes and Gardens found ‘as perfectly in keeping with the prevailing style of modern decoration as those stylised Dutch flowerpieces, brilliantly coloured and heavily framed, with the richly decorated and strongly coloured interiors they were intended to adorn’.

As someone whose whole style was intended to convey her artistic ‘self’, Gluck is perfectly suited to Campbell’s purposes, and there are equally illuminating investigations of William Orpen’s ‘swagger studio’ in South Bolton Gardens, Ben and Winifred Nicholson at Banks Head in Cumberland, Eileen Agar in Earl’s Court, and Barbara Hepworth and John Skeaping at the Mall Studios, Belsize Park. Not every studio was a success, however. Augustus John, rather in the spirit in which he had traded in his gypsy caravan for a sports car, commissioned Ben Nicholson’s brother Christopher to create a studio in the International Style in the grounds of his 18th-century country house. In the event, this old wine did not like being put in a new bottle and John more or less abandoned Nicholson’s elegant studio for the ‘decaying homeliness’ of an old building in the orchard.

Studio Lives: Architect, Art and Artist in 20th-Century Britain by Louise Campbell is published by Lund Humphries.

From the March 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.