From the July/August 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘Nothing strikes the eye nor signals the magnificence of the king better than a well-adorned ship.’ This assertion by Louis XIV’s minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert reflects the king’s ambition to expand France’s navy at the outset of his personal reign. Meredith Martin and Gillian Weiss’s fascinating new study reveals that the model of absolute monarchy who devoted his boundless energy to warfare on land also took a keen interest in his navy – for which he had more than 40 galleys built, all crewed by convicts and enslaved Turks. The Sun King at Sea investigates this largely overlooked chapter in the history of the Bourbon monarchy, discussing it in the context of the maritime art it inspired, as exemplified by paintings, prints, medals, sculptures and ship designs.

Moving their attention away from the traditional centres of power, Paris and Versailles, to the port of Marseille, Martin and Weiss chronicle the miserable fate of those forced to row the royal fleet. The book shows how the navy was intended to cement Louis XIV’s image as the ‘most Christian king’. This ambition is encapsulated in The Reestablishment of Navigation, 1663 (1678–84), one of the many allegorical portraits of the king churned out by Charles Le Brun’s workshop to make up the magniloquent imagery of the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. It depicts an enthroned Louis XIV in Roman guise and holding a triton; at his feet are three turban-wearing captives. According to the authors, this scene is to be understood as an illustration of the king’s ‘ability to cleanse the Mediterranean of an enemy faith and dominate the sea by enslaving Muslims’. Representations of chained captives became the hallmark of an iconography boasting the maritime power of the French state; it quickly entered the repertoire of decorative schemes ranging from sculptural facades to tapestry borders. In Le Brun’s painting and in many other works, the depiction of chained and uncomfortably twisted torsos exudes a clear message of domination and objectification.

Moving their attention away from the traditional centres of power, Paris and Versailles, to the port of Marseille, Martin and Weiss chronicle the miserable fate of those forced to row the royal fleet. The book shows how the navy was intended to cement Louis XIV’s image as the ‘most Christian king’. This ambition is encapsulated in The Reestablishment of Navigation, 1663 (1678–84), one of the many allegorical portraits of the king churned out by Charles Le Brun’s workshop to make up the magniloquent imagery of the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. It depicts an enthroned Louis XIV in Roman guise and holding a triton; at his feet are three turban-wearing captives. According to the authors, this scene is to be understood as an illustration of the king’s ‘ability to cleanse the Mediterranean of an enemy faith and dominate the sea by enslaving Muslims’. Representations of chained captives became the hallmark of an iconography boasting the maritime power of the French state; it quickly entered the repertoire of decorative schemes ranging from sculptural facades to tapestry borders. In Le Brun’s painting and in many other works, the depiction of chained and uncomfortably twisted torsos exudes a clear message of domination and objectification.

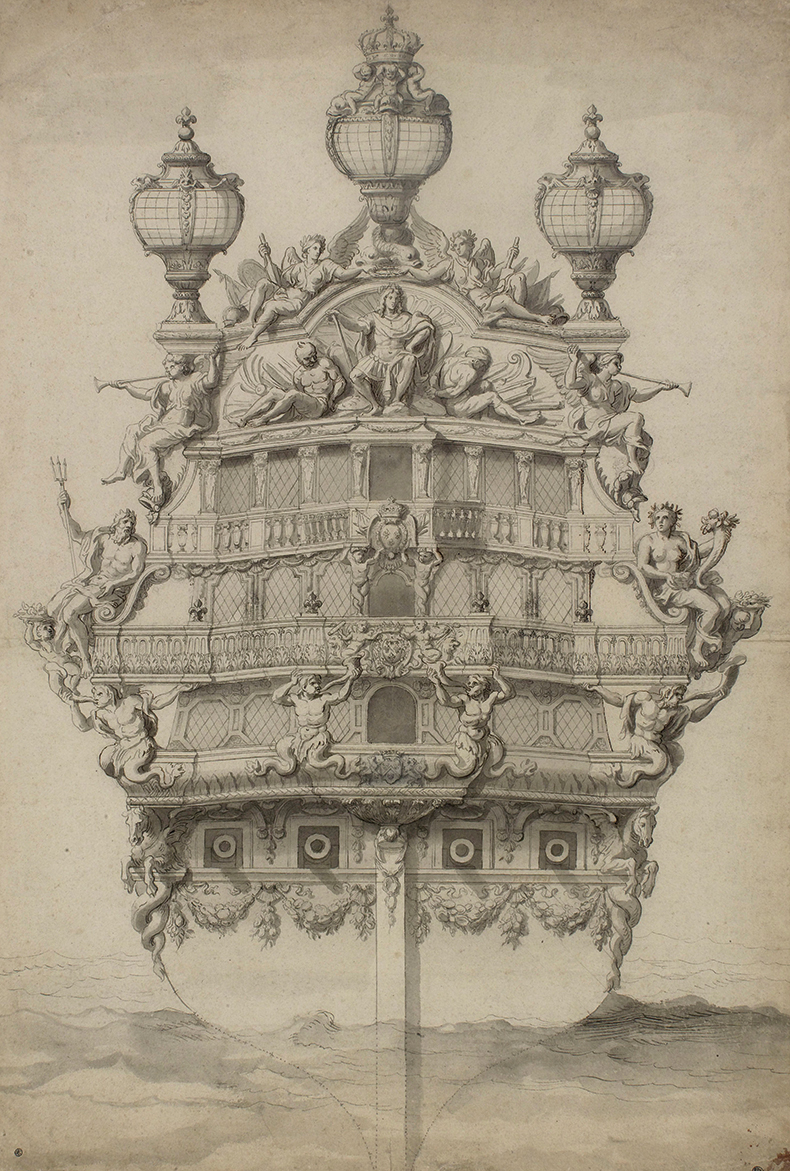

Another such example can be found on the grand elevation of the Royal Louis in a drawing ascribed to Le Brun’s workshop. The design illustrates the elaborate sculptural ornamentation the king’s principal painter had conceived for the most significant addition to the fleet. Colbert had tasked Le Brun to come up with celebratory imagery including personifications of Fame and depictions of sirens, the whole presided over by the Sun King – presented once again as a Roman conqueror with chained captives at his feet. François Girardon, who was working on his group of Apollo served by six nymphs at the time, was sent to Toulon to oversee the realisation of Le Brun’s design, which took 40 artisans more than a year to carry out. At the same time, Colbert had two enslaved Turks sent from Toulon to Paris to serve as life models at the Royal Academy, which he had just set up.

Many of the works discussed by Martin and Weiss have been hiding in plain site and are being examined here properly for the first time. One of the most intriguing documents in The Sun King at Sea is the Album des Galères (c. 1680), a volume of 25 ink-and-wash elevations attributed to the gentleman-soldier Jean-Antoine, marquis de Barras de la Penne, which explain the building and fitting out of a galley. Plate XXII renders with chilling precision the arrangement of enslaved rowers in the belly of the vessel. It recalls the now widely known diagram of the English slave ship Brookes, which gave visible form to John Newton’s description of human cargo being tightly arranged like ‘books upon a shelf’.

In their examination of the Album des Galères, Meredith and Weiss are particularly attentive to the overall absence of text and the rhetorical significance of the decorative yet empty cartouches for each plate; how the captions would have read remains unknown. Plate XXIII illustrates the elevation of a galley’s bow and stern. Its large, symmetrical cartouche shows two French sailors whipping Turks, entwined in ornamentations of acanthus leaves, ropes and harpoons. The formulaic manner in which scenes of violence are included into such purely decorative schemes, one might argue, emphasises the ideological brutality of Louis XIV’s regime. Writings about the monarch, and especially his patronage of the arts, can largely be divided up into two categories: the first is predominantly immersed in the seductive qualities of louis-quatorze art and architecture and does not concern itself with the inhumanity of the political system that enabled its creation; the other is so focused on the violent realities of the 17th century that any appreciation of its visual output becomes a guilty endeavour. The contribution of Martin and Weiss is an important step in addressing a difficult subject in a forthright yet analytical manner. The Sun King at Sea presents original research in abundance with an apparatus of extensive endnotes; a comprehensive bibliography at the end of the book (which it lacks) would have been a helpful resource for scholars aiming to explore the subject further.

Drawing of the stern of the Royal Louis (c. 1680), studio of Charles Le Brun. École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris. © Beaux-Arts de Paris, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Dist. Photo: Scala, Florence

The authors situate the publication of their book firmly in the context of today’s discourse about social justice in the United States and Europe, concluding with a note that the treatment of enslaved Muslims by the regime of Louis XIV should receive the same level of scholarly attention as the Huguenots persecuted after the Revocation of the Edict de Nantes. If the language and tone of the book appears less emotionally charged than a comparable study of slave ownership in the early days of the United States, then this is because the political system behind it – absolute monarchy – is long dissolved in most parts of the world and will appear foreign and distant to most readers. Martin and Weiss’s exploration of this challenging material, and the language they employ, is commendable.

The Sun King at Sea: Maritime Art and Galley Slavery in Louis XIV’s France by Meredith Martin and Gillian Weiss is published by the Getty Research Institute.

From the July/August 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.