From the September issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

The centenary of Alberto Burri’s birth is being marked by exhibitions and events, which reveal the tensions between local and international influences beneath the artist’s stitched, burnt and cracked surfaces

It is 100 years since Alberto Burri (1915–95) was born in Città di Castello, Umbria. This area of Italy, in and around the Valtiberina, was also the birthplace of Michelangelo, Raphael, Piero della Francesca and Luca Signorelli. Burri’s territorial pedigree, however, could not smooth his entry into the canon of modern Italian masters. In April 1959 the display of his Large Sack (1952) at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna prompted parliamentary questions.

Burri’s rise to prominence and his acceptance in Italy was partly prompted by the appreciation of his work in the United States. Burri became popular among American collectors and curators, and despite their apparent fragility, his works travelled well. In 1953, following successful solo exhibitions at the Frumkin Gallery in Chicago and the Stable Gallery in New York, Burri was included alongside Karel Appel and Pierre Soulages, among others, in James Johnson Sweeney’s ‘Younger European Painters’ at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Sweeney wrote the first monograph on Burri two years later, curated another touring exhibition in 1957–58, and acquired three works for the Guggenheim’s collection, including Composition (1953), exhibited at ‘Younger European Painters’.

The Guggenheim’s relationship with Burri will be celebrated in a major retrospective (9 October–6 January 2016), but the centenary events are coordinated by the Fondazione Burri in Città di Castello. In the last two decades of his life Burri bought back many of his works and curated two permanent displays, one in the Renaissance splendour of Palazzo Albizzini, the other in former tobacco drying sheds. Burri’s Umbrian base may fit with a provincial image of the artist, but his oeuvre, career and legacy reveal a tension between his Italian heritage and international reputation. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the centennial events, which in Italy focus on his connection with local Old Masters, and site-specific works, while the New York and London exhibitions make apparent his international relevance.

Large Sack (1952), Alberto Burri. Galleria nazionale d’arte moderna e contemporanea, Rome © Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, Citta di Castello/2015 Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Burri’s career as a painter began in the United States, in a Texas prisoner of war camp. He had initially trained as a doctor, and served as a medic during the Second World War, but took up art after being captured in Tunisia in 1943 and interned in Hereford, Texas. He returned to Italy in 1946, and presented his first solo show of landscapes and still lifes at Rome’s Galleria La Margherita the following year. After a trip to Paris he began trialling means of destroying the flatness of the picture plane, adding texture to surfaces to create his catrami (tars) and muffe (moulds), and armatures to canvases for the gobbi (hunchbacks).

Over half a century Burri experimented with different techniques and supports to create paintings almost without paintbrushes – smearing tar, stitching burlap, burning plastic, welding iron, drying a mix of paint and glue and carving celotex boards. He continued to subvert the flatness of two-dimensional media in his tactile prints, which will be displayed at Luxembourg & Dayan in New York (17 September–24 October 2015). For Burri ‘the material was nothing other than the equivalent of the paint’; it offered him an otherwise unachievable combination of colour and texture. His materials, like his palette, were increasingly dominated by red, white, and black. Many of his late works use black paint on celotex boards prepared to create geometric abstract forms devoid of colour. Burri had initially used celotex (a type of industrial insulation) as a support, before experimenting with it as a material; his other materials had often been discarded before he used them and possessed connotations that he downplayed.

One of the earliest and most famous of Burri series is the sacchi (sacks), which are particularly rich in significance. Some of the sacks were originally used to deliver American aid to Italy in the post-war period as part of the Marshall Plan. In SZ1 (1949) patches of the Stars and Stripes are visible and the Italian text reads ‘For European Recovery supplied by the United States of America’. Burri includes an AM-lire banknote, the Allied Military currency issued in Italy after the invasion of Sicily in 1943, in a 1952 Sack. Despite his insistence on silence, the burlap speaks of a particular moment of Italian (and Italian-American) history, a trend which continues throughout Burri’s career. His use of plastics, iron, vinavil (a polyvinyl acetate glue) and celotex reflects Italy’s increasing industrialisation. Even his legni (wooden pieces) use veneer, implying manufacture not nature.

Burri’s materials do not only find connections with modern Italy. The burlap of his sacks has been compared to the robes of St Francis of Assisi, another son of Umbria. In 1975 an exhibition of Burri’s works, including the large and intricately patched Large Sack (1957–58), was held at the Sacro Convento di San Francesco in Assisi, where the saint’s own mended and darned robes are still conserved. Burri’s use of gold, a material he applied to a variety of supports, has also been compared with the gold grounds of early Renaissance altarpieces. New research undertaken for the Guggenheim exhibition will show how well versed Burri was in the construction of painting, and his use of traditional layers of gesso, bole and gold. Burri’s keenness to compare his own use of gold to that of his artistic ancestors is evident in his donation of the series Gold and Black to the Galleria degli Uffizi in 1994.

The first two exhibitions in Italy marking the centenary also highlight Burri’s art-historical heritage. In Sansepolcro, ‘Rivisitazione: Burri incontra Piero della Francesca’ (31 October 2014–12 March 2015) brought four works spanning Burri’s career into dialogue with Piero’s Resurrection (c. 1458) at the Museo Civico. As the foundation’s director Bruno Corà has argued, the two artists share a balance of form and space, geometric tension and classicism.

While Burri’s works were displayed in a gallery adjacent to Piero’s, a direct comparison with the frescoes of Luca Signorelli was possible at a study day at the Oratorio di San Crescentino in Morra, also near Città di Castello. Again this encourages fresh interpretation of Burri’s deconstruction of painting, juxtaposing the simple geometry of a celotex to Signorelli’s compositions and the intricate cracks of a cretto to the aged surfaces of fresco. Burri’s donation of the money he won for the Premio Feltrinelli for graphic art in 1973 to the restoration of these frescoes is as much the subject of the accompanying exhibition (until 4 October 2015) as the opportunities for visual comparison.

The frescoes of the Valtiberina are site-specific, the works by Burri brought to them from the nearby Fondazione. Burri also created site-specific works, one of which is being completed and restored, prompting the re-examination of the cretti from a different angle. Burri’s Il Grande Cretto (1984–89) is a 85,000 sq m concrete shroud covering the ruins of the historic Sicilian town of Gibellina, destroyed by an earthquake in 1968. The cretti are often small for technical reasons, and so this larger-scale land-art version, with its pathways of cracks, emphasises how Burri extended his performative process to the viewer.

Alberto Burri’s ‘Il Grande Cretto’, made between 1984-89 in the old Italian city of Gibellina which was devastated by an earthquake in 1968. Photo: Gabriel Valentini, Wikimedia Commons

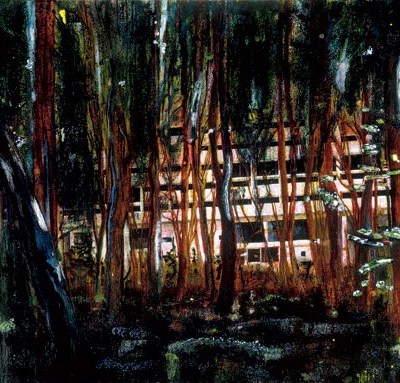

This is also the case in Milan, where Burri’s Continuous Theatre, an open-air stage originally erectedin Parco Sempione for the XV Triennale di Milano in 1973, has been reconstructed. The simple stage, with white and black flats at either end, takes as its backdrop the Torre Filarete of the Castello Sforzesco from one side and the Arco della Pace on the other. The council decided to demolish the stage in 1989, despite it being a rare sculptural work by Burri, and a popular public artwork. The element of chance here falls to the public rather than the artist (thus making a reconstruction possible); a work positioned with topographical precision becomes a world stage during Milan’s current universal exposition.

Burri’s life, like his art, was both local and international. Cesare Brandi called Burri’s 1975 exhibition in Assisi: ‘Not merely a provincial event, but the symbol of a strong tenacious attachment of he who through his works has become a citizen of the world.’ After his marriage to the American dancer Minsa Craig, Burri lived in Los Angeles for the winter months, and he travelled internationally. He was fundamentally a solitary artist, but maintained friendships with artists from Calder to Kienholz, and has been connected artistically to a range of contemporaries. The difficulty in defining Burri in terms of major trends in modernism has contributed to a reputation for provincialism, but he has been better described as ‘an artist of the periphery’.

In the context of modern Italian art, Burri was part of the short-lived Gruppo Origine in 1951 which opposed the decorative trend in abstract painting. It is more widely known as a bridge between the tactile polymaterial art of Futurist Enrico Prampolini and Arte Povera, particularly Jannis Kounellis, also known for his use of sacks, and Pino Pascali, a visitor to Burri’s studio who also worked with shaped canvases. Within European modernism, after the ‘Younger European Painters’ exhibition, Burri was linked to the abstraction of Art Informel, but the critic Carla Lonzi noted his Dada spirit as early as 1960. Burri’s performativity recalls many European contemporaries: his use of fire connected him to Yves Klein and the Zero Group; the photographs of him shooting a beer-can, and the subsequent exhibition of the can, link him to Niki de Saint-Phalle; and his desire to transform materials connects him to Joseph Beuys, who met Burri in Città di Castello in 1980.

Although Burri and Ben Nicholson were friends from the 1950s, and shared an interest in abstract geometric forms,Burri has received a comparative lack of attention in Britain. The Tate acquired Sacking and Red (1954) in 1965, and included him in the 2005 exhibition ‘Beyond Painting: Burri, Fontana, Manzoni’, but he was only granted his first UK retrospective at the Estorick Collection in 2012. His second will be held at the Mazzoleni Gallery, London, which will show the Turin gallerist’s extensive collection of Burri (2 October–30 November). This will be a rare opportunity to enjoy these paintings – which for their tactility, materiality and three-dimensionality must be seen ‘in the flesh’ – in the UK. The only other example of Burri’s work in a British public collection is in the Hunterian, Glasgow. The late black-and-gold piece was donated by the artist in 1993, the result of the artist’s relationship with the University of Glasgow’s then head of art history, Alan Tait. However, even this Scottish connection returns us to the importance of America in Burri’s career: Tait was Sweeney’s son-in-law.

Burri’s combination of performativity, abstraction and large scale invites parallels with American Abstract Expressionism. It may be action painting, but its creation of spaces between the viewer and the picture plane is at odds with the modernist rhetoric of flatness and emphasis on visuality. The ambiguities within Burri’s work becomes particularly evident in comparison with the generation of American artists who gained familiarity with his work in Rome, and through his American presence.

In 1953 Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly, on their famous Roman trip, apparently visited Burri’s studio. There Rauschenberg would have seen three 1952 works, Large Sack, Large White and Large Sack, which will be reunited for the Guggenheim exhibition. The American had already painted and exhibited his own series of White Paintings, but his break with two-dimensional painting occurred in Rome and was seen in his exhibition of feticci personali at the Galleria Obelisco, where Burri had previously exhibited. In dialogue with the American’s Neo-Dada ‘combines’ we are forced to reflect on the extent to which Burri transformed his ready-made materials.

The sculptor Lee Bontecou could also have seen Burri’s work in Rome in the 1950s while on a Fulbright scholarship. Interpretations of Bontecou’s wound-like reliefs are often feminist, while those of Burri’s are related to his medical training more readily than his sexuality. Despite Burri’s later protestations, Sweeney’s early interpretation of Burri’s surfaces as ‘human, bleeding flesh’ has stuck. Comparison with Bontecou, and the material experimentations, tactility, and bodily allusions of Eva Hesse – an artist who likely became familiar with Burri through his presence in New York – demands revision of the emphasis on medical analogies which Burri himself disliked.

The ambiguity in Burri’s oeuvre has arguably served his career well. The Guggenheim retrospective is titled ‘The Trauma of Painting’: to those seeking literal trauma Burri is, to use another of Sweeney’s phrases, ‘St Januarius of the Collage’, whose discarded materials become flesh and blood in the presence of the living; to those looking for a more figurative trauma, he deconstructs the flatness and purity of modernist painting. And yet, the difficulty in categorising Burri is also to blame for his reputation as a provincial artist. Peripheral, rather than provincial, Burri was a nomadic painter travelling between the cradles of the Italian Renaissance and the American avant-garde, creating interstitial spaces between figuration and abstraction, realism and modernism. The centennial events bring this ambiguity to the fore, and allow Burri to occupy an art-historical space as richly layered as the surfaces of his work.

‘Alberto Burri: The Trauma of Painting’ is at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, from 9 October–6 January 2016.