In the January 2016 issue of Apollo, the pioneering conceptual artist Susan Hiller (1940–2019) talked to Apollo about her interest in the supernatural, working in different materials, her commitment to feminism – and why role models are hard to find

‘What’s happened to the witch, the German puppet witch?’ Susan Hiller enquires of the waitress in the North West London bar that we’re sitting in, which she regularly frequents. Behind us every inch of the wall is filled with flea market paintings. Above us, shelves are casually piled with all manner of dusty bric-a-brac: bottles, trophies, ornaments, a Budweiser sign, and a stuffed owl. The witch is found. She’s hidden behind old saucepans, lamps and violins hanging from the ceiling. Hiller is an artist who has always had an eye for everyday objects and occurrences and an interest in the supernatural, subjects that before her, were rarely the focus of artworks – be it the ‘Rough Sea’ postcards she collected from the 1970s of British seaside towns, or the stories of UFO sightings she gathered and recorded for Witness (2000). So this seems an apt setting to look back over her 50-year career. ‘That sail boat wasn’t here last time,’ she says.

Hiller hates the word ‘retrospective’ but her current show (until 9 January), not far away at the Lisson’s two galleries, is close to being one. It contains new work but also reaches right back to the 1960s, when she abandoned a career in anthropology. It was during a lecture on African art that she made the decision to pursue her teenage dream of becoming an artist: ‘I committed myself to dealing with our culture,’ she tells me. Hiller moved from America to London after visiting the city and didn’t want to leave: ‘It was an astonishing place in the late ’60s and ’70s. It was the most open situation for all the arts. Different worlds were more interconnected. People came from all over because it was cheaper. It’s hard to believe now.’

While she works with ephemera as Pop artists did, and while the appearance of Hiller’s work may resemble her conceptual contemporaries and forbearers, her thinking has always been different. She calls her practice ‘paraconceptual’, her interest in the supernatural separating her from other artists of the time. In her Homage series, she has even looked back into art history, highlighting where artists have been inspired by the paranormal but have distanced themselves from it. Influenced by minimalism and conceptualism, she has always worked in series: ‘It’s more democratic, less hierarchical than a single thing that is elevated. Singularity is very old fashioned. Multiplicity is more compatible with the way we are. We’re surrounded by endless multiples.’

Hiller has also worked with many different media, from photography and ceramics to moving image, and she used sound before many other artists thought to. She likes it because it’s ghostly and intimate. ‘And it’s actually physical. The vibrations touch your ear. That makes it unique in a way.’ She continues: ‘Someone asked me the other day, “What made you think that you could use sound when no-one else was?” Well, I got permission from Kurt Schwitters, who was already dead.’ Working with so many different media hasn’t been without difficulties though: ‘People used to say to me, and it was a criticism, “Oh, you do so many different things.” Artists were trained to do the same thing over and over again and it was thought to be a lack of consistency if you didn’t do that. But I would say that I am very consistent. Possibly even more consistent than I’d like to be. I can’t help it. You can try and make every piece of work different but they’re always the same. The medium is often different. Or the formal approach is different. But we only have a limited amount of obsessions.’

I ask her how she chooses her medium. ‘It’s a question of matching the two together. The medium is selected because it’s appropriate to the subject matter,’ she says. ‘That’s the difference between the way I work and the way a lot of artists work. They make films. Or they use photography. I don’t work like that. I’ve had to learn so many different media because I’ve had to find ways that are suitable. But it does mean that I don’t produce work as quickly as some people do. It’s never boring. I don’t know what the next work will be.’

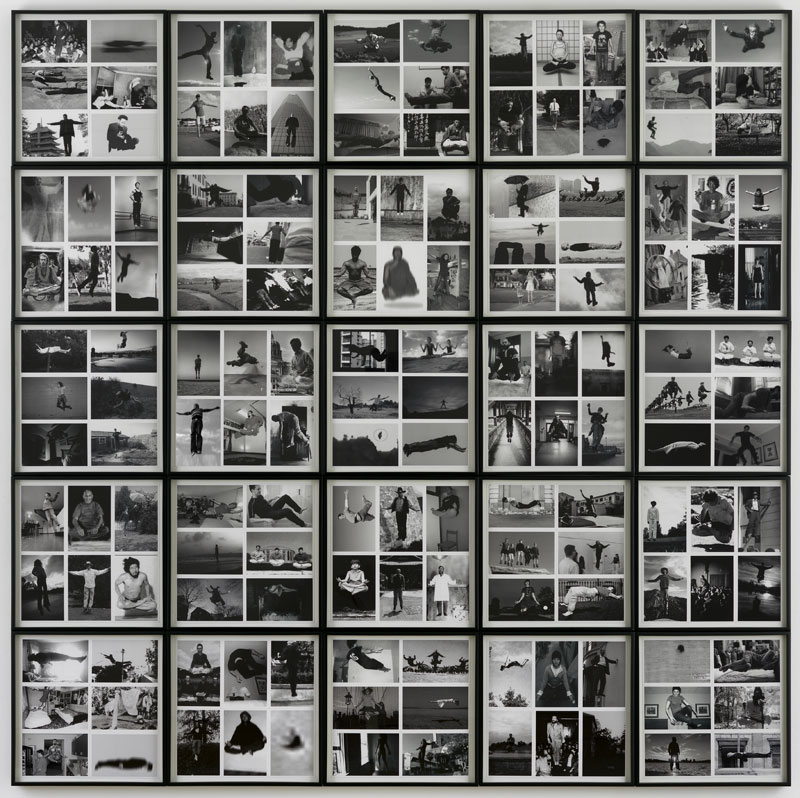

Levitations: Homage to Yves Klein (2008), Susan Hiller © Susan Hiller

Included in the Lisson’s show are a number of little-seen works, many from her early years and many paintings in some guise, like those she made on wallpaper or her Midnight series from the 1980s – photobooth self-portraits she made abstract with paint and automatic writing. Painting is the medium that she is least associated with but she tells me she has never given up on it. ‘The curator at the gallery wanted to show some of these because he thought that they were surprising. They don’t surprise me. They are like my other work – they are only different because they are older.’

In other instances in the exhibition, there are what used to be paintings: Painting Blocks (1970–84), books of chopped-up painted canvases: ‘I turned the painting into sculpture, turned surface into mass’; and glass containers holding the ashes of burnt paintings in her Relics series which she began in 1972. ‘When I started burning my paintings,’ she says, ‘it was at the same time, or possibly earlier than, other artists started making a big deal about the death of painting. So they burned their student work, usually in a kind of statement about the end of painting. That wasn’t my idea at all.’ Hiller continues: ‘I was interested in transformation and the different stages of an object or a work. I was aware in museums, in our society, we’re constantly trying to keep everything the same. We’re always restoring it, keeping it in correct conditions, whereas in other societies this is not the case.’

‘In Africa, they used to create big wooden masks for ceremonies and then after the ceremony they would throw them away. It was no big deal. They could always make another one. The Eskimo do beautiful little carvings from whale ivory and so forth. There was a time when anthropologists visited them in the 1930s and ’40s and the floors of the igloos they used to live in – they had moved out to go hunting – were littered with tiny little gorgeous sculptures. They tried to explain to the anthropologists that the art was in the carving of the thing, not in the thing itself.’

Emergency Case: Homage to Joseph Beuys (2012), Susan Hiller. Courtesy Lisson Gallery; photo: Jack Hems; © Susan Hiller

This idea of transformation is often integral to Hiller’s art and not just its subject matter – like the young children who are seized by telekinetic powers in her installation Wild Talents (1997); the bottles of holy water which promise transformation in her Emergency Case: Homage to Joseph Beuys (2012); or in 10 Months (1977–79), where she documented her growing belly changing like a moon over the course of her pregnancy. She’s not always content to see a piece as final. ‘When you are an artist you can play games with your own work but when it enters a museum you are not allowed to change it.’ It’s something she sometimes finds frustrating. At the Lisson she has reconfigured her installation Belshazzar’s Feast (1983–84), with screens stacked on top of one another like a bonfire rather than one lone television set showing flickering flames in a living room, as the Tate has in its collection. She has also delved back into her ‘Rough Sea’ postcard collection to make a new series On the Edge (2015), which presents 482 postcards from the stormy edges of Britain. She is endlessly fascinated by ‘the whole idea of the miniature sublime. You go on holiday and you want to send some postcards to some people and instead of a beautiful view you get this really wild view. A small crack in the boring everydayness is this wildness of nature that you can unconsciously seek out if you go to a British seaside resort.’

Looking at the palette of works in the show, it’s noticeable that one of the ways Hiller’s practice has changed is in her use of colour, with more recent works increasingly iridescent. ‘One of my very earliest memories is being taken to nursery school. I must have been three. In the doorway to the house was a bunch of prisms hanging up and the whole entrance was covered in rainbows. That was one of the first things I remember. I still feel that way about colour. Everyone loves that kind of effect. One of the sad things is the way we now get all this on-screen. When you look at that fake Tiffany light-shade over there’ – she points to one of many lamps dangling from the ceiling of the bar – ‘It would have been such a pleasure and thrill when the light came through it and you saw the red and the green. Now it’s just kind of ordinary.’

Looking at a work in the show like Enquiries/Inquiries (1973–75), which compares English and American culture, I wonder if her experience as an outsider in Britain informed her practice as much as her background in anthropology? ‘When I first started working,’ she says, ‘things that people might just think of as ordinary, struck me as unusual and fascinating. I do think as a general rule that artists need to go someplace else. Travel is good, but working in other places is really good. Just having to search for the right pencil in a foreign land is an interesting experience.’

Panel from On the Edge, (2015), Susan Hiller. Courtesy Lisson Gallery; © Susan Hiller

The romantic notion of Susan Hiller that I had concocted in my head was of a rummaging, collecting, hoarder-artist. I had read about her salvaging old medicine bottles from the banks of London’s canals. In the middle of one of the Lisson’s galleries are a number of Alfred West’s Split Hairs works (last on show in the treasure trove that was Brian Dillon’s ‘Curiosity’ exhibition). Just like the ‘Rough Sea’ postcards, which highlighted unheralded amateur artistry long before outsider art became fashionable (Hiller titled that 1972–76 project Dedicated to the Unknown Artists), these bring to light West’s intricate virtuosity. She found West’s text pieces all made from human hairs on the street: ‘The split hairs were being thrown away after Alfred died and the vitrine from the museum was as well, as they were renovating it. The museum looks boring now but they had wonderful old Victorian furniture. I believe Damien Hirst has bought most of it.’

However, she professes she’s not a collector: ‘When I was young I collected colour crayons, shells, cards, the usual things. I was never an obsessive. And I’m still not. This is a collection,’ she says motioning around her. Although she does add: ‘I have a few other things that I’ve collected that may turn into works eventually.’ I had imagined her studio brimming with curios. Perhaps it isn’t so surprising to find it so neat, with everything packed away on shelves in boxes with labels. The sight of them sitting there side by side, brings to mind the precise ordering and display of her artworks, like the bottles of holy water, each with their label noting where the water came from.

In addition to collecting, Hiller has also organised exhibitions as an artist-curator, a way of working that many have since copied. Her most well-known exhibition is ‘Dream Machines’, which explored art and altered states of consciousness at the Hayward Gallery in 2000. But in New York in 1981 she also co-curated with Suzanne Lacy a show called ‘We’ll make it up when we meet/aka LA-London Lab’, which gathered female artists from LA and London. I ask her how that came about. ‘I happened to be in New York and the British council or the Tate had organised a big show of British art of the ’70s,’ she tells me. ‘It was all men of course. Martha Wilson who ran a very famous performance and exhibition place called Franklin Furnace came running up at the opening saying, “Where are all the women?” And I said, “Well, this is England and we don’t mention that, it’s not polite.” And she said, “Well I want you to do a show with me.”’ Hiller selected the British participants. ‘There were a number of fascinating artists in it – Rose English, Sally Potter…It was a huge success in New York but of course no one here knew anything about it.’

Auras: Homage to Marcel Duchamp (2008), Susan Hiller © Susan Hiller

In April, Tate Britain is holding a survey, ‘Conceptual Art in Britain: 1964–1979’. Hiller and Mary Kelly are the only two female artists currently listed in the selection. I ask her what it was like working as a female artist at that time. ‘I didn’t have problems with other artists who were men,’ Hiller says. ‘The problems I had were with the administrators and curators, even when they were women. For years and years and years one didn’t even mention feminism. No one wanted to discuss it. I was told by an English gallerist in the ’80s that my commitment to feminism had ruined my career. Postcards, trivia, the things that really interest me are dangerous for a woman, because they reek of domesticity and craft.’

It took a long time for Hiller to come out as an artist, ‘Because I never had any role models. I never heard of any female artists who were really wonderful.’ I mention I read she had a portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe (the subject of a Tate Modern retrospective this year) hanging on her wall when she was younger. ‘That was when I went to University,’ she explains. ‘But I didn’t want to make work like Georgia O’Keeffe so there was this dilemma. There was a cultural sense that women’s art was deficient. As someone who did anthropology I’ll tell you that cultural bias runs very deep. And it’s always backed up by the fact that people say there are no great women artists in other cultures. This is not true. It is something that is being worked on all the time by historians and anthropologists now, but when I was doing anthropology, you went out to a place and no one ever talked to the women; they talked to the men about the women so they got very weird ideas.’

Hiller describes the different attitude towards ceramics in China and Japan, where ceramicists were regarded as artists, to America, where native American ceramics were condescendingly regarded as craft. And in the context of her own work, she explains, ‘When I made sewn canvases that was what women did, sewing. But when male artists made sown canvases at the same time, that was art […]It was hurtful but at the time I thought it was hilariously funny. I only got angry a bit later on when I realised all the damage it was doing, not just to me but to all the other women I knew who were artists.’

But, although Hiller is a feminist, she has never wanted to be ‘a feminist artist’. ‘My feminism,’ she says, ‘is embedded in the work. It’s not on the surface of it. Since I never wanted to make polemical art, which has been another thrust of women’s art, I think my position has seemed a little complex to those who want to label work feminist or not.’

Has the situation changed sufficiently? ‘I think we’ve caught up, maybe not as much as we should have. But it has certainly improved here,’ she thinks. We talk about all the solo shows of female artists that have happened recently: Leonora Carrington, Sonia Delaunay, Hannah Höch. ‘It’s good, but they are being inserted. The canon of works for most people stays male. Eventually that will change though,’ Hiller says. She tells me how much she enjoyed Tate Modern’s Agnes Martin retrospective. ‘Martin had a quiet life. I read someplace that she checked herself into an old people’s home. She could have stayed there all day watching TV but she didn’t. Every day she drove to her studio. She liked living there because they did the cooking and she didn’t have to worry about all of that. That’s great isn’t it? I thought that is for me. That’s a role model.’

Susan Hiller. Photo: Mark Lyon, 2014

Isabel Stevens works at Sight & Sound and writes about art and film for Aperture and the Guardian.