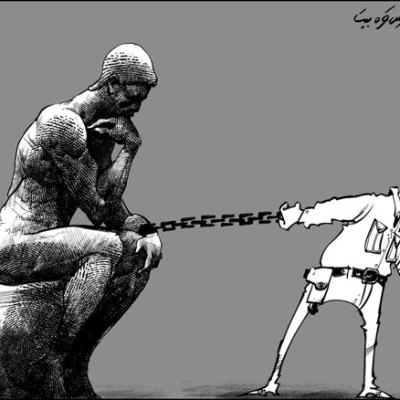

In 2012, against the backdrop of the escalating conflict in Syria, artists, gallerists, and curators began to leave the country in large numbers. When artists had begun to speak out in solidarity with dissidents a year earlier many did so anonymously – in the form of political posters, digital images, or video works that were circulated online among activists. Others who signed their works were forced to flee to neighbouring Lebanon or Turkey, or to Egypt, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates. Many of the images produced in the beginning of the conflict are graphic, drawing attention to the Assad regime’s mounting campaign against activists and oppositional forces.

Before the war, galleries often negotiated the state’s official code of conduct through a delicate balancing act of giving artists the opportunity to express themselves, while warding off the attention of censors. However, some established artists, such as the Aleppo-based photographer and gallerist Issa Touma, defied these rules and were detained or taken in for questioning on more than one occasion. Touma continues to live and work in Aleppo, and also travels to Europe to speak about his cultural activism. Six years ago, he launched Art Camping, a series of workshops that encourages young Syrians to find relief from the conflict by making art. Despite dangerous conditions in the northern Syrian city, in September, Touma plans to hold the 13th edition of the Aleppo International Photo Festival – an event he has organised every two to three years since 1997.

As the war intensified, independent art spaces like All Art Now in Damascus – home to the largest concentration of galleries – closed after finding it difficult to organise the international exhibitions, events, and residencies that were launched during the political reforms of the early and mid 2000s. The founders of All Art Now, Abir and Nisrine Boukhari, tried to continue their mission of supporting local artists in various ways. In 2012, however, when a colleague asked if his displaced family could stay in the gallery’s dilapidated old city building, the sisters conceded and shuttered the venue. Although no longer working in Syria, they remain active abroad.

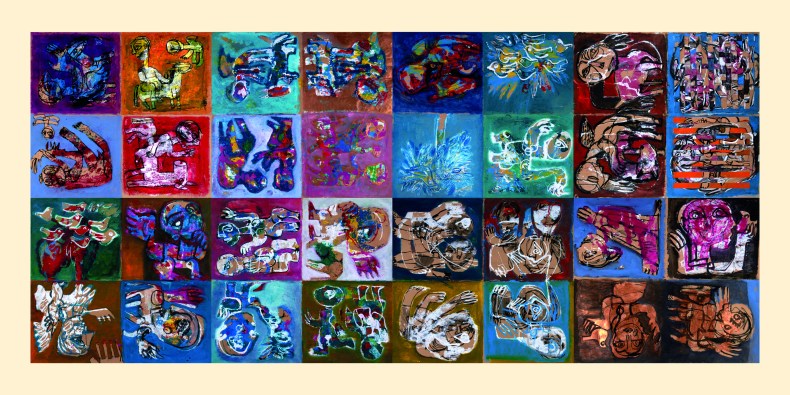

Untitled (2016), Fadi Yazigi. Courtesy the artist

While the population of artists residing in Syria is miniscule compared to the pre-war community that lived and worked in the capital, or in cities such as Aleppo and Homs, those that stayed continue to work even without the backing of a fully functional, albeit relatively small, art scene. The sculptor and painter Fadi Yazigi works from Damascus but also shows it abroad. His most recent exhibition ‘Still Life…Still Alive…Still a Life’ opened at Deborah Colton Gallery in Houston, Texas in February 2017. The show featured new works on paper, canvas paintings, and bronze sculptures that depict his stylised, child-like figures floating or turning in mid air. Yazigi has said that his work has served as a means of survival, a way to navigate the trauma of the war. In an untitled 2016 work on recycled paper, Yazigi depicts a series of figures, either in pairs or alone, in 32 individual square boxes. Although the boxes are arranged in a grid, the overall effect is chaotic, as the figures appear in impossible positions, detached from physical space, unaffected by the laws of gravity.

The Syrian Network for Human Rights reports that various warring factions were responsible for the deaths of nearly two dozen artists between 2012 and 2015, while the number arrested or held captive during the initial phase of the war has been nearly three times that. News of the death of the sculptor Wael Qatsoun at the hands of government forces in 2012 spread quickly on social media when the Syrian Coalition of Artists for Freedom circulated a statement describing his funeral near Homs. Qatsoun was arrested at his studio, and detained for an extended period of time before being tortured to death. There are also the tragic stories of artists whose children were kidnapped for ransom or taken in for questioning by authorities; some have not been returned.

The few arts organisations still operating in the country are mostly in Damascus, which, although surrounded by fighting, has not been as affected as other cities. The National Center for Visual Arts is an essential venue for art students, and exhibits the work of local artists, while art spaces such as Kozah Gallery and Art House reopened in 2017. Artists such as Buthayna Ali, who lived and worked between Canada and Syria before the war, continue to teach at the University of Damascus’s Faculty of Fine Arts, the leading art school in the country. Art students from across Syria have migrated to Damascus after other parts of the country became unsafe or were completely devastated by the war. This influx of students, combind with the departure of several faculty members for abroad, has made for overcrowded classes.

Ali teaches painting and drawing although her own work takes the form of installations. She resettled in Syria shortly after the start of the war to be near her family and also to support her students. Since then Ali has been drawing in sketchbooks without the intent of exhibiting, unable to conceive of installing public works at this time. She does not feel that the war should inform new artworks: ‘I don’t want to do something on this war,’ she explains via email, ‘but I can’t do anything else. I don’t want to document, I want to make art.’ Although she lives in Damascus, it is impossible to escape the violence that engulfs the rest of Syria. Recently Ali told The Philadelphia Inquirer, that she ‘feel[s] every scream, every bomb’. She insists that the only thing to do as an artist at this time is to pause and wait for the war to end. ‘There are some galleries operating, and some small shows, but in my opinion we can’t see any true works of art in this time of war. It has deeply affected us.’ Her sentiments reflect the widespread fatigue that is expressed among artists throughout Syria and those living in exile. Last year Ali was invited to an artist’s residency in Philadelphia, offered by the non-profit arts organisation Al Bustan Seeds of Culture, but was unable to attend under the new US travel ban.

International news coverage of Syrian artists has created a demand for the work of those who are represented abroad. Or, at least, there is a steady demand for certain kinds of images, as can be seen in the case of Tammam Azzam’s Freedom Graffiti print of 2012, which went ‘viral’ on social media. Some regional art critics, however, reproach artists who fail to offer nuanced depictions of the conflict.

Artists in Damascus without commercial representation complain of collectors who seek to capitalise on Syria’s collapsed economy by offering outrageously low prices for works. But without the backing of patrons or gallerists in Syria, as elsewhere, it is impossible to work as an artist full-time. Moreover, as the security situation fluctuates, the safety of even those living in Damascus is not guaranteed, and resources remain scarce.

The Terror Group (2014), Othman Moussa. Courtesy Ayyam Gallery

The painter Othman Moussa has only recently returned to producing oil on canvas works, and says that he is limited to available supplies. ‘I still draw but only paint sporadically, not as before. Sometimes I have to wait several months to get a specific colour of paint,’ he tells me via text message. In 2013 Moussa created a series of still lifes titled The Terror Group in which – as a nod to the violence that pervades everyday life in Syria, ordinary objects, a hamburger or a set of books, are turned into explosive devices. As the conflict began to close in on Damascus, Moussa retreated to his studio, sketching domestic scenes. His most recent still lifes are less politically charged, and allude to 17th-century Dutch masters.

Beirut once offered a break from the war for Moussa and other artists in Damascus, who often travelled across the border to meet displaced peers or take part in exhibitions. Between 2011 and 2015, the majority of exiles went to Lebanon, where galleries were generally responsive.

In the mountains near Beirut, independent curator Raghad Mardini transformed abandoned horse stables into a non-profit organisation for Syrian artists. Offering a stipend, lodging, and supplies, Art Residence Aley (ARA) is an invaluable resource, assisting those in need of studio space and housing, even if only for a few weeks. Mardini, a civil engineer by training, has become a central figure in the Syrian art scene as both a patron and cultural practitioner, and continues this work with Litehouse Gallery in London.

But Lebanese galleries and audiences seem to have grown tired of exhibitions by Syrian artists addressing a war with no end in sight. By 2015, events featuring this type of work were few and far between. And the worsening political situation in Lebanon has forced many to look for opportunities in Europe. Those who travelled to Istanbul at the start of the conflict also found receptive audiences, but began to face a similar decline in goodwill when the political climate changed and bombings and assassinations began to destabilise the country. The Turkish government has also tightened its immigration policies after becoming more directly involved in the Syrian conflict.

After Lebanon, the second largest number of Syrian artists in exile can be found in Germany. In cities such as Berlin, artists have found various organisations, non-governmental and otherwise, determined to address the growing humanitarian crisis across the Arab world. Several artists, such as Tammam Azzam and Ammar al-Beik, remained in Germany after travelling to the country for residencies or specific events. Both have participated in solo and collective exhibitions in galleries and museums throughout the country.

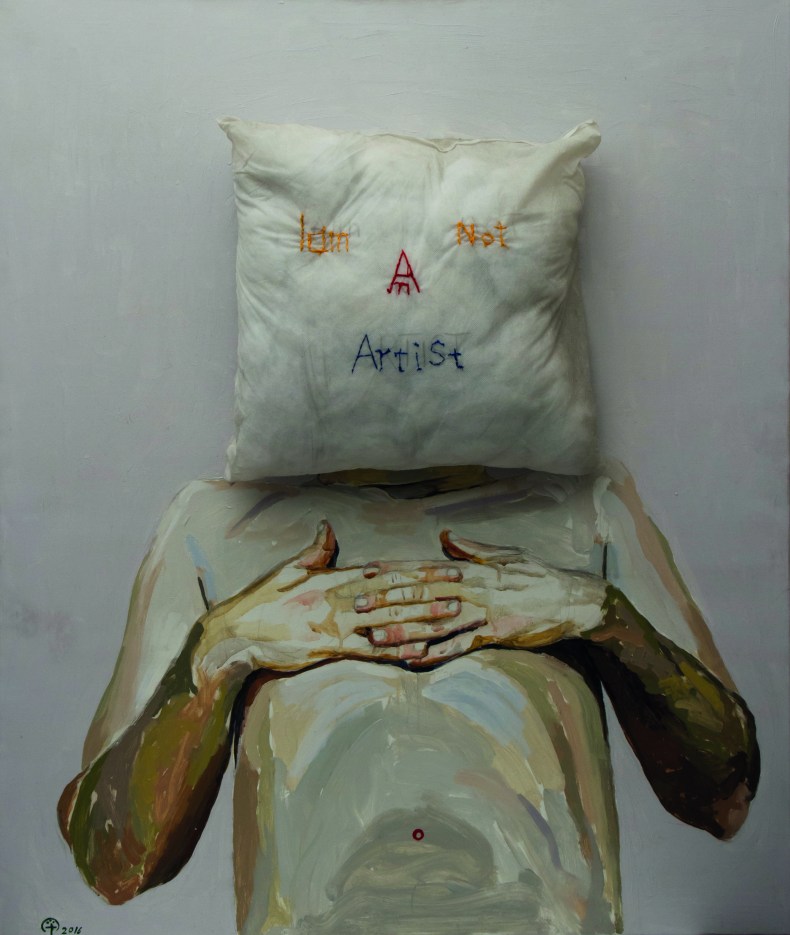

I am Not An Artist (2016), Thaer Maarouf. Courtesy the artist

After living and working in Vienna for several years, the artist Thaer Maarouf says he is fully aware of the cultural politics that can inform European exhibitions. While this politically motivated interest in Syrian art has left some artists reluctant to participate, Maarouf takes a more pragmatic approach, using exhibition opportunities to explore themes that might otherwise be buried or ignored. His latest series of conceptual paintings, I am Not…, addresses the misconceptions and expectations that immigrants often encounter.

The works depict figures whose faces are obscured by a pillow. Embroidered on these pillows are phrases such as ‘I am not a Muslim’ or ‘I am not an artist.’ The pillow symbolises the suffocation that occurs when newcomers are expected to assimilate and conform to narrow categorisations. At the same time, the anonymity of Maarouf’s figures also suggests a profound sense of loneliness. When I spoke to him in October, the artist was careful to note that the series does not directly refer to the Syrian conflict. ‘We can’t effectively talk about the war because we are in the middle of it. Six years on, we are still in shock.’

From the February issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.