From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Some 270 dealers and galleries will bring their best offerings to the European Fine Art Fair (TEFAF), which returns to the Maastricht Exhibition & Conference Centre from 9–14 March. This year sees the launch of Focus, a section for single-artist presentations and themed displays. Here, Susan Moore selects her highlights from the works on display at the fair.

Figure of Bastet (Egypt, Late Dynastic Period, 26th–30th Dynasty; c. 663–332 BC). Rupert Wace, price on application

Figure of Bastet (Egypt, Late Dynastic Period, 26th–30th Dynasty; c. 663–332 BC)

Rupert Wace, price on application

Bastet, the cat-headed daughter of the sun god Ra, was revered as the goddess of fertility, childbirth, abundance, music and joy. This richly detailed votive figure is inscribed on the base in hieroglyphs: ‘May Bastet give life to Amentwyneb son of Hep, begotten by the Lady of the House Timetjet’. With silver-inlaid eyes and pierced ears that once would have held gold earrings, the goddess is represented wearing a short-sleeved sheath dress ornamented with alternating vertical bands of diamond shapes and cross-hatching. In her left hand she carries a menat, a noise-making amuletic necklace bearing a lion’s head, perhaps representing her sister Sekhmet. Her right hand would have held a separately cast sistrum, a rattle-like ritual instrument.

Saint Lucy and Saint Catherine of Alexandria (1384), Bernardo Daddi. Brimo de Laroussilhe, around €1m

Saint Lucy and Saint Catherine of Alexandria (1384), Bernardo Daddi

Brimo de Laroussilhe, around €1m

Daddi’s last documented work, painted before he succumbed to the Black Death in 1384, was a polyptych for the church of San Giorgio a Ruballa in Bagno a Ripoli near Florence. Its sale in the church dispersals of the early 19th century separated the predella panels from the main work, Crucifixion and Saints, now in the Courtauld Gallery. This predella panel, one of five, attests to the artist’s reputation as the most refined and lyrical of the early followers of Giotto. Saint Catherine has her hand on a wheel, the instrument of her martyrdom, her costly brocaded dress a mark of her royal birth; Saint Lucy is identified by the lamp she carries. What makes the panel so affecting is the intimacy and naturalness of the figures.

Pietà (c. 1520–40), Attr: Damián Forment. Galerie Sismann, €200,000–€300,000

Pietà (c. 1520–40), Attr. Damián Forment

Galerie Sismann, €200,000–€300,000

Forment was one of the most important figures of the Spanish Renaissance. Although there are few firm biographical facts, he appears to have been born in Valencia into a family of sculptors before moving to Zaragoza, where he opened a workshop, and then to Huesca, where he established a second studio to produce his most celebrated work, the cathedral’s great alabaster altar. A third workshop operated simultaneously in Tarragona. A real market rarity, this Pietà was discovered by the gallery in 2019. It epitomises the artist’s singular late poetic style, which combines gothic delicacy and Renaissance serenity with a Mannerist expressiveness.

A Bouquet of Flowers in a Wan-li Porcelain Vase (1625), Balthasar van der Ast. Bijl-Van Urk Master Paintings, €1.6m

A Bouquet of Flowers in a Wan-li Porcelain Vase (1625), Balthasar van der Ast

Bijl-Van Urk Master Paintings, €1.6m

Remarkably, this previously unrecorded but signed and dated flower piece came to light only a decade ago. A cabinet-sized panel depicting blooms in a gilt-mounted Chinese vase, it reflects the artist’s debt to his teacher and brother-in-law, Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder, and clearly rejoices in the fauna and flora beloved by both. Here is a painted lady butterfly, a dragonfly, a wasp and a sand lizard whose claws rest on the artist’s signature. Painted in Utrecht shortly before the period of tulipomania, the panel gives star billing to what would become one of the most expensive of tulip varieties – Zomerschoon (‘Summer Beauty’). Van der Ast balances his composition with lily of the valley, forget-me-not and a sprig of scarlet pimpernel.

Versailles vase (Rome, c. 1665). Galerie Steinitz, €2m

Versailles vase (Rome, c. 1665)

Galerie Steinitz, €2m

Carved from rose-tinged alabaster, this large covered vase is gadrooned – its bold, convex ribs twisting in opposite directions around its body and lid. Tapered at one end and rounded at the other, these fluted forms, derived from classical prototypes, are reminiscent of flower petals, while two handles take the shape of satyrs’ heads. The vessel is one of a pair of vases listed in the 1729 and 1775 royal inventories of Louis XIV’s collections. Its identical twin, later mounted in gilt bronze, remains in the Grand Trianon at the Palace of Versailles.

Sir Edward Turner (1643–1721) of Great Hallingbury, Essex (1672), John Michael Wright. Weiss Gallery, price on application

Sir Edward Turner (1643–1721) of Great Hallingbury, Essex (1672), John Michael Wright

Weiss Gallery, price on application

A well-connected lawyer and courtier to Charles II, knighted in 1664 and appointed a Gentleman of the Bedchamber, the sitter is depicted in the particularly sumptuous costume associated with the king’s circle of intimates. Wright records this finery of gold embroidery, ribbons and lace with almost obsessive detail, as befits the symbol of his sitter’s status. It was, as the antiquary Anthony Wood recorded, ‘a strange effeminate age when men strive to imitate women in their apparel’. The cosmopolitan Wright brought a French elegance to British portraiture, and was a connoisseur, collector and dealer as well as a designer of court extravaganza.

Three-dial skeleton clock (c. 1795), Laurent Ridel and Joseph Coteau. La Pendulerie, price on application

Three-dial skeleton clock (c. 1795), Laurent Ridel and Joseph Coteau

La Pendulerie, price on application

The first skeleton clocks appeared in the last decade of the 18th century in response to collectors’ interest in ever more complex and delicate movements. This timepiece by Ridel was decorated by Coteau, the most renowned enameller of his day. The central enamelled ring reveals a portion of its finely finished mechanism and indicates Arabic numeral hours, the Republican date and the days of the week with their corresponding zodiac signs. Two further rings designate months and seasons, and the age and phases of the moon. A mask of Apollo adorns the pendulum.

View of Givet, on the Meuse, South of Dinant (1839), Joseph Mallord William Turner. Colnaghi Elliott, £350,000

View of Givet, on the Meuse, South of Dinant (1839), Joseph Mallord William Turner

Colnaghi Elliott, £350,000

A rare and recently rediscovered French subject, this expressive and well-preserved watercolour shows the artist characteristically more concerned with dramatic atmospheric effects than topography. The solid forms of crag, church, historic fortress and bridge, moored boats and figures blur in the storm above Givet. To the left, the leaden blue-grey sky is pierced by a shard of lightening. Four preparatory sketches for this view are in the Turner Bequest at Tate Britain.

Paysage de neige à Chatou (c. 1904–05), André Derain. Landau Fine Art, price on application. Courtesy Landau Fine Art, Montreal & Meggen

Paysage de neige à Chatou (c. 1904–05), André Derain

Landau Fine Art, price on application

In 1904 Derain returned from military service to the studio he shared with Maurice de Vlaminck in the Paris suburb of Chatou. The following year the pair made their fateful trip to the southern fishing town of Collioure to join Matisse, where they developed a new visual language of expressive, non-naturalistic colour and rhythmic, energetic lines. Distinctions between foreground and background, light and shadow, were exploded and broad dabs of often pure pigment were applied to unprimed grounds. Here a tranquil snow scene is transformed by bold, staccato passages of vermilion and crimson, lime and aquamarine.

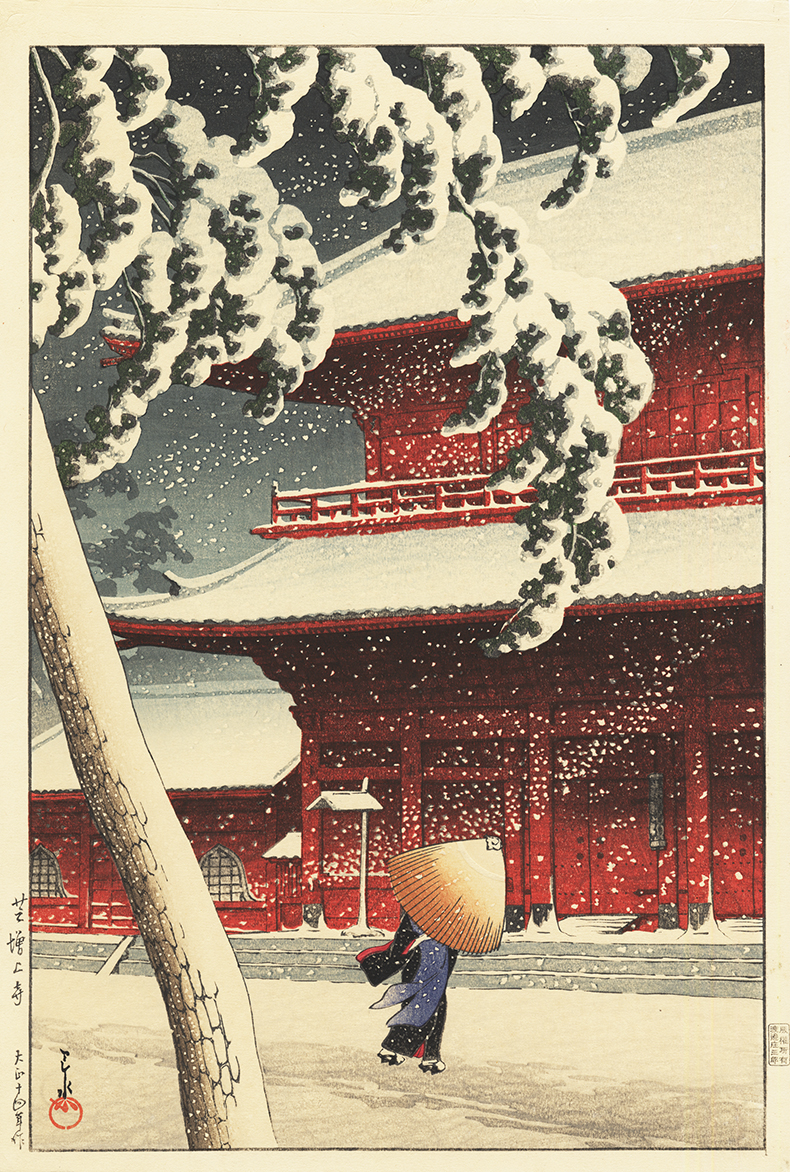

Zojoji Temple, Shiba (1925), Hasui Kawase. Tanakaya, €48,000

Zojoji Temple, Shiba (1925), Hasui Kawase

Tanakaya, €48,000

Hasui, a Living National Treasure, was a prominent and prolific designer of the shin-hanga (‘new prints’) movement influenced by Western painting. Renowned for his technically demanding and naturalistic atmospheric effects, he made the first of his highly original prints of falling snow in 1920. This one, which belongs to the series Twenty Views of Tokyo, is perhaps the most famous. This first edition combines the highest-quality paper, very dense inks and extreme precision in both wood-engraving and printing.

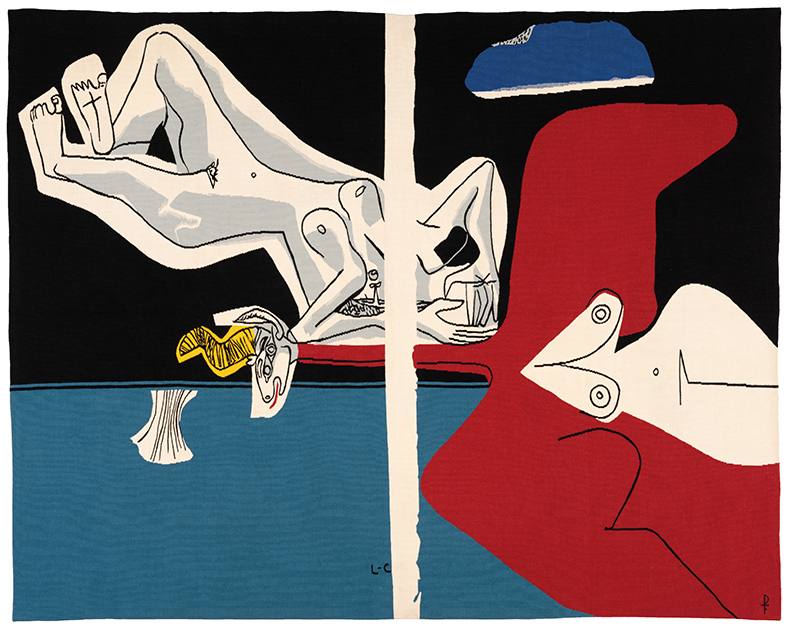

The unicorn passes over the sea (1962), Le Corbusier. De Wit Fine Tapestries, price on application

The unicorn passes over the sea (1962), Le Corbusier

De Wit Fine Tapestries, price on application

‘The destiny of the tapestry of today emerges: it becomes the mural of the modern age,’ wrote the modernist architect, theoretician, painter and sculptor Le Corbusier. His collaboration with Pierre Baudouin and Pinton Frères at Aubusson began in the late 1940s and resulted in some 30 designs made from specifically conceived paintings and drawings. Le Corbusier described these tapestries as ‘Muralnomad’ – nomadic murals – ideal for a modern age in which people often move house. Designed to cover entire walls, such works were intended to be seen as part of the architecture. This example is signed by the artist and the workshop and is number three from an edition of four.

Quantum Pocket IV (2010), Elizabeth Fritsch CBE. Adrian Sassoon, $90,000–$100,000. Photo: © Sylvain Deleu

Quantum Pocket IV (2010), Elizabeth Fritsch CBE

Adrian Sassoon, $90,000–$100,000

There are few ceramic artists who combine technical proficiency with intellectual rigour and range. Fritsch is one of them. This handmade vessel investigates space in two and three dimensions, exploring the paradoxical effects of curves and flatness. An ingenious piece of Op Art, it comprises a flattened oval form given the illusion of roundness by its painted lattice of cuboid forms of diminishing scale: rectangles within rectangles, each different in size and angle. This series was inspired by Jorge Luis Borges’s short story ‘Death and the Compass’ (1942) and is typical of Fritsch’s investigations into metaphysics, mathematics, music and literature.

From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.