From the February 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In their quest to achieve eternal life, the kings of Korea’s Joseon dynasty commissioned mystical screen paintings packed with symbols of longevity. Yeonsoo Chee of the Art Institute of Chicago decodes a 19th-century masterpiece.

In Journey to the West, a Chinese novel published in c. 1592 but mostly comprising centuries-old folk tales, a simian trickster named Sun Wukong – aka the Monkey King – hungers for immortality. He is appointed guardian of the heavenly peach garden, in which the trees bloom every 3,000, 6,000 and 9,000 years; the fruit they bear grants eternal life. Sun Wukong’s appetites quickly get the better of him and before long he has gobbled up every peach in the orchard.

Where Sun was blessed with superhuman strength, invisibility powers and the ability to clone himself at will, the kings of the Joseon dynasty in Korea (1392–1910) were less well equipped to live forever. But that doesn’t mean they didn’t try. One of the Chinese belief systems that had flourished in Korea during the preceding Goryeo dynasty (918–1392), together with Confucianism and Buddhism, was Daoism. While Buddhism revolved around suffering and renunciation and Confucianism was concerned primarily with social structures and ethics, Daoism encouraged its practitioners to seek an underlying natural order, live in harmony with it and cultivate enough cosmic force, or qi, to unlock eternal life in a heavenly realm.

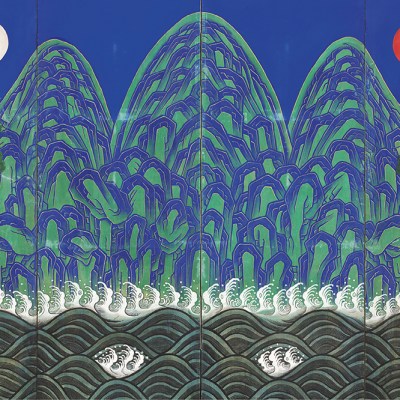

One way in which Joseon kings strove to achieve this was by having their officials commission paintings that represented long life. Ten Symbols of Longevity, a folding screen painted by anonymous Joseon court artists in the 19th century and now held by the National Museum of Korea, is one magnificent example. Its 10 panels depict the kind of lush paradise in which Daoist deities were believed to live forever. In many East Asian cultures, 10 is considered the number of perfection; the 10 symbols of longevity appear in China and Japan as well as in Korea. But this particular compositional approach, with its insistence on including all 10 symbols, is unique to Korea. In fact, despite the title, 12 traditional symbols of longevity are visible in this work: the sun, mountains, rocks, clouds, water, cranes, deer, tortoises, lingzhi mushrooms, bamboo, pines – and, of course, peach trees.

Each motif symbolises immortality in its own way. The sun (and the moon, which appears in other paintings depicting this theme) represents the universe, ever-present and timeless. The clouds represent the atmosphere, which, along with water, is another permanent feature of life on earth. Cranes and clouds would often be painted together as a joint symbol of longevity; with their slender necks and graceful bodies, cranes were considered semi-divine creatures. In several Korean myths and folk tales the crane is an embodiment of a heavenly maiden and ends up transfiguring itself into a lady.

Bamboo and pine are evergreen; mountains and rocks exist more-or-less unchangingly – all apt for a painting about longevity. Rocks also symbolised enduring friendship and loyalty among scholars and gentlemen. As for the terrestrial creatures, the significance of turtles, with their long lifespans, scarcely needs explaining. More intriguing are the deer, which are a prominent part of this painting. The direction in which they are trotting suggests that, like other Korean panel paintings, this work was intended to be read from right to left. Deer have long been closely linked with the shamanistic tradition in Korea, an association that precedes the arrival of Daoism, Buddhism or Confucianism; they were considered near-mythical creatures on account of their majestic antlers. They were also worshipped in Siberian shamanistic traditions, which treated them as a symbol of the kingly or the divine. (The border between modern-day Russia and Joseon was not established until the 19th century, after hundreds of years of cultural traditions flowing back and forth.) As well as depending on deer in practical ways – wearing their fur and eating their meat – Siberians and Koreans revered these creatures and, from the third until the sixth century, deer antlers were used to make crowns for kings and shamans.

The pointed, reddish mushrooms towards the bottom of the painting are lingzhi, known in Korean as yeongji and believed to be a key ingredient in the elixir of immortality. Certain mushrooms may also have been consumed to induce a trance-like state in shamans about to administer religious rites. Lingzhi are still widely produced and consumed in Korea: they sometimes make an appearance in cuisine, but thanks to their earthy, slightly bitter taste they are more commonly used in herbal remedies and drinks.

There is little sense of reality in Ten Symbols of Longevity. Though full of earthly imagery it seems otherworldly; real mountains are not made of discrete blue and green blocks. Rather than blending colours, the painters used saturated hues and gave many of the objects prominent black outlines, resulting in a flattened pictorial space and a distinctly graphic quality – a style that had been prevalent in dynastic painting for centuries. To achieve such intense colours, the painters applied multiple layers of mineral pigments bound with animal glue. Paint in 19th-century Korea was derived from mineral pigments: azurite or cobalt would make blue, malachite green, cinnabar red. These were rare minerals, mined or imported at great expense.

Some records of individual court painters do exist, but these artists did not sign their works; the art was not associated with their individual identity or artistry. Court painters worked as a group. That said, among the court painters there were certain stratifications. First-rank painters were responsible for royal portraits, which were of the utmost importance: the king’s portrait was thought to embody the king himself and would stand in for the king when he was not present. Ten Symbols of Longevity would probably have been painted by a first-tier artist, given the expense involved and the skill required. Second- and third-tier painters were artisans who, despite being employed by the court, were not paid especially well. They had myriad responsibilities besides painting; one of their most frequent tasks was to draw the lines for books that would contain records of the king’s daily life.

The king was considered a semi-divine figure connecting the heavenly and earthly realms. His residence, wherever it happened to be, was thought to have a special aura and the environment in which he moved was highly ritualistic. The paintings that decorated the court had specific meanings: their function was not only aesthetic but also political and cultural, conveying an embedded code. Court painters had to pass exams that would test their aptitude for getting this code across in portraits and landscapes. This was all overseen by the Dohwaseo – the royal bureau of painting. That doesn’t mean the artists lacked inventiveness: they still had to find ways to express meaning through colour, composition and the harmonious interplay of symbols.

The Dohwaseo was part of the ministry of rites, the body that would have commissioned this painting. There was a process that had to be followed. The most skilled painter would draw the outlines for inspection by ministry officials, who were well versed in the visual vocabulary of Confucianism and Daoism and would ensure that the artists were following the correct sort of template. If they approved the design, it would be rendered as an underpainting, with indications of what colours would be used where. Several court painters would then get to work on the painting. The underlying structure is a lattice covered with several layers of backing paper; the paint would be applied to that and then the borders would be framed with silk.

The panels themselves also had a highly regulated format: there were prescriptions for which alloys to use for the nails and how many nails should be used. Though folding screens were present in China, Korea and Japan, the hinges varied from place to place; in Korea the hinges involved a slit in the side of each panel. The wood itself was pine, bamboo or paulownia, which could withstand potential damage by insects. Folding screens ranged from two panels to ten – the latter being the most extravagant format, reserved for birthdays and weddings as well as celebrations of royal figures’ recovery from serious illness. Successful recuperation was often marked with a great banquet, where folding screens celebrating longevity and prosperity would be displayed in daecheong maru (open wood-floored halls), stand behind the main seat in a room or be used as backdrops in courtyards.

Given the highly codified nature of panel paintings about longevity, there are similar paintings and embroideries in other museums’ collections, dating from the late 18th century and after – though such works are believed to have been made as early as the 14th century. But by any standard Ten Symbols of Longevity is an exquisite sampling of the conventions of Joseon court painting. The mountains are rendered as fantastical landscapes, typical of the Daoist paradise where immortals reside; the clouds fill the expanse of the sky, adding both visual rhythm and decorative charm. The pine trees are prominent in the foreground and the whole thing seems like it’s been composed in discrete layers, rather than having the depth that we see in European landscape painting. It’s not that Korean court painters didn’t know how to create depth – it just wasn’t their primary concern when concocting a mythical paradise.

The colour scheme is also fit for kings. Red was a sacred colour and the colour of the royal family – no surprise, then, that the sun in Ten Symbols of Longevity is a deep shade of cherry. It’s also visible in the pine trunks; the Korean red pine is widely considered the national tree of Korea. Like the peach tree, the pine also plays a part in folk legends. In the 15th century, King Sejo of Joseon was on his way to some hot springs when he almost got his palanquin caught in the branches of a Korean pine. As he ordered his bearers to look out, the pine is said to have deferentially raised its branches to let him pass. Impressed by its loyalty, Sejo gave it the rank of Jeongipum – essentially making it a cabinet minister. The tree is still there today, in Boeun-gun in central South Korea, and has grown some 15 metres high – a symbol of longevity if ever there was one.

As told to Arjun Saijp.

Yeonsoo Chee is associate curator of Korean art at the Art Institute of Chicago.

‘Korean National Treasures: 2,000 Years of Art’ is at the Art Institute of Chicago from 7 March–5 July.

From the February 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.