On a quiet side-street off Queen’s Road in Peckham, South London is a three-storey block of private flats. Only the modernist lines of the building and a blue plaque behind its electronic gates give a clue to its history: this was once the Pioneer Health Centre, home to the Peckham Experiment. The centre and the experiment it housed were the brainchild of two doctors, Innes Hope Pearse and George Scott Williamson, who chose the site in the 1930s as a place to study ethology, human health and flourishing, which they opposed to the usual medical focus on pathology or disease.

Ilona Sagar’s exhibition ‘Correspondence O’, currently on show on the other side of Peckham at the South London Gallery, delves into the history of this experiment and its home, designed by the engineer-architect Owen Williams and opened in 1935. The exhibition’s centrepiece is a two-channel film (also titled Correspondence O) that draws on extensive archival research and features the centre’s spectacular and slightly dilapidated glass-roofed swimming pool, which still fills the interior of the building with light that bounces off the water’s surface and through the many internal windows.

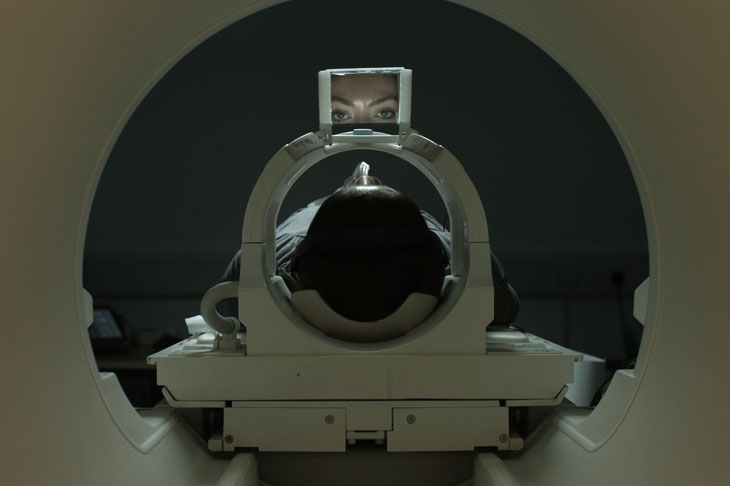

Correspondence O (still; 2017), Ilona Sagar

Translucency and its relation to knowledge were at the heart of the experiment. Williamson told the centre’s members, who joined to use the swimming pool and other ‘instruments of health’ including a gym, billiards tables, a self-service café and a sprung dance floor, that they were ‘guinea pigs’, participating as both data and instruments in a grand experiment to understand human health. The centre’s glass windows, moveable partitions and obligatory medical ‘overhauls’ were all part of this project. As Pearse later wrote, the human biologist’s ‘new “lens” is the transparency of all boundaries within the field of his experiment.’

Sagar picks up on this idea in her film: two of its central motifs are the scanning of the interior of the building using LiDAR technology, and the scanning of a human subject (the film’s protagonist) using an MRI scanner. The work is interested both in the eerie computer-aided images that these procedures generate and in the practicalities of their production, as it lingers on a building surveyor in swimming shorts positioning the LiDAR sensor in the pyramidal swimming pool chamber, or the medical subject as she is carefully immobilised and prepared, a tube placed into her mouth, her body slid into the bore of the scanner.

Correspondence O (still; 2017), Ilona Sagar

The visual juxtaposition of these processes suggests we should treat them as analogous, but the force of the analogy is not immediately drawn out. The film doesn’t attempt to directly answer how a body might be like a building, or a building like a body – instead, a kind of synthesis of these motifs occurs as the medical subject-protagonist is shown swimming through the pool.

This is one of several questions that Sagar evokes but refuses to resolve. Another concerns the politics of health, which becomes especially salient when the film’s voiceover rehearses a sequence of queries reminiscent, in their sinister banality, of 21st-century work capability assessments. Elsewhere, the narrator asks: ‘How to understand the position of the claimant… client?’ Creating or imagining positions for ourselves as citizens outside the claimant/client binary is a politically urgent task, and the Peckham archive, like the ruins of many cancelled futures, provides abundant resources for this kind of speculative thinking.

Rightly, though, Sagar refuses to treat the archive as a wholly utopian space. Over a present-day image of someone doing sit-ups, her narrator intones: ‘good rest – hard worker – morally adequate’. As at several other points in the work, it’s hard to tell if these disconnected verbal fragments originate in the historical material or today’s world of individualised medicine. This slippage is interesting as it buries the hook of responsibility deep in Peckham’s past, in an archive which holds together fiercely contradictory materials, ranging in tone from the implicitly anarchist to the deeply conservative.

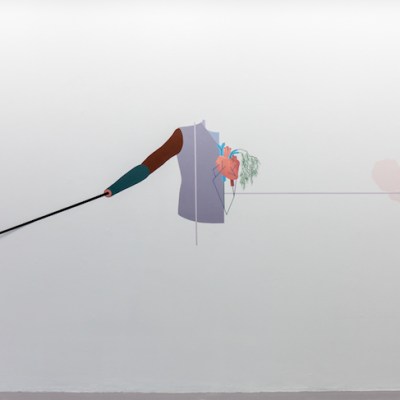

Correspondence O (still; 2017), Ilona Sagar

Like the archive, which is represented in an adjoining room through a small selection of printed matter, photos and oral histories, the film holds its dispersive materials loosely enough that the relationships between the parts can shift and reconfigure in the mind of the viewer. The voiceover is disjointed, almost to the point of functioning as a verbal mulch or compost, so most of this work happens through a specifically visual stitching. The artist’s contemporary moving images parallel, echo and elaborate on the details of the archival film clips they are intercut with: swimmers mingling with bodies of water, gymnasts’ bare feet on cork tiles, individuals undergoing scientific assessment. These visual threads, rising and then falling back into the body of the film, allow Sagar to create a dense and allusive work that draws on the past without becoming trapped in a form of re-enactment.

‘Ilona Sagar: Correspondence O’ is at South London Gallery, until 25 February.