For the third edition of TEFAF’s Curated section, Penelope Curtis, director of Lisbon’s Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, explores the theme of the recumbent or reclining figure in art. At the opening of the Maastricht fair, she discussed her inspiration for ‘La Grande Horizontale’, and the challenges and surprises of putting the display together

How did you come to curate this section of the fair?

I was invited by Hidde van Seggelen, who’s on the board of TEFAF and is trying to bring new things to the fair – new galleries and maybe different kinds of art, too. He introduced the Curated section two years ago: Sydney Picasso did the first one, and Mark Kremer the second. Just before TEFAF last year he invited me to come out and have a look, and then I discovered during a speech at dinner that I was going to be invited to do the 2017 version! Somehow I already knew that the theme I wanted to try and pull off was the reclining figure, and I wanted to do it with a mixture of old and new things.

What’s the process of putting together a display such as this?

In a way we’ve invented the process as we’ve gone along. I thought that we could ask anyone to put forward a reclining figure from the historic section, but that never happened. So in the end the historic items came together at the end – I just went round galleries, and said ‘Do you have any reclining figures? Can I have a look?’ and then chose the ones that made sense. That all happened quite quickly, and quite easily. More complicated was choosing the contemporary aspect. I already had a line-up of artists in mind, but the galleries that represented them didn’t necessarily want to come to Maastricht. TEFAF is expensive and lasts a long time: if you’re a small gallery with not a very big turnover, it’s quite a big deal to have to have someone looking after the material for two weeks. About half the galleries said yes and half said no, and then I’d have to think again. Sometimes I knew the galleries – Aurel Scheibler and Andriesse Eyck, for example – more than the artists, whereas in other cases, as with Ettore Spalletti or with David Tremlett, I knew the artists, and they brought their galleries along.

You open your catalogue essay by discussing Henry Moore. Was his work the starting point for this display?

It began with the reclining figure – a Henry Moore type figure. So I had a standard ‘Moore’ in my mind – at least you might put it that way – and Thomas Schütte was an immediate link from that. Then I think I managed to open it up into something that was more abstract, so the horizontal goes from the figure to the landscape.

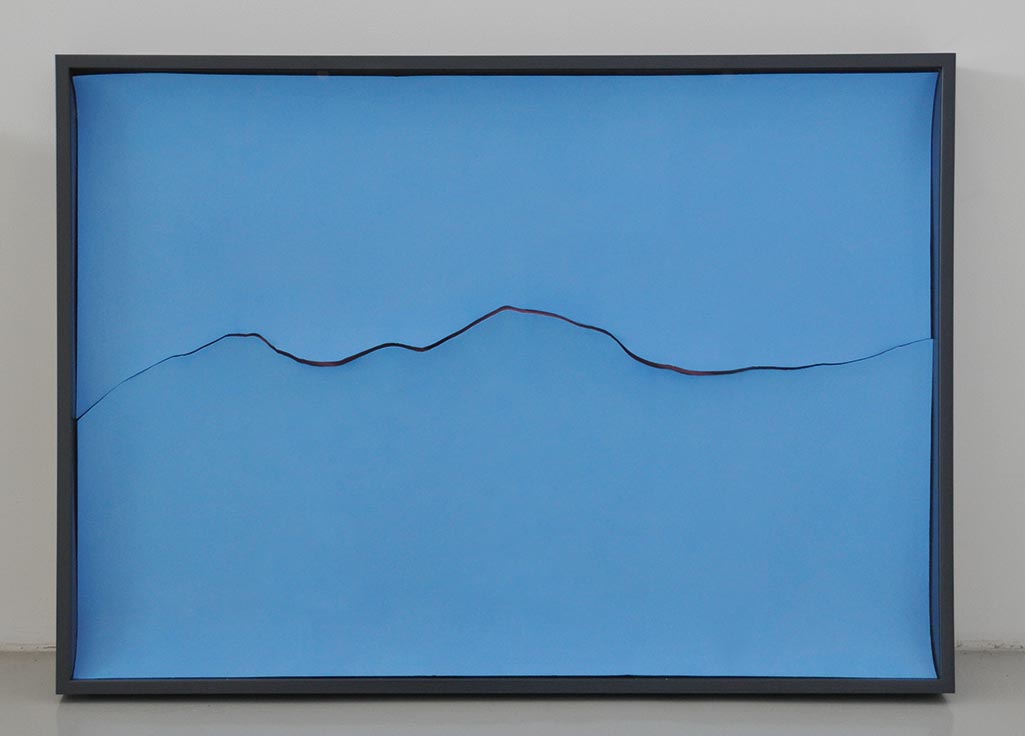

Ettore Spalletti’s Sleeping Beauty is one example of this. How do his abstractions spring from the figure and the landscape?

Sleeping Beauty is a story and an image that’s always stayed in my mind. Some time ago, when I was working with Spalletti, I stayed in his house for quite a long time, and he drove me around the area where he grew up. There was this line of hills called the Sleeping Beauty, which he was obsessed by, seeing it in every kind of weather and every kind of light, and trying to capture that. This piece is an exact mix between the figurative and the abstract. Fundamentally in Spalletti’s work the blue is always the sky or the landscape, and the pink is the body – so his much more abstract pictures are still about the body and the landscape. He just became more and more abstract with it as he got older.

Reclining figures – particularly depicting women – sometimes have a sense of vulnerability to them compared to standing ones. Is this something you feel in the display?

You might be right. I hadn’t really thought about that. But sometimes you see reclining figures that are greatly at ease, so they don’t look vulnerable – they look absolutely comfortable. The reclining Buddha, for example, looks inviolable, really. The ones that get most attacked are the works by Thomas Schütte: there’s a whole discussion about what Thomas is doing with those reclining figures, because you can read into them a strong male/female dynamic. What does this mean if a man makes reclining figures like that?

How did you come across Charlotte Dumas’s work, which features a reclining horse rather than a figure?

That came from the gallery. I hadn’t thought about reclining animals, although there’s a whole tradition in the 18th and 19th centuries of statuary of reclining horses and dogs. It was Andriesse Eyck who said Charlotte Dumas’ films might fit in. I didn’t immediately think ‘yes, of course’, but then I saw them and read about them, and I think it works. You were talking about vulnerability: these horses take the dead bodies of American military personnel to the cemetery, and they work very hard. Apparently by the end of the day they’re absolutely exhausted. This is them recovering, recuperating.

How does curating a display at an art fair compare to museum curating? Does it offer any new opportunities?

I suppose in a museum you’re more in control. Here you have to let go more, and sometimes the results are unexpectedly good. I don’t know whether that is something that a museum curator would want to embrace… But this display is more heterogeneous than you would have in a museum, and that was slightly risky. But in the end, we kept control of it – it still makes sense.

Even when we were talking about possibilities that didn’t immediately make sense, we could find certain works that did. In the beginning I wasn’t convinced that Suchan Kinoshita’s work was enough about the horizontal, but the light in David Tremlett’s Horizon picks up the light of the water [in Haiku for Liège] and the way that the liquid finds its level, so actually in the end it was quite successful.

I like the idea of a display of recumbent figures at a busy art fair like this. Last year at Frieze London, AYR Art Collective invited people to lie down on beds as part of their exhibit… Were you tempted to do something similar?

I didn’t think of that at all, although I have done that occasionally myself in exhibitions… In fact, the gallerists were desperate to make sure that they had chairs, which didn’t arrive until the last minute. They were rather anxious. Now the chairs are here, but no beds!