Lucas Cranach (1472–1553) is today acknowledged as one of the great painters of the Northern Renaissance, the creator of a large number of remarkable paintings in a distinctive, highly recognisable style. He was also responsible for the iconic series of images of the Protestant reformer Martin Luther (1483–1546), his friend and contemporary who had also settled in the small north German city of Wittenberg. His images of Luther and friends provide the definitive pictorial chronicle of the reformer’s life, from the time he first burst on to the public stage, and into old age. All of the many books that celebrate Luther in this run-up to the 500th anniversary in 2017 of the publishing of his 95 Theses will draw on Cranach for their image of the reformer. So too will the exhibitions organised under the aegis of the Luther Exhibitions USA 2016 project: ‘Word and Image: Martin Luther’s Reformation’ at the Morgan Library and Museum, New York (7 October–22 January 2017); ‘Law and Grace: Martin Luther, Lucas Cranach, and the Promise of Salvation’ at Pitts Theology Library, Emory University, Atlanta (11 October–16 January 2017); and ‘Martin Luther: Art and the Reformation’ at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (30 October–15 January 2017).

These were some of the most copied pictures of the 16th century; not least because Cranach deliberately developed a workshop practice which facilitated the production of multiple versions. Even so, these paintings would only have had a relatively restricted contemporary reach. We can, however, go further and say that despite the enduring magnificence of these images, in terms of his service to the Reformation Cranach’s greatest achievement lay elsewhere, in other parts of his enormous output.

Here we need to be aware of two great, but comparatively understudied innovations emerging from Cranach’s workshop. The first was the transformation of the woodcut from a relatively undervalued medium of artistic expression, to a powerful tool of evangelism. The second was the development of a model of cultural industrialisation that enabled images to be produced on a sufficiently large scale to serve a movement of ideas growing at a quite remarkable rate between 1517 and 1525. It was during these years that Cranach created the images that defined the new movement, and organised their production in industrial quantities. It was an extraordinary act of cultural innovation: all the more so given it was accomplished in a place, Wittenberg, that up to this point had hardly registered on the cultural atlas of the Holy Roman Empire.

Lucas Cranach was born in 1472 in Kronach, Franconia. He spent his formative years as a master painter in and around Vienna. In 1504 he accepted an invitation to join a team of distinguished painters working on the decoration of Frederick the Wise’s newly remodelled castle and its church in Wittenberg. It was here that he met Albrecht Dürer, another artist commissioned by the ambitious Elector to work on his prestige project; the two painters became and remained friends. However when Dürer and the other contracted painters finished their assignments, Cranach stayed on to work as Frederick’s court painter. This proved to be the ideal role for a man of Cranach’s talents. It required above all versatility; a court painter was expected to turn his hand to anything the employer required, whether this was painting walls, designing court entertainments, portraits, or, in Frederick’s case, hunting scenes. Cranach rose to the challenge. He had the reputation of someone who worked very quickly – ideal for answering the whims and fancies of a prince. He also proved adept at managing a team. He soon became very close to his princely employer, a trusted counsellor as well as an admired artisan. In 1508, the year Cranach was sent to the Low Countries to negotiate a family marriage on the Elector’s behalf, Frederick granted the painter his own coat of arms. Cranach, indeed, was on much more intimate terms with Frederick the Wise than Luther would ever be.

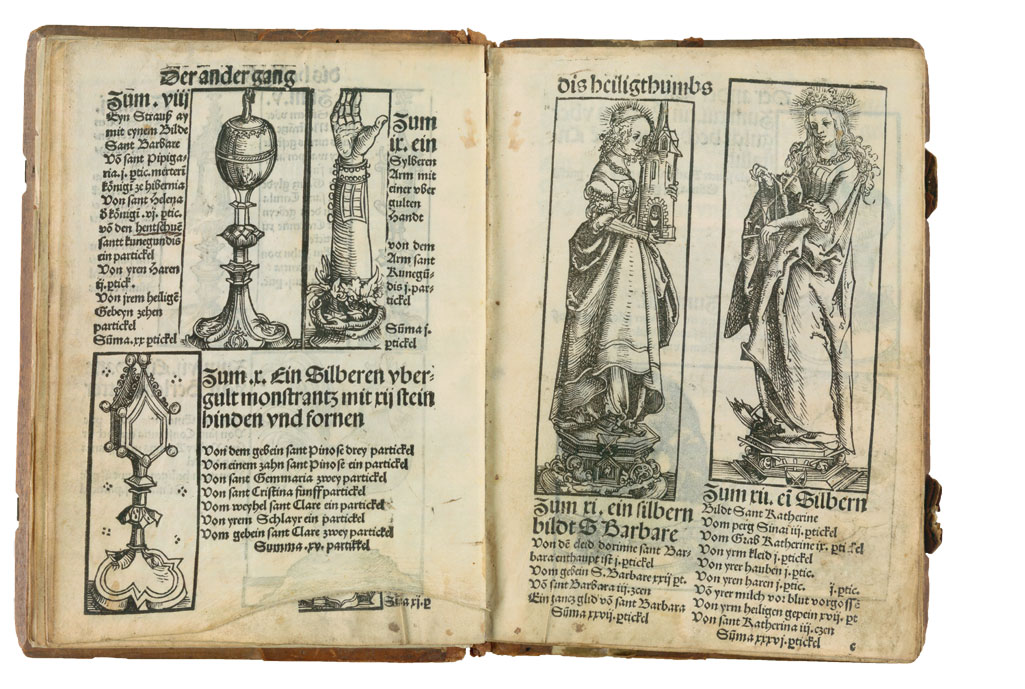

In the years before the Reformation we can identify two seminal moments in the development of Cranach’s business and career path. The first came early, with the commission in 1508 to create a catalogue of Frederick’s growing collection of relics: it is often noted, usually for its delicious irony, that Elector Frederick had one of Europe’s largest relic collections. The task of compiling such a catalogue, which would be adorned with over 100 woodcuts of the major pieces, was a considerable undertaking, particularly in Wittenberg whose printers had, up until now, produced only brief literary pamphlets and dissertation texts for the professors and students of the university. No doubt Frederick underwrote the cost, but Cranach was required to supply the illustrations. The printing was contracted to Simprecht Reinhart, an employee of Cranach’s who may also have incised the woodblocks. Cranach had experimented with woodcuts, and also engravings before, but this was his first sustained engagement with a medium that would come to define his contribution to the Reformation. The Reliquary Book opened his eyes to the potential of woodblocks as a means of mass communication, and as a commercial opportunity: witness his subsequent series of prints on the passion, in competition to those of Albrecht Dürer.

The Wittenberg Reliquary Book (1509), text by Georg Spalatin and illustrations by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt

By the time he had completed the Reliquary Book Cranach was doing extremely well. The role of court painter was well paid, and, crucially, not exclusive; Cranach was at liberty to accept other commissions. As the most distinguished painter in north-east Germany, work was not hard to find. It was in these years that Cranach began to assemble the remarkable portfolio of Wittenberg properties that were the most tangible symbol of his dominance of the local economy. Between 1511 and 1517 he purchased and renovated the two most substantial of these properties, at Schlossstrasse 1 and Am Markt 4, both in the centre of town. Here he would create an elegant town house and, at Schlossstrasse 1, a gigantic building that would be both a residence and a factory/workshop for his growing workforce. By 1517, when he took full possession of the rebuilt Schlossstrasse property, Cranach had the means to create not only great art, but great art in bulk.

By now Cranach had most certainly met Martin Luther, the second seminal event for the artist during these years. Luther settled in Wittenberg in 1511 and by 1514 he was combining his responsibilities in the university with preaching in the town’s only parish church. As a member of the congregation, Cranach would first have come into contact with Luther here: the two became firm friends. In 1517 Luther would stand as godfather to Cranach’s last child, and Cranach would return the favour when Luther began a family. In fact Cranach and his wife were two of the very small number of witnesses at Luther’s controversial marriage in 1525. From the beginning Cranach was a firm and important supporter of the Reformation. This was a relationship of mutual respect, mutual affection and mutual benefit. Cranach provided the Reformation with some of its most memorable images; in return, Luther took a strong line against the radical rejection of pictorial art promoted by some of his Wittenberg colleagues.

Cranach was a crucial ally, and not merely because of his artistic talents. By this point he was one of Wittenberg’s leading citizens, firmly established among the city’s ruling elite. He would play a crucial role in this regard when Luther was absent from Wittenberg in 1521, and over-enthusiastic supporters, led by Andreas Karlstadt, pressed for radical changes to the order of worship that Luther would not have approved. Cranach, civic leader and artistic entrepreneur, was one of the rocks on which the Wittenberg Reformation was built. He also had the managerial skills and resources to conceive a solution to the problem that might otherwise have stopped the Reformation in its tracks: how to build a mass movement from a small place with extremely limited infrastructure. Until 1517 Wittenberg had only one commercial printing shop, run by the patient Johann Rhau-Grunenberg who had undertaken the routine printing of a small provincial university, but who was utterly unprepared for the gear change required by the firestorm set off by Luther’s 95 Theses criticising indulgences.

By 1518, when Luther’s works began to be reprinted in large numbers in other parts of Germany, it was already clear that Rhau-Grunenberg’s work was far inferior to that of printers undertaking their own editions of Luther elsewhere. He was also dreadfully slow. Aware that the situation could not be allowed to continue, Luther intervened. An experienced printer from Leipzig, Melchior Lotter, was persuaded to open a branch office in Wittenberg, to be managed by his son, Melchior Junior. And Cranach was closely involved in this whole scheme; he gave the new workshop space in his great factory at the Schlossstrasse. The look of Wittenberg’s Luther imprints improved immeasurably, but this was still essentially the look of Leipzig: there was nothing particular to Wittenberg in the appearance of Lotter’s books. This required a more decisive intervention on Cranach’s part.

Cranach was in these years intimately involved in the printing industry. As ever, he had prepared the ground carefully. To secure access to the necessary raw materials he purchased a paper mill; to facilitate marketing he entered into a partnership with Christian Döring, who ran a trucking business. Having achieved this precocious feat, Cranach and Döring even published a few books on their own initiative, but this was soon allowed to lapse. Cranach did not need to publish his own books to dominate the market: because of his monopoly of woodcut illustrations, Cranach soon made himself indispensable to anyone active in the growing Wittenberg publishing industry, both to Rhau-Grunenberg and Lotter, and the new generation of printers who arrived in the mid 1520s. And by doing so he transformed the look of the Reformation book and the fortunes of the Wittenberg printing industry.

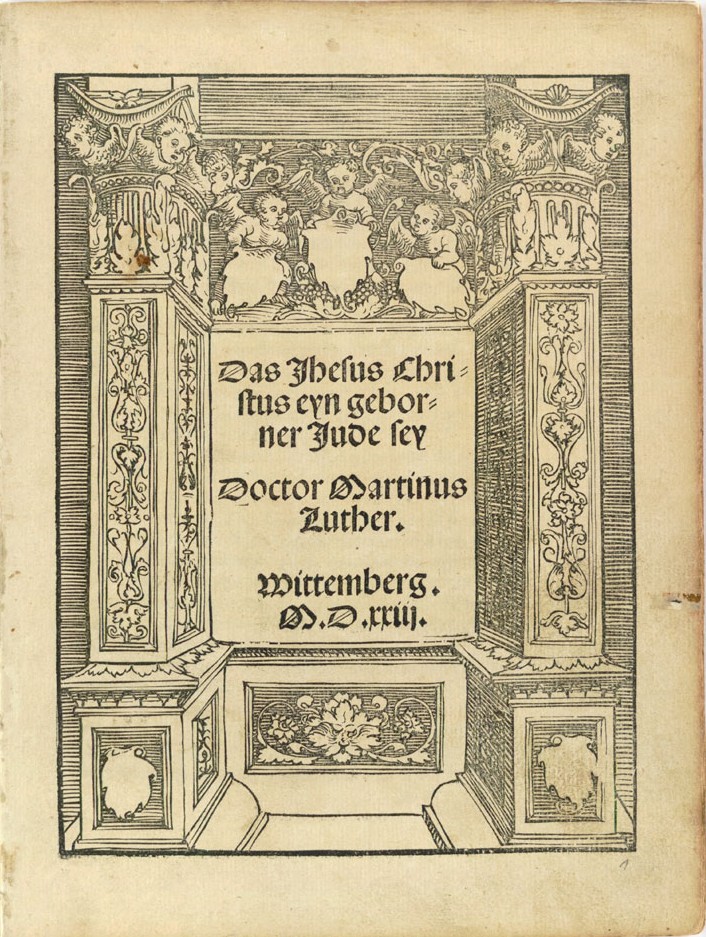

Title-page from That Jesus was Born a Jew 1523, text by Martin Luther and illustrations by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt

Up until this point Wittenberg imprints had mostly been associated with the spare utilitarian texts of Rhau-Grunenberg. Printers outside Wittenberg had improved the look somewhat, using decorative borders to frame the title. Cranach offered a radically new solution: a title-page frame, made up not of separate panels but a single woodcut. Here the illustrative features were blocked around a blank central panel into which the title could then be inserted. It was a masterpiece of design innovation, solving a complex problem of integrating text and decorative material while allowing space for imaginative artistic expression on the front of the book. It was a major and decisive breakthrough in the history of the book, and for the Reformation. Cranach’s exquisite work now adorned pamphlets that might sell for no more than a few pence. Stylistically this was the part of Cranach’s artistic oeuvre that most self-consciously adhered to the principles of Renaissance art. A statement was being made: the message of the Reformation – Luther’s message – deserved to be magnificently arranged. In the process, and thanks to Cranach’s decisive intervention, the Wittenberg book led the way in terms of aesthetic appeal.

The distinctive look provided by Cranach’s title-page designs was the final component of a puzzle that had been taxing Germany’s printers since the early days of the Reformation: how to capitalise on their most marketable property, the new phenomenon that was Martin Luther. In the design of the Reformation title-page we also see printers gradually waking up to the potency of Luther’s personal reputation as a writer and teacher. Early works often bury Luther’s name in the midst of a dense block of text; not infrequently his name is split over two lines (Lu- / theri), if that is what is dictated by the blocking. This obscured the book’s most obvious selling point, which printers soon recognised. They learned to move Luther’s name on to a line of its own, separated from the main body of the title. The name is often in a bold type of larger size, intended to spring off the page to catch the eye of purchasers surveying a mass of titles piled up on the bookseller’s stall.

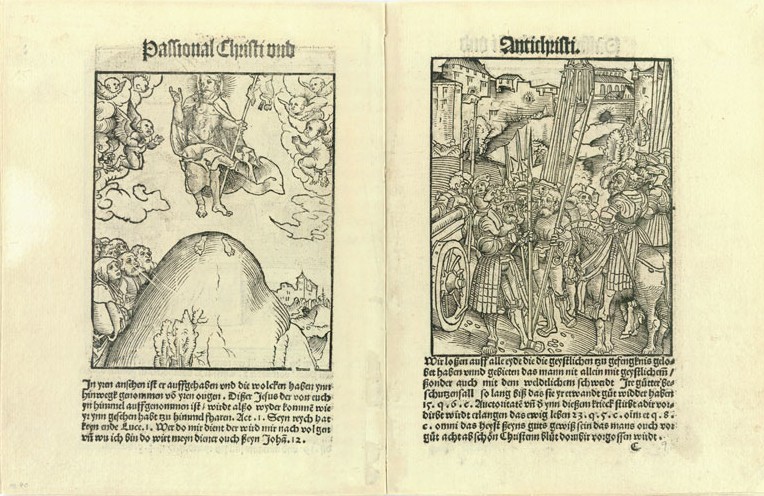

Passion of Christ and Antichrist 1521, texts by Philip Melanchton and Johannes Schwertfeger; illustrations by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt

The last element of brand identity was Wittenberg itself. In most parts of Europe it was now common practice for the printer’s address to be printed in neat small type at the bottom of the title page. Not so in Wittenberg. Here the printer’s name was mostly relegated to the end (the colophon) or omitted altogether. Instead the city was given pride of place, often on a single line at the bottom, separated from other text by several centimetres of white space.

Of course there were other images: the Passion of Christ and Antichrist (1521), a pictorial encapsulation of the Protestant reason for rejecting the Pope, created in partnership with Melanchthon, and the Law and Grace, a powerful representation of the old and the new law, and developed by Cranach both as a painted panel (1529) and as a book title-page (1528). Cranach’s other signal service to the Reformation was the fashioning of the portraits of Luther that first made his physical features known beyond the relatively narrow group of those who had encountered him in person. The initiative for the first portrait – an engraving – seems to have come from Albrecht Dürer. A passionate admirer of Luther from his first reading of the preacher’s works, Dürer regretted the lack of a true likeness of the reformer. He wrote suggesting such a likeness be created, enclosing copies of his magnificent portrait of Albrecht of Brandenburg as a model. Cranach studied the portrait of Albrecht carefully before embarking on his own rendition of Luther. The result was a triumph, simultaneously a magnificent propaganda piece and a lifelike rendering of the reformer at a seminal moment of his career (1520). Cranach depicts Luther as a simple monk, lean but not gaunt, staring impassively outward, resolute and monumental in the face of adversity: the simple man of God strong against the marshalled forces of the institutional church.

Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk (1520), Lucas Cranach the Elder. Thrivent Financial Collection of Religious Art, Minneapolis

This image was not destined for immediate circulation. In the months before Luther’s appearance at the Diet of Worms in 1521, many at the Elector’s court feared that this portrait of heroic resolution might strike the wrong note. Asked to respond, Cranach produced a second image that, while capturing Luther’s inner essence in the same way, gives the appropriate hint of humility. Luther, now shown within a wall niche, places a hand across his heart in a traditional sign of friendship and sincerity; in his other hand is an open book. Once again he wears the monk’s habit. The impact of these images, and of unauthorised images with less iconographic fidelity, is clearly attested by contemporary witnesses. But Luther also played his part in establishing his own celebrity. We know this from a fascinating little vignette in an otherwise routine letter to Georg Spalatin in early March 1521, while Luther was awaiting his summons to the Diet of Worms. With this letter he enclosed some copies of Cranach’s early engraved portrait of himself, which at Cranach’s request he had also autographed.

Luther understood his own importance to the Reformation’s extraordinary success. Although he mused in his letters and sermons on his role as the humble instrument of God’s purpose, he was fully aware that his own personality and the drama of his struggle with the church authorities was what had piqued public interest, and had furnished the movement with its most powerful shield against those who would destroy it. This undisguised self-knowledge was a key aspect of Luther’s movement which, in partnership with Cranach’s artistry and exceptional business competence, played a major part in its success.

Luther Exhibitions USA 2016 project: ‘Word and Image: Martin Luther’s Reformation’ at the Morgan Library and Museum, New York (7 October–22 January 2017); ‘Law and Grace: Martin Luther, Lucas Cranach, and the Promise of Salvation’ at Pitts Theology Library, Emory University, Atlanta (11 October–16 January 2017); and ‘Martin Luther: Art and the Reformation’ at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (30 October–15 January 2017).

From the October issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.