Famous for declaring to Congress in 1949 that ‘all modern art is communistic’, and warning that the social fabric of postwar American life was under threat from modernist experimentation, the Republican Senator George Dondero later defended his position in an interview with art critic Emily Genauer: ‘modern art is Communistic because it is distorted and ugly, because it does not glorify our beautiful country, our cheerful and smiling people, our material progress. Art which does not glorify our beautiful country in plain simple terms that everyone can understand breeds dissatisfaction. It is therefore opposed to our government and those who promote it are our enemies.’

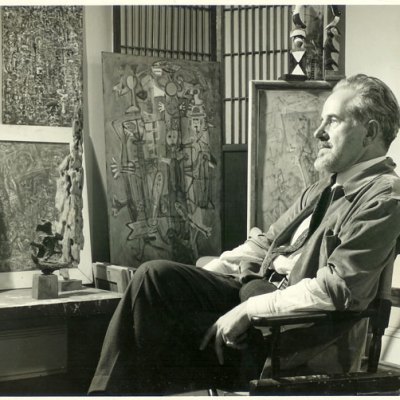

It is a statement with not a little historical irony. First, this kind of anti-intellectualism and open disdain for modernist form on the grounds that it did not adequately represent the realities of life for working people was a common doctrine of various European Communist Parties. And within what became the cultural Cold War, the official history goes that the CIA and other agents of the liberal American establishment, both governmental and private, had decided that modern art was in fact a rather good weapon with which to parry – and even slay – Soviet propaganda. Compared to the doctrinaire social realism of the Russians, the Americans had the vital energy of Pollock and de Kooning, a fierce gesturalism that might express the anxieties of being a modern man in an uncertain world. For this narrative, it did not matter too much that almost all of the artists ultimately promoted by the CIA had been on the left in their early careers, or that some of them most certainly still were, because the freedom of speech and life under capitalism could accommodate, and even celebrate, dissent. Far from being an obstacle to promoting liberal values in the Cold War, modern art soon became its strongest symbol.

It is this story in general, and that of the activities of the CIA-backed Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) in particular, that is the focus of the exhibition ‘Parapolitics: Cultural Freedom and the Cold War’, held in the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin. In many ways, ‘Parapolitics’ is an intellectually robust show that deals with lots of archival material with a deft and inviting touch. We begin in a room mostly interested in the history of exhibition-making in the post-war period, as Western Cold War ideology seeped into even the most innocuous art fair or small magazine. One wall tells the story of Ad Reinhardt’s restrained black paintings, and his complex attitude to socialist aesthetics and abstraction, with audio accompaniments by the likes of Frances Stonor Saunders, a historian who has done much to uncover the institutional complicities between Abstract Expressionists and the CIA during the Cold War.

‘Parapolitics: Cultural Freedom and the Cold War’, installation view at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 2017. © Peter Adamik/HKW

However, in wanting to show the kinds of artworks displayed in certain exhibitions, the exhibition disappoints a little. The featured paintings of the 20th century’s modernist masters are copies, in uneven degrees of likeness to the (admittedly exorbitant-to-loan) originals, and this distraction might have meant it was better not to have shown them at all. (It is a cruel irony that the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, formerly West Berlin’s Kongresshalle, was once just the kind of art institution supported by the deep pockets of the American government and Atlanticist philanthropists – now, with the Cold War over, it is not.)

The next space, twice the size, addresses artistic-political issues as many and various as Alfred Barr’s teleology of modernist art; Norman Rockwell’s nostalgic Four Freedoms series from 1943, inspired by President Roosevelt’s State of the Union Address in 1941; and first editions of George Orwell’s Animal Farm and Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon, two anti-totalitarian handbooks implicated in various ways in the enterprises of the CCF and CIA.

Here, too, we encounter footage of the Dialectics of Liberation Congress in 1967, and the extraordinary slogging match that ensued when a self-defined ‘white liberal’ asked Stokely Carmichael, philosopher-firebrand of the Black Panther movement, whether he really had a rifle after a debate on political violence. Visibly enraged, Carmichael asks ‘What have you done?’ over and over, forcing the predominantly white, pacifist audience to ruminate on their own culpabilities in perpetuating racial violence. An exasperated, politically exposed Allen Ginsberg sits beside Carmichael, apparently in prayer.

The sheer scale of collated material is both the exhibition’s achievement and, at times, its shortcoming. The initially clear and urgent aim, to tell the story of the CCF with the visual and audio documents that made it such a compelling instrument as a kind of Marshall Plan in the field of ideas, begins to dissipate as the show expands to explore any and all things touching on ideology in the second half of the 20th century. We might wonder what connects some of this archival material, or whether an exhibition and not a monograph is actually the best way to piece all these sources together.

Stalin by Picasso or Portrait of Woman with Moustache Façade-banner (2008), Lene Berg. Courtesy of the artist

But with these questions out of the way, I want to conclude with one of the sure joys of the exhibition: Norwegian artist Lene Berg’s clever and witty Stalin by Picasso, or Portrait of a Woman with Moustache (2008). In this 30-minute video, assembled like a children’s book with its flaps and openings, cut-out newspaper clippings and old photographs, we follow the composition of, and fallout from, Picasso’s portrait drawn on the death of Stalin in 1953. Reprinted on the front page of an issue of Les Lettres Françaises at the request of Surrealist poet Louis Aragon, Picasso’s sketch (knocked up in just a few minutes, according to Françoise Gilot) depicts a youthful Stalin looking at us. His hair is pulled back, as though in plaits; his moustache is unruly and unkempt; his eyes uncertain. Members of the Secretariat of the French Communist Party were appalled and, while grateful for the support of the most famous painter of the day, they did not think that his depiction sufficiently honoured the great leader.

Picasso’s portrait was not reverential enough, which is to say that it did not conform to the cult of personality scaffolded around Stalin at the time of his death. But the outrage also pointed to wider questions around form and ideology: how political commitment is represented (or not) by a particular style, such as the realism favoured by the Communist Party. Tom Braden, the CIA agent who assembled the International Organizations Division, famously said that the Cold War was in essence ‘the battle for Picasso’s mind’, so great was his standing among both the American and European intelligentsia. But what this obscure scandal also demonstrates is that when it came to perceived representations of political ‘reality’ and order, or to the cultural manoeuvrings under the Cold War, then perhaps the French Communist Party and the Donderos of McCarthy’s America were not as far from one another as they would have you believe.

‘Parapolitics: Cultural Freedom and the Cold War’ is at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, until 8 January.