An exhibition, titled ‘Print Rebels’, recently opened at Bankside Gallery in London, celebrating the surgeon and etcher Francis Seymour Haden. Now almost forgotten, in 1880 Seymour Haden founded the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers and, together with his American brother-in-law Whistler, launched the Etching Revival in Britain. The enthusiasm for prints among artists and collectors persisted right up until the Great Depression of 1929. The interwar period witnessed the final flamboyant flowering of this strong tradition of British printmaking – and also its demise. And yet, despite the collapse of the market in 1930, printmaking persisted in all its many varieties, from the abstract linocuts of Ben Nicholson to the evocative lithographs of Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious.

It was not until the 1980s that market interest in prints of this era began to revive. Over the last 10 years certain printmakers and schools – C.R.W. Nevinson, Paul Nash, Edward Wadsworth, the Grosvenor School – have witnessed a huge surge in prices, while others have remained neglected. But as artists of that generation are gradually rediscovered (this summer Bawden is honoured with a major survey at Dulwich Picture Gallery, following the hugely popular exhibitions of Ravilious in 2015 and Nash in 2010) it is likely that their prints too will be newly appreciated.

Gordon Cooke, a 19th- and 20th-century prints specialist and private dealer, tells me that during the 1920s, ‘print collecting became a mania’. Artists who had made their names forging a visual language to articulate the horrors of war – such as Nash and Nevinson – looked for solace in landscape and nature or in the hopeful energy of city life in the Roaring Twenties. Figures such as Gwen Raverat, Clare Leighton, Graham Sutherland, Paul Dalou Drury and Robin Tanner developed a distinctly British pastoral tradition of prints that looked to Thomas Bewick, William Blake and Samuel Palmer before them. Prices were rising so fast, says Cooke, that ‘an artist would make a new print, the gallery would invite collectors to subscribe, collectors would then book an auction sale six months down the line and flip their impression from the sold-out edition’. Alongside the etchers and engravers, the Grosvenor School of Modern Art, a private art school established in 1925 by wood engraver Iain Macnab, pioneered the new technique of linoleum cutting. Claude Flight, who ran the school with Macnab until 1930, was an advocate of this cheap and democratic medium. He taught many of its leading figures – Sybil Andrews, Cyril Power, Lill Tschudi and the Australian Ethel Spowers – encouraging a bold, futuristic style. And then, says Cooke, ‘the market stopped. In 1929 Robin Tanner sold out. In 1930 he sold one print.’

Two Black Bows (1932), Ethel Gabain. Gordon Cooke, £950

The names of those most sought after in that period, he continues, ‘the Scottish etchers Muirhead Bone, David Young Cameron and James McBey, are now almost forgotten’. Sutherland turned to painting, Tanner to teaching. Cooke represents the estates of John Copley and Ethel Gabain, both prolific and committed printmakers beyond 1929, and has exhibited their work since 1985, most recently last year at the Fine Art Society. ‘I think Gabain is having a new lease of life,’ he says. ‘Of the 38 prints in last year’s show, I’ve sold nearly all. People respond to her emotional power.’ He is taking works by both (£950–£1,900) to the London Original Print Fair (LOPF; 3–6 May).

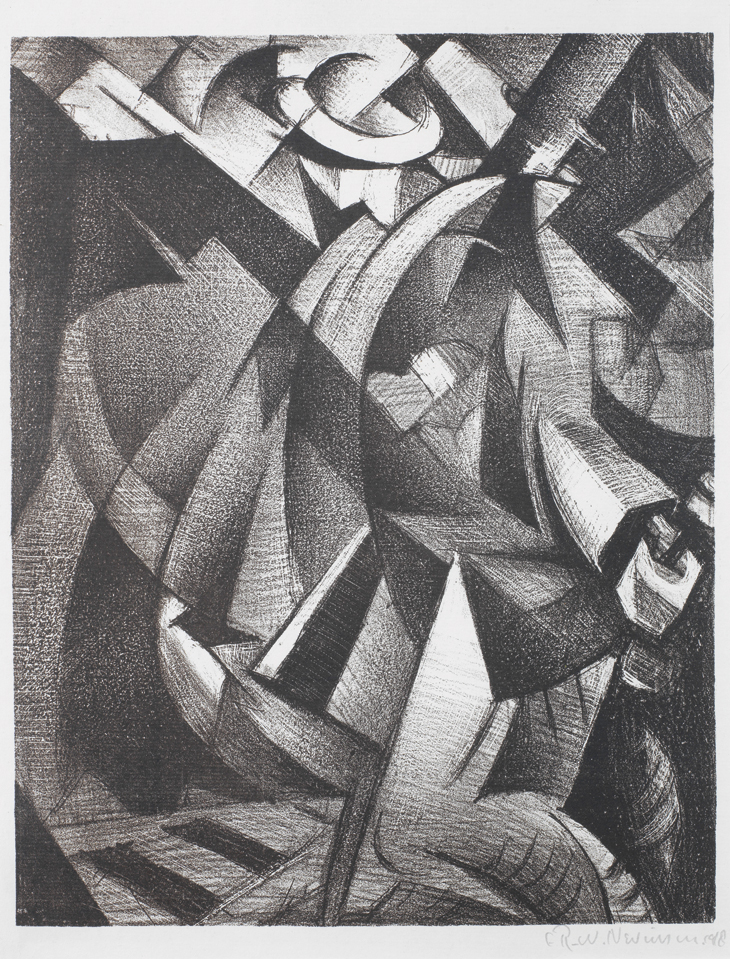

Bomber (1918), C.R.W. Nevinson. Bonhams, £109,250. Courtesy Bonhams

Gordon Samuel of dealership Osborne Samuel favours prints that express the beginnings of modernism: those of Edward Wadsworth (associated with the Vorticists), Nevinson, Nash and William Roberts. Their wartime prints fetch by far the highest prices. Wadsworth’s radical geometric prints are hard to find. In 2012, his 1918 woodcut, S.S. Jerseymoor (Colnaghi catalogue 130), fetched £73,250 at Christie’s London. Hot competition for Nevinson’s wartime prints between a small number of American collectors saw his prices soar between 2010 and 2014. In March 2012, his 1917 lithograph, Building Aircraft: Banking at 4000 Feet, achieved £115,250 at Sotheby’s London – a month later £109,250 was found at Bonhams for his rare lithograph of the following year, Bomber.

Samuel confirms that the Americans have been strong collectors in this field; Europeans are less interested, although they value the prints of Henry Moore and Nicholson. He also reports that the market for radical printmaker Stanley William Hayter is ‘very soft’. This is confirmed by Richard Gault of the Redfern Gallery, who is taking prints by Hayter and Anthony Gross to LOPF. ‘Interwar prints by both Hayter and Gross remain affordable considering their exceptional quality and importance,’ he says. More sought after, according to Samuel, are ‘Edward Burra’s prints from the early 1930s, Nicholson’s early linocuts and Ravilious’. He is bringing a rare Matissean lithograph by Vanessa Bell to LOPF (The Schoolroom of 1938; £4,500) and next year will mount a Grosvenor School exhibition. Meanwhile, another 20th-century specialist, Piano Nobile in Holland Park, has some Paul Nash prints from between the wars (£4,000–£8,000). Director Matthew Travers comments: ‘The most popular from this period are his wood engravings – the Genesis series [1924], for instance, and Design of Flowers [1926].’

The Schoolroom (1938), Vanessa Bell. Osborne Samuel, £4,500

The Grosvenor School is a whole market of its own, and the Redfern Gallery has championed the work of Flight and his students since 1929. ‘After a long period of almost complete obscurity, the linocuts re-emerged in the early 1980s with exhibitions at Michael Parkin and the Redfern,’ says Gault. ‘Over the past 20 years demand for British colour linocuts of the twenties and thirties has increased dramatically as major collectors (mainly in the UK and United States) began to acquire them. Today they are among the most popular images in British printmaking.’ The Redfern Gallery exhibits a strong selection at LOPF, although, Gault comments, examples ‘are becoming increasingly difficult to find’.

Yessica Marks, a print specialist at Sotheby’s, recalls how in 2011 Power’s linocut, The Merry-Go-Round, c. 1930, soared to £32,450 on a £5,000–£7,000 estimate. ‘This was the start of the boom,’ she says. ‘We had sold the same print in 2002 for £2,000.’ In 2012 Flight’s Brooklands sold for £79,250 on an already ambitious estimate of £25,000–£35,000. The peak was reached in 2012 when a fresh impression of Spowers’ linocut, The Gust of Wind (1930–31), achieved £114,050 against an estimate of £15,000–£20,000 at Bonhams.

Speedway (1934), Sybil Andrews. Sotheby’s London Courtesy Sotheby’s; © The Estate of Sybil Andrews, Glenbow, Calgary, Canada, 2018

Since 2015 prices have cooled off. Even so, a trial proof of Andrews’ elegant 1934 linocut, Speedway, fetched £60,000 against an estimate of £35,000–£45,000 at Sotheby’s London last April. Condition matters. But, as Marks says: ‘Collectors are drawn to the handmade aesthetic of these prints.’ In a further sign of continuing interest in the field, four dynamic linocuts by Walter Greengrass (dated 1933–35), a lesser-known member of the school, made a total of £39,700 at Lawrences in Crewkerne in January, with the top price of £14,640 paid for Seaside Morning (1935).

‘Print Rebels’ is at Bankside Gallery, London until 13 May. The London Original Print Fair is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, from 3–6 May.

From the April issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.