Early editions of The Jungle Book and other Indian stories by Rudyard Kipling – those with an elephant’s head with a swastika embossed on the red cloth boards – were illustrated with vignettes, many like sculptured friezes, signed ‘LK’. They were the work of the writer’s father, John Lockwood Kipling (1837–1911), to whom tribute was paid in Kim when he was described as the Curator of the ‘Wonder House’, that is the Victoria Jubilee Museum in Lahore (with the famous Zamzama Gun in front), which he had not only augmented, but partly designed. Lockwood Kipling had gone out to India in 1865 (where and when Rudyard was born) to teach modelling, terracotta and architectural sculpture at the recently established Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy School of Art in Bombay. A decade later he became the principal of the Mayo School of Industrial Art in Lahore, eventually retiring and returning to England in 1893. Hence Rudyard’s knowledge of the ancient Muslim city where he began his career as a journalist.

Lockwood Kipling with his son Rudyard Kipling in 1882. © National Trust/Charles Thomas

Lockwood Kipling was a sculptor, draughtsman, teacher, journalist, conservationist, and a hugely important promoter and defender of the traditional arts and crafts in India, yet his reputation has for long been eclipsed by that of his more famous son. His work, and that of his pupils at the School of Art, will be known to any visitor to modern Mumbai interested in its incomparable Victorian buildings. It will also be known to the visitor to Osborne House on the Isle of Wight where, in 1890, Queen Victoria – unable to visit the India that entranced her and by now infatuated with the Munshi – commissioned Kipling and his architect pupil from Lahore, Bhai Ram Singh (1858–1916), to fit out the Durbar Room with Punjabi carved wood decoration. The Queen was delighted: ‘The effect is quite lovely, & quite unique in Europe.’ Yet only now, with an exhibition, appropriately at the Victoria and Albert Museum (14 January–2 April), and a superb, comprehensive, and well-illustrated catalogue edited by Julius Bryant and Susan Weber (Bard Graduate Center/Yale University Press), has full justice been done to the achievement of this remarkable but self-effacing man and artist.

Durbar Hall at Osborne designed by Bhai Ram Singh and Lockwood Kipling in 1890. Bard Graduate Center New York/Bruce M. White

Born in 1837, the son of a Wesleyan minister, Kipling – like so many – was introduced to and inspired by the arts of India by visiting the Great Exhibition of 1851 (so unlike his slightly older contemporary, William Morris, who refused to go inside the horrid iron and glass building). Kipling’s artistic training was in ceramics in the Potteries, in Stoke-on-Trent, before he began to work as a sculptor, acting as assistant to John Birnie Philip. Kipling’s hand, therefore, may be evident in several buildings designed by George Gilbert Scott which have architectural carving by Philip, notably Exeter College Chapel, Oxford; All Souls’, Haley Hill, Halifax (‘on the whole my best church’) and the transmogrification of Wren’s St Michael’s Cornhill. Kipling then moved on to the Department of Science and Art in London, where he assisted Godfrey Sykes on terracotta decoration of the South Kensington Museum. In 1863, Kipling, together with the architect Robert Edgar, secured first prize in a competition to design the façade and ceramic decoration on the proposed Wedgwood Memorial Institute at Burslem back in the Potteries, but did not execute any of the work owing to his departure for Bombay two years later.

Kipling’s decision to take up a post at the Bombay School of Art (along with the painter, John Griffiths) may well have been the result of a crucial event in his life: his marriage that same year, 1865, to Alice Macdonald, one of seven daughters of another Wesleyan Methodist minister. They had met on a picnic at Rudyard Lake in Staffordshire (hence the unusual name of their first born). Alice was a poet and a forceful character in her own right – one Viceroy of India, Lord Dufferin, would remark that ‘Dullness and Mrs Kipling cannot exist in the same room’; others, perhaps victims of the Kiplings’ cleverness and wit, were hostile, one critic writing to his wife in Simla, ‘I quite agree with you about their intelligence, but I think they are both horrid cads.’ By marrying Alice, Kipling became more closely connected with the London art world and with the burgeoning Arts and Crafts movement, for he acquired as brothers-in-law the painters Edward Burne-Jones and Edward Poynter. Another brother-in-law was the Worcestershire industrialist Alfred Baldwin, enabling Rudyard Kipling to have a future Prime Minister as his cousin.

Rudyard was born in temporary buildings erected on the Esplanade in Bombay for the Sir J.J. School of Art. Eventually permanent, Gothic Revival buildings were erected, designed by George Twigge Molecey, but Kipling had left for Lahore before they were completed. Bombay might have been able to boast a building designed by William Burges, who, in 1866, sent out 129 sheets of drawings for a new School of Art – the ‘most marvellous design that he ever made’ – but, typically, it proved too expensive to build. The drawings were taken to Bombay by Burges’s assistant William Emerson, who would soon give Kipling an opportunity to demonstrate his skill as a sculptor when he won the competition for the new Crawford Market. Two tympanums, carved by Kipling and his students, embellish the curved corner of this fine Gothic building and depict the activities of the market. Emerson also designed two elaborate and ponderous Burgesian fountains, which were also embellished by Kipling and his team.

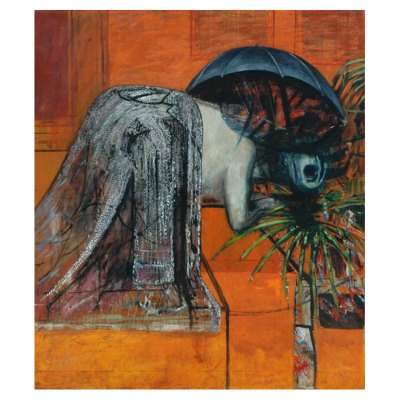

Tympanum in Crawford Market, Bombay, depicting trade in India, carved by John Lockwood

Kipling and his students in c. 1869–71. Photo: © Siddharth Pandey

Many of the Gothic Revival buildings in Bombay benefitted from Kipling’s department at the School of Art. The Convocation Hall of the university, built from a (modified) design sent out by Gilbert Scott, sports lively capitals in the interior, with animals and foliage framing carved heads, although the carving on the Library was carried out by a native rival, Rao Bahadur Makund Ramchandra. In all, some 50 new Bombay buildings had carving – including portrait heads, modelling and ironwork, carried out by Kipling and his students. In 1874, the Times of India reported that these results show ‘that the teaching power having been secured by the acquisition of Mr. Kipling and the other professors of the Sir Jamsetjee School of Art, native workmen have been apt to learn as their confrères in Europe and that architecture has now […] a glorious future before her in India’. The previous year, Colonel H. St Clair Wilkins, architect of the Secretariat on the Esplanade, wrote to Kipling: ‘I consider you were the pioneer of your art in this country; for, eight years ago, when I first met you, artistic sculpture of natural objects was unknown in India. In 1863 an architectural design of mine was said […] to be “out of the question” owing to the introduction of foliated capitals. In 1865, you had, I believe, performed that which in 1863 had been pronounced impossible.’

What was discouraging for Kipling was that, for formal portrait sculpture, statues by well-established artists continued to be sent out from Britain. For instance, with the David Sassoon Library, while the portrait bust of the great Parsee benefactor on the entrance porch was carried out by Kipling, the full-size marble statue inside was by Thomas Woolner. This may well be why, after his translation to Lahore in 1875, Kipling executed little sculpture and, as well as becoming fascinated by Gandharan sculpture, concentrated much more on encouraging the traditional arts and crafts, increasingly threatened by the import of industrial products from Britain. This, indeed, had been part of the mission of the Department of Science and Art back in London, which controlled the curriculum of the Bombay School of Art and the other schools in Calcutta and Madras. And Kipling himself, while still in Bombay, began to visit villages and study the work of native craftsmen.

In Lahore, Kipling was both principal of the Mayo School of Art and curator of what was then called the Central Museum (sadly, the collection he helped build up is now split between Lahore, now in Pakistan, and Chandigarh in India). He announced that, ‘It is the object of the Lahore School to revive crafts now half-forgotten, and to discourage as much as possible the crude attempts at reproduction of the worst features of Birmingham and Manchester work now so common among natives.’ This he achieved both through the teaching in the school and by his energetic work in showing traditional Indian craftsmanship at exhibitions. Kipling was instrumental in contributing India work – textiles, sculpture, metalwork, carving, and much else – to 28 national (Indian) and international exhibitions, in Glasgow, Paris, Melbourne, and elsewhere, including the Colonial and Indian Exhibition held in London in 1886. He also arranged for casts to be made of ancient sculptures and buildings and sent to London for the Cast Courts in the South Kensington Museum, then being assembled.

Among his many other activities, Kipling found time to establish and contribute to the Journal of Indian Art, whose first issue appeared in 1884. This both promoted Indian crafts and encouraged the preservation of historic buildings in Lahore and elsewhere. But, as Kipling himself recognised, these efforts could not have achieved success in isolation. At his farewell dinner in Lahore in 1893, Kipling spoke about the ‘improvement of Indian art’ and ‘a better appreciation of Indian art’ and argued that his efforts in these directions would have been fruitless if they had ‘not been contemporary with a general movement all through English society in a similar direction’. In fact, Kipling was trying to achieve in India what William Morris was encouraging back home: he may be regarded as a British Indian exponent of the Arts and Crafts movement.

The enemy, in so much of his work, was officialdom in the shape of the Public Works Department. In an article on ‘Indian Architecture of To-day’ in the Journal of Indian Art in 1886, Kipling complained that a typical PWD building – ‘bungaloathsome’ – was ‘a long low wall pierced with round-headed cavities, entirely without architectural sense of mass, with no distinguishing features and no details to speak of […] There are hundreds of such buildings in India, where, cut up into larger or shorter lengths, they serve for law courts, schools, municipal halls, dak bungalows, barracks, post offices, and other needs of our high civilisation.’ There was, however, an alternative, which Kipling illustrated and encouraged. In Bulandshahr, the PWD architect F.S. Growse used local builders and craftsmen to create buildings and bridges in a traditional style – until he was summarily posted elsewhere for being so enlightened.

Bhai Ram Singh, (1892), Rudolf Swoboda. © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016

Interest in traditional methods and working with architects led Kipling to try architectural design himself. At the Imperial Assemblage or Delhi Durbar of 1877, at which Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India by the Viceroy, Lord Lytton, Kipling designed the amphitheatre and other structures. And in Lahore, Kipling’s vision of a cultural quarter necessitated new buildings for both the School of Art and the Museum. These were designed by Kipling working with a former pupil, Bhai Ram Singh, ‘our most accomplished architect’. Kipling argued that, ‘A building intended to be used as a school of instruction in Oriental art and for the exposition of its best works should be conceived and designed in an Oriental spirit.’ The result was several early essays in what came to be called the Indo-Saracenic Style, an eclectic fusion of Western planning and Indian motifs which, in the 1880s, evolved out of the Gothic Revival in India and whose principal exponent was Sir Swinton Jacob. And, thanks to Royal patronage, Kipling, with Ram Singh, created examples back in Britain: not only the Durbar Room at Osborne, but also the billiard room at Bagshot Park for Queen Victoria’s son the Duke of Connaught, who knew India well.

Concern for India’s traditions did not, however, mean that Kipling had any sympathy for Indian aspirations for self-government. Like his son, Lockwood Kipling was essentially a conservative imperialist with typical racist views – one reason, perhaps, why it has taken so long to recognise his positive contribution to India. He may have been interested in protecting the peasant craftsman, but he disliked the rising middle class in India – ‘the new man, with great fluency, boundless bumptiousness and no manners’. He was happy to advocate ‘severe repression’ when necessary and argued that the climate of the subcontinent was ‘destructive of the qualities that lead to moral excellence, mental energy and the highest development of physical power’.

In the end, neither Kipling nor the wider Arts and Crafts movement could stem the exploitative and deleterious effects of British colonial rule on the economy of India. Gandhi may have taken up weaving in protest at British commercial dominance, but these crafts were very basic: he had no interest in the refined aesthetics of traditional Indian sculpture and carving, weaving, and textiles that Kipling had. Nevertheless, as Abigail McGowan concludes, ‘Those who work to ensure the survival of traditional crafts and the economic viability of artisanal work […] share admiration for India’s craft heritage, deep knowledge of local practises, interest in adapting to new markets, and commitment to educating both producers and consumers alike – all principles embraced in the late nineteenth century by John Lockwood Kipling.’

This exhibition, an exemplary tribute to this most energetic Victorian, offers several surprises. One is that Kipling’s last work of art was a sculptured relief panel on the Honoured Dead Memorial at Kimberley in South Africa, a powerful classical composition by Herbert Baker which was the harbinger of the imperial classicism which triumphed at New Delhi – to the dismay of Kipling’s disciple, E.B. Havell, head of the Madras School of Art. Another is his friendship with the woman who, after his death, would become the famous society interior decorator Sibyl Colefax. She was the daughter of Mrs Sophie Halsey, to whom Kipling, when alone in India, became close. The five-year-old Sibyl first encountered Kipling during the social whirl in Simla, the summer capital, in 1879 and later recalled that he had ‘the head of a philosopher, & the bluest eyes I ever saw & a vast beard’ and that he was ‘the only one who was real’. Later, when she was Mrs Colefax, he advised her to paint the interior of her London flat white.

Simla was a retreat from Lahore, where Kipling’s health eventually broke down – he once wrote that ‘On a hot night there is no more fearful place in the world than Lahore. It is hell with the lid on.’ As for his son, that tortured imperialist who left India, never to return, in 1889 and who today somehow seems less real and less pleasant (he destroyed his father’s private correspondence after his death), Rudyard Kipling later recalled Lockwood once saying in Lahore that, ‘If you get simple beauty, and naught else, you get about the best thing God invests.’ He then went on to write, ‘And so much for Kim which has stood up for thirty-five years. There was a good deal of beauty in it, and not a little wisdom, the best in both sorts being owed to my father.

‘Lockwood Kipling: Arts and Crafts in the Punjab and London’ is at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, from 14 January–2 April.