A smooth hawthorn pole with a hand mirror hanging from it marks the beginning of ‘Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World’, alongside a piece of yellow canvas painted with a text on sacred trees – an Ahuahuete in Mexico, an Irish yew, and a magnolia in Arkansas, where the artist was born. ‘Be warned,’ reads the text, titled Anti Flag (1992), ‘a moveable pole cannot support the center of the world, only trees can.’ Neither the height of the pole (one of his series A Pole to Mark the Center of the World, followed by wherever he is working) nor the size of the unstretched canvas seem proportional to the exhibition’s apparently grandiose title. Indeed, throughout the 120 works of Durham’s first retrospective in America, which span sculpture, video, collage, and drawing, expected artistic gestures are set up, only to be contradicted or given a punch line.

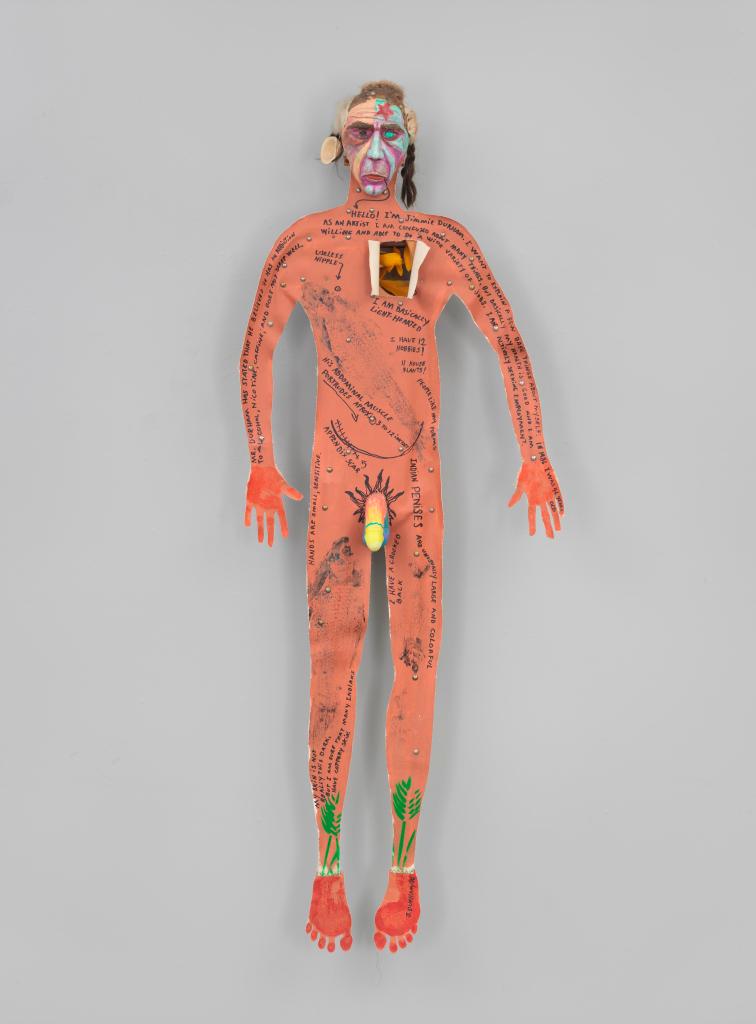

Self-portrait (1986), Jimmie Durham. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

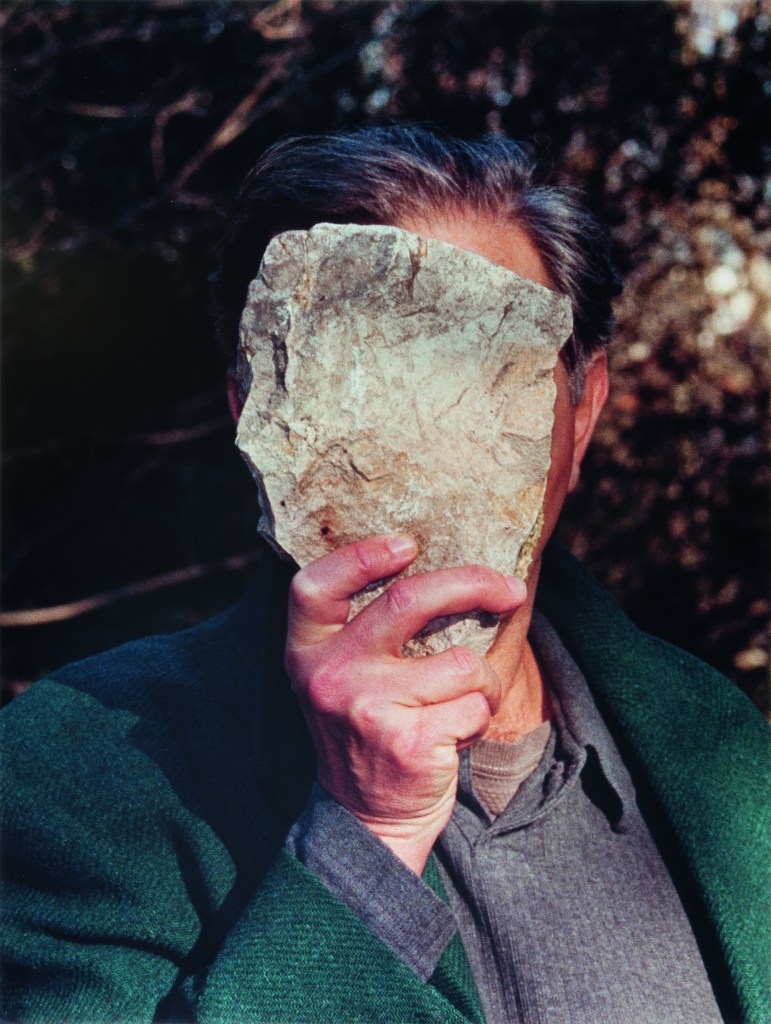

Invited to participate in 1986 in a show of self-portraiture at Kenkeleba, a non-profit space on the Lower East Side, Durham made a life-size cut-out of ‘himself’. The copper-coloured body is labelled with writing in a capitalised hand. The words represent the persona, that of an unreliable narrator or cynical entertainer, which Durham has adopted for the last 30 years to tell jokes, warn about interpretation, and mimic indigenous stereotypes. In this early Self-Portrait, where the heart should be are the words: ‘I am basically light hearted’; and down the leg: ‘Indian penises are unusually large and colourful.’ When I visit, a child holding her father’s hand finds the painted wooden appendage very funny. Writing in another voice, posing as the expert or anthropologist, comments: ‘Mr. Durham has stated that he believes he has addictions to alcohol, nicotine, and caffeine.’ In a self-portrait later in his career, Pretending to Be a Stone Statue of Myself (2006), he knowingly performs the role of the immortalised artist, face hidden.

Self-portrait pretending to be a stone statue of myself (2006), Jimmie Durham Collection of fluid archives, Karlsruhe. Courtesy of ZKM Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe

Durham has rejected identity categories throughout his life and practice, but there are ongoing debates as to whether his work should be discussed in the context of Native American art. He once claimed Cherokee ancestry, though he is not officially recognised by any of the three Cherokee Nations; left America for Mexico in 1987, and Mexico for Europe in 1994. He began to make art after becoming disillusioned with his organising work for the American Indian Movement (AIM) in New York in the 1970s, turning instead to critiques of colonial history, its narratives and institutions, via sculptural assemblages. In Tlunh Datsi (1984), for example, the triangular frame of a blue police-barrier is headed by an open-mouthed panther skull decorated with feathers and deer fur, as though in ‘Indian’ headdress; roaring against the establishment, the sculpture could be a call to, or away from, arms. ‘I do not feel that ‘America’ has any right to either name me or un-name me,’ he has said.

Tlunh Datsi (1984), Jimmie Durham. Private collection

Mainly, Durham’s project is to subvert signs of authenticity and condemn the desire for mastery – of identity, knowledge, language, and peoples. His humour – communicated in the aforementioned notes, in titles (New Clear Family), as well as in visual puns, such as Footnote (1989), a brass foot with an absurdist note attached – is a match for his defiance. Indeed it could be said that his wit, along with his curiosity about materials, enables his very passage into the systems and spaces of contemporary art.

Durham criticises Western classificatory systems in The Dangers of Petrification II (1987–2007), in which he collects various stones that resemble food – black bread, striated mortadella, crystallised cheese – and names them as petrified specimens. A cynicism towards the assumed objectivity of science is sketched in a series of naive-looking graphite drawings and their titles: The Turquoise Line Is Probably Indicative (1990), Recalcitrant Trends (2013). St. Frigo involves a ritual of throwing stones at a fridge for a week, a process documented in the video Stoning the Refrigerator (1996). The dented ex-machine is displayed opposite the latter; less durable than stone, perhaps, but for now safely elevated to the status of art.

Without the wit, it would all seem like a scathing (if necessary) take-down. But the impression of the exhibition as a whole is of an expanded perception of the world. Omniscient narratives are not to be trusted, but the stories lodged within materials unlock localised knowledge and an enchantment with what lies beneath the surface of things. Durham’s work is aware of being hung from a white wall, in whichever art-world hub holds itself at the heart of what is happening, yet it extends a generous invitation to the viewer to step out of their centre.

‘Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World’ is at the Whitney Museum of American Art until 28 January 2018.