On a circular stand, in a corner room of the new Musée Camille Claudel, there are four versions of La Valse (The Waltz), a work that Claudel (1864– 1943) began in 1889 and which reflects the symbolist and art nouveau taste of the period. One is in green-glazed stoneware, which emphasises the vegetation that was modelled around the base, extending up to the woman’s waist and around the man’s genitals, as if threatening to unbalance the swaying couple. Just over 40cm high, it is beautiful, and perhaps what Hugues Fadin, the mayor of Nogent-sur-Seine, had in mind when he opened the museum in March with the statement, ‘We love art, we love sculpture, we love Camille Claudel.’

La Valse (The Waltz) (1889–before 1895), Camille Claudel (1864–1943). Musée Camille Claudel, Nogent-sur-Seine. Photo: Marco Illuminati; © Musée Camille Claudel

The Musée Dubois-Boucher was founded in 1902 with donations from Paul Dubois (1829–1905) and Alfred Boucher (1850–1934), two accomplished sculptors who lived and worked in Nogent-sur-Seine. In 2013, the municipality decided to relocate and rename the museum in honour of Claudel, and to focus the new display around 43 pieces by the artist, many of which were acquired in 2008 from Reine-Marie Paris, the artist’s great-niece and biographer. This is the largest public collection of works by Claudel; it is shown here alongside more than 150 works by other 19th-century sculptors, a combination of the municipal museum’s existing holdings, and pieces on long-term loan from 15 other French institutions. The Claudel family lived in Nogent-sur-Seine, a small town south-east of Paris, for only three years during Camille’s adolescence. In a sense, the Musée Camille Claudel is unlike other museums set in ‘birthplace’ towns, where the landscape, people and economy relate to an artist’s early work: the Musée Matisse in the weaving town of Le Cateau-Cambrésis, for example, or the Musée Courbet in Ornans, in the farming and riverfishing Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region.

The Musée Camille Claudel is designed by Adelfo Scaranello, who has inserted simple, light-filled rooms into the brick shell of the former home of the Claudel family, and designed an extension. The upper floor boasts a panoramic view of the attractive small town, its wealth derived from processing cereals and making sophisticated fire-fighting equipment as well as from the nuclear power plant, the towers of which are visible in the distance. The original collection contains enormous plasters, some rather bland, that have subjects related to historical, allegorical and classical themes – such as Gabriel Jules Thomas’s Man Fighting a Serpent (1893) and Paul Dubois’s Equestrian Statue of Joan of Arc (1889). Claudel’s more intense work is well-placed in five modest-scaled galleries, in which the emphasis is on the evolution of her skills and voice, and on her variations of a single model in terracotta, bronze, marble, and onyx. These displays of her work are wisely not encumbered by too much biographical information, since this would defeat the purpose of understanding the artist’s legacy in its own terms.

Musée Camille Claudel, Nogent-sur-Seine, designed by Adelfo Scaranello

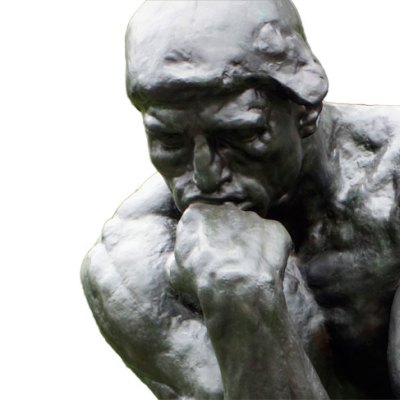

Appropriately, the opening of the museum coincides with the centenary of the death of her teacher and lover, Auguste Rodin (1840–1917). This is currently being commemorated in an ambitious exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris (until 31 July). Conceived by Rodin specialists Catherine Chevillot and Antoinette Le Normand-Romain, the exhibition includes some 330 works and has a particular focus on Rodin as a fearless experimenter, especially in plaster. Shown alongside pieces by younger artists, including Bourdelle and Claudel, and those working today, Rodin’s sculpture nearly always seems more daring and timeless, a view to a degree countered by the exciting focus on Claudel at the new museum.

*

Born in 1864, Claudel began modelling as a young girl and, at her father’s request, she was given occasional tutorials by Boucher. When she moved to Paris, along with her mother and siblings, Claudel attended art classes at the Académie Colarossi. Boucher continued to visit her until he went to Rome in 1882, at which point he asked Rodin to take his place. Claudel joined a group of young women artists renting a studio at 117 rue Notre-Damedes-Champs; it soon became clear that she was Rodin’s favourite student. After a visit to the Salon in early 1883, the painter Léon Lhermitte wrote to Rodin: ‘It was with great pleasure that I saw Mlle Claudel’s figure of a man. It reflects the greatest credit on your teaching.’ With time, being referred to as the master’s protegé struck Claudel as condescending and unjust.

From the outset, Claudel absorbed the method Rodin advocated, to ‘model solely by profiles’ and to pay close attention to the individual model as they moved freely. Adèle Abbruzzesi, one of Rodin’s favourite models, posed in a squatting position, head turned, hand on breast, for his radical work Crouching Woman (c. 1881–82) – which is displayed in the museum next to Claudel’s work of the same name from around 1884–85. Octave Mirbeau referred to Rodin’s cast as ‘the frog’; Claudel’s work, however, is more realistic and believable. The young figure is fuller, and the breasts drop with gravity as she shields her bowed head with her arm. It is just as much a sculptural breakthrough as Rodin’s Crouching Woman.

L’Abandon (The Abandonment) (c. 1886–1905), Camille Claudel. Musée Camille Claudel, Nogent-sur-Seine. Photo: Marco Illuminati; © Musée Camille Claudel

Claudel briefly became one of Rodin’s assistants, working in his studio on the rue de l’Université in the mid 1880s with other gifted artists, including Jules Desbois, and learning about techniques and how to use a single figure in multiple works. The Burghers of Calais, Rodin’s next big commission after The Gates, was realised progressively; studies of the six protagonists include several that are remarkably like Claudel’s small, open-mouthed Head of a Slave (c. 1887), made of unfired clay. Others may indeed be by her or another assistant.

Claudel’s relationship with Rodin developed quickly and they embarked on an intense affair that lasted for more than 10 years. The complex story of how the pair overlapped in this period – both personally and professionally – and the years after, is sympathetically told in Claudel & Rodin: Fateful Encounter, the well-researched catalogue to the touring exhibition organised by the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec and the Musée Rodin in 2005–06. As sculptors, their lives were conditioned by the need to show new work in the annual Salon, to finance an expensive vocation by attracting potential buyers and good critical notices, and to endure the frustrations of protracted negotiations and cancelled or rejected commissions with fortitude and self-belief. From the research presented in this, and other publications, we can be certain that Rodin was beside himself with love. Camille was wilful, possessive and jealous, demanding that he sign a bizarre contract in October 1886; the conditions included a promise to renounce other women, including favourite models and prospective students, to bring her along on his travels, and to marry her in 1887. In return she agreed to receive him in her studio four times a month.

A photograph taken in April 1887 by the fiancé of a fellow pupil shows Claudel working on the large standing sculpture, Sakountala, and it suggests something of her competitive spirit. The two-person group loosely describes the final scene in the story by a Sanskrit poet, in which Prince Douchanta decides not to marry the maiden Sakountala, and his ensuing regret and return. The male figure kneels to embrace the female and ask forgiveness; Claudel’s first title was L’Abandon (The Abandonment). The contact between the couple seems sweaty and tense, and more human compared to Rodin’s lyrical couples in Eternal Idol and Fugit Amor, dating to the same period.

L’Âge mur (The Age of Maturity) (1890–1907), Camille Claudel. Musée Camille Claudel, Nogent-sur-Seine. Poto: Marco Illuminati; © Musée Camille Claudel

One interpretation of Claudel’s masterpiece L’Âge mûr (The Age of Maturity), begun in 1893, is that it represents a male figure being drawn away by a personification of old age, while simultaneously being held back by a figure of youth. But, when linked to a group of angry drawings by Camille, one of which caricatures Rose Beuret, Rodin’s long-term companion, as a witch with a broom, and another showing her glued by her backside to Rodin, the three-figure sculpture, so disturbing and unforgettable, clearly seems autobiographical. Beuret is wrapped in Rodin’s embrace, and Claudel is on her knees, begging him to choose her. The bronze version includes a sweeping backdrop that goes from undergrowth to canopy, fashioned with deep recesses; it was described by the artist’s brother, Paul Claudel, as related to ‘the Wagnerian melopoeia’ – an example of how he projected his own poetic sensibility on to her work while overlooking its message of desperation. The young female figure is known as The Implorer; Claudel’s variation of the older woman, Clotho (1893), loops skeins of stringy hair around her emaciated body in an image that invites parallels with Donatello’s wooden Mary Magdalene (c. 1455).

In the late 1890s, perhaps deliberately attempting to move beyond Rodin, Claudel changed artistic direction in her experiments with groups of small-scale figures placed within sculptural environments, which were inspired by watching people on the street or in a train carriage. The Gossips (1893–1905) depicts an animated huddle of four nude yet perfectly coiffured women, while the introspective Deep Thought (c. 1898), sees an ordinary woman wearing a long dress kneel before a fireplace, her arms raised to the mantelpiece. Combining bronze and marble, one version features logs in the hearth, the other leaves the setting empty. Addressing mental frailty from a female perspective, as so many of her works do, marks Claudel’s art as unusually courageous. This candour, and the quality of her art, have rightly earned her dedicated fans, just as Frida Kahlo’s paintings have by communicating her physical pain and similar loneliness.

Persée et la Gorgone (c. 1897–1902), Camille Claudel. Musée Camille Claudel, Nogent-sur-Seine. Photos Marco Illuminati; © Musée Camille Claudel

Claudel’s creativity came to an end when she was 41, following years of growing paranoia. Perseus and the Gorgon (1902), commissioned by Countess Arthur de Maigret and carved by François Pompon, is a large marble endowed by Claudel with frightening neoclassical overtones; one assumes that the raised trophy head of Medusa is a self-portrait. By this point in her career, Claudel was convinced that she was being persecuted, especially by Rodin; in her letters she complains of his ‘malevolent hand working behind the scenes to divest me of all my friendships’. Rodin, like her parents and supporters – among them Mathias Morhardt and Eugène Blot – sent Claudel regular stipends to help ward off impoverishment and continually tried to arrange sales and opportunities for her to show her work. He wanted a room devoted to Claudel’s work in the future Musée Rodin, and one eventually opened in 1952.

The last portrait Claudel made was of her younger brother Paul, a writer and diplomat. Paul Claudel à 37 ans (1905) captures his unwavering look; by this point he was a public figure who disapproved of his sister’s affair. After the family committed an admittedly ravaged Camille to a mental asylum in 1913, her persecution-complex continued. She kept writing letters, hoping her family might forgive her for ‘shaming’ them and come to her rescue.

During the 1890s, the ‘Balzac’ years, Rodin passed through his own periods of depression and anxiety, fed by a sense of being misunderstood. He seemed to allude to how much he missed Claudel by adapting his portraits of her in works for this time: in an assemblage in the Musée Rodin, Pierre de Wissant’s left hand, modelled in plaster, cradles a head of Claudel that Rodin made shortly after he had met her, the drops of plaster and mould lines adding to a sense of vulnerability. In studies for a rejected monument of Victor Hugo, Rodin gave the national hero a flabby physique, but it is clear that the writer was drawing inspiration from the two muses by his side. One was Meditation, also called The Inner Voice (1896). She originated as a figure for the tympanum of The Gates but enlarged, now carried something of Claudel’s physique: her own Wounded Niobid (1906) echoes Rodin’s inward-looking figure.

The Musée Camille Claudel allows us to reconsider the achievements of an artist whose artistic identity has long been assessed alongside that of Rodin. The curator Cécile Bertran now has the opportunity to link Claudel’s legacy to sculptors other than Rodin. It should extend public appreciation of a tenacious, original artist whose excess of feeling was one of her strengths.

To find out more about the Musée Camille Claudel, visit the museum website.

From the May 2017 issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.