In January 2016 Norman Kleeblatt, the Susan and Elihu Rose Chief Curator at the Jewish Museum, New York, shared his plan for a small exhibition of Sargent’s brilliant portrait of my great-grandmother and her children. The Warburg Mansion dining room on Fifth Avenue provides the perfect setting for this masterpiece. The portrait of Adèle Meyer and her two children, Elsie aged 11 and Frank aged 10, caused a sensation at London’s 1897 Royal Academy Summer Exhibition. Subsequently lent to Sargent’s one-man show in Boston in 1899 and the Paris International Exhibition in 1900, this masterpiece was bequeathed by Adèle in 1930 to the National Gallery, Millbank with a lifetime’s interest for my grandfather Frank and my father Anthony. The painting left family ownership for Tate Britain after my father’s death in 2004.

Mrs. Carl Meyer and her Children (1896), John Singer Sargent. Courtesy of Tate Britain

As a child I was fascinated by the portrait which hung on the staircase adjacent to my bedroom in my parents’ home in Berkshire. Adèle’s sumptuous pink satin dress was even more elegant than the occasional ball gown worn by my mother, and I was intrigued by her confident manner – there was a strong personality to encounter whenever I emerged from my room. I identified particularly with Elsie, the beautifully poised daughter behind the settee.

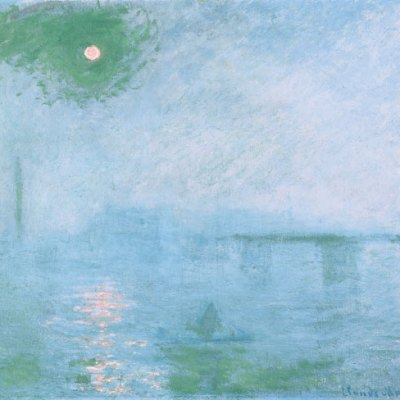

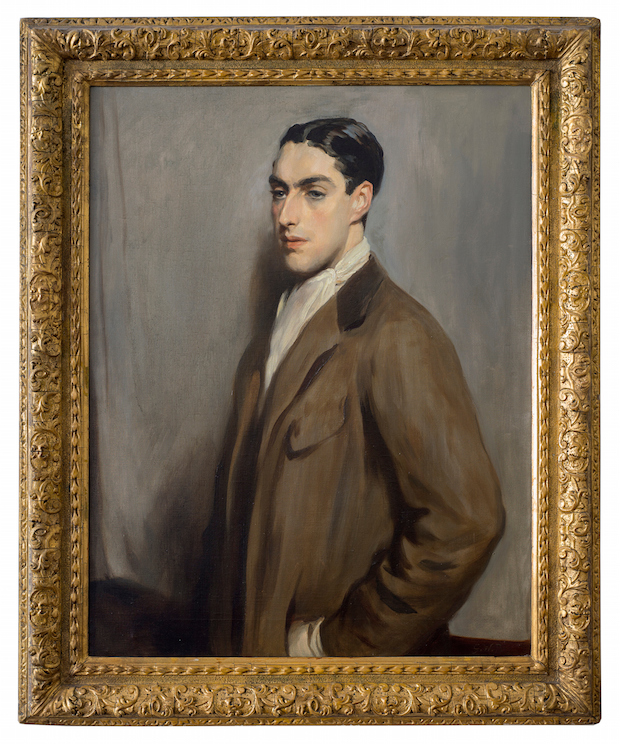

In New York, the Meyer Sargent, glistening after recent cleaning, is shown with Hubert von Herkomer’s 1908 portrait of Carl Meyer painted in the dining room of their country home, Shortgrove, Essex, with the Sargent in the background. An elegant 1911 portrait of Frank in riding clothes by Glyn Philpot anticipates Philpot’s 1917 portrait of Siegfried Sassoon. A charcoal of Elsie, commissioned from Sargent as a surprise for her parents’ 25th wedding anniversary in 1908, was sketched the year before her own marriage.

Frank Meyer (1911), Glyn Philpot, Private Collection. Image courtesy of the Jewish Museum, New York

Four albums of autographs, photographs and sketches compiled by Elsie from 1902–07 illustrate family life. On New Year’s Eve in 1902 the Meyers performed a fairytale extravaganza, ‘Our Toys’, with Adèle as Little Bo Peep, and Elsie as Little Red Riding Hood. At Shortgrove from 1903 onwards, they hosted house parties for Newmarket races where Carl would rub shoulders with other leading financiers. These included the Rothschilds, his former employers for 25 years, and Ernest ‘Windsor’ Cassel, an old family friend and close colleague at the National Bank of Egypt; Cassel from Cologne and Meyer from Hamburg. Carl’s racing purse and gold vesta with Rothschild racing colours can now be seen at Newmarket’s Palace House, the National Horseracing Museum. Carl’s gift of £70,000 towards the foundation of the National Theatre earnt him a baronetcy in 1910 – a caricature by Max Beerbohm captures Carl’s quiet demeanour yet serious resolve.

Mr. Carl Meyer (c. 1910), Max Beerbohm, Private Collection. Image courtesy of the Jewish Museum, New York

But Adèle’s glamour belies her important role as a philanthropist. With Clementina Black, Adèle researched the working lives of women in the textile trade, publishing ‘The Makers of our Clothes’ in 1909. Adèle campaigned vigorously for women’s suffrage and hosted politically-motivated actresses for a Suffragette weekend just after Elsie’s wedding.

Photograph of Adèle Meyer, Private collection. Image provided by Cultural Heritage Digitisation Ltd

The current display is a sequel to the Jewish Museum’s exhibition ‘John Singer Sargent: Portraits of the Wertheimer Family’ (1999/2000), also curated by Norman Kleeblatt. The Meyers knew the Wertheimers, for Alfred de Rothschild was an important client and Carl served as Alfred’s private secretary from 1872–97. Elsie Meyer and Miss Wertheimer sold programmes at the gala performance in aid of the Westminster Children’s Hospital (now part of Chelsea and Westminster). This was endowed in memory of Adèle’s younger sister Edith, wife of Robert Mond, who died in tragic circumstances on the Nile in 1905; this was the inspiration for Agatha Christie’s 1937 novel Death on the Nile.

‘John Singer Sargent’s Mrs Carl Meyer and Her Children’ is at the Jewish Museum, New York, until 5 February 2017.