The names chosen for arts organisations rarely state their aims as clearly as Artes Mundi (Latin for ‘arts of the world’). The Cardiff-based initiative most well known for its biennial contemporary art prize and accompanying exhibition proudly broadcasts its international scope. Artists from anywhere in the world can be nominated for the £40,000 prize – in contrast to the Turner Prize, which requires its nominees to be either born or working in Britain. No such provincialism here: although the exhibition is firmly rooted in Wales (now in its seventh edition, it has for the past 12 years taken place at the National Museum Cardiff and other nearby arts centres), selected artists not only represent a broad range of national identities, but are also united by their works’ concern with what Artes Mundi’s director Karen MacKinnon describes as ‘global issues’.

Installation view of World Domination (2012) by Neil Beloufa at ‘Artes Mundi 7’, Cardiff. Photo: Polly Thomas

This year’s goal is to bring together artists who explore social issues relating to the ‘human condition’. We pass through war-torn Lebanon (in Lamia Joreige’s impressive project Under-Writing Beirut) and post-Soviet Ukraine (in Neïl Beloufa’s Monopoly, a darkly comic examination of the performativity of capitalism), and are taken on a sea voyage by Amy Franceschini’s collective Futurefarmers. It is a relatively rare treat within a globalised art world (note the singular) dominated by the English language, that in these works the sounds or signs of other languages proliferate. Elsewhere, in films and installations by John Akomfrah, Nástio Mosquito and Bedwyr Williams, ambiguous or invented landscapes are presented to explore questions of migration, power and urbanisation – global issues aplenty.

Installation view of Auto Da Fé by John Akomfrah at ‘Artes Mundi 7’, Cardiff. Photo: Polly Thomas

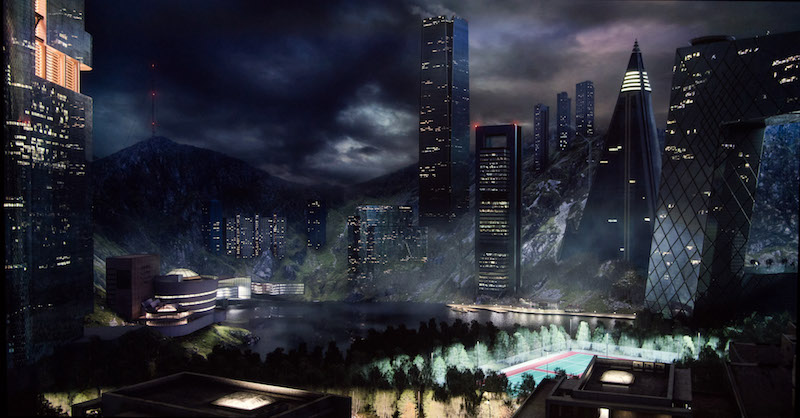

That the works displayed here often confront difficult or topical issues suggests a certain seriousness. But the inventive ambition, style and, in several cases, black humour of the works serve to counter this. Nowhere is this better demonstrated than in Welsh artist Bedwyr Williams’s contribution, Tyrrau Mawr (2016), a computer-generated image depicting a fictional city set amidst the picturesque mountains of Snowdonia in North Wales. Projected onto a colossal screen in a dimmed, cavernous gallery, it makes a striking initial impression. It also rewards prolonged attention, not just to the intensely detailed image, but also to the layered narrative of the lives of the city’s residents past and present, which emerges through a voiceover spoken by the artist.

When I speak to Williams about the prize he admits that when he was first nominated, although very flattered, he had some reservations. The theme, the human condition, he tells me, ‘can be about anything, can’t it?’ Williams has risen to prominence less for any social or environmental activism than for the persistent, engrossing strangeness of his work. He fuses performance and poetry with video, sculpture and installation, taking in diverse subject matter often drawn from his own personal experience. There’s his 2012 performance presented at Frieze London, in which Williams dissected a life-sized curator made of cake, and currently on show at the Barbican is ‘The Gulch’, an immersive journey featuring talking goats, singing running trainers and psychedelic hypnotherapy. Surreal, playful, even absurd, the Barbican exhibition seems a far cry from Williams’s Artes Mundi contribution, which enacts a dystopian critique of rapid, spreading urbanisation. And yet, there is certainly an element of absurdity to the idea, realised in Tyrrau Mawr, of placing a futuristic mega-city right in the middle of a National Park.

Tyrrau Mawr by Bedwyr Williams at ‘Artes Mundi 7’, Cardiff. Photo: Polly Thomas

Williams tells me that he was inspired by a conversation with an architecture writer who had been to visit a city under construction in the Middle East. The city didn’t exist yet, but in 12 months it would be fully inhabited. The artist began to think of Wales, a country never transformed by any major settlements, as an interesting anomaly. On a hiking trip in the mountains with his brother, Williams began to photograph the landscape, planning his own imagined architectural project.

It seems to me that in the geographical context of Artes Mundi, the creation of a piece that centres on his native country – where Williams currently lives and works – is a bold statement. Williams insists, however, that ‘it’s not some big Welsh thing or anything’. Tyrrau Mawr does, however, reference the National Museum’s extensive collection of historic Welsh landscape paintings; Williams used a technique called ‘matte painting’ commonly employed by filmmakers to make illusory backdrops in super high resolution. Created with 3D modelling, photography and compositing, the image ‘works on some level like a painting, because you can stare at it in a way that you can’t stare at a projection usually.’

I suggest, nonetheless, that there’s a connection between the work’s implicit commentary on the destruction of local communities caused by global urbanisation, and the globalised art world in which we exist – and which Artes Mundi is part of. Williams agrees, but for him the main issue is the homogeneity of the rootless mega-cities which he encounters on his travels to international fairs and exhibitions. They all ‘look the same’, and seem to symptomise ‘that kind of mercantile, cash-based world that we live in; it’s horrible…frightening…depressing.’

Nastio Mosquito with his work The Transitory Suppository at ‘Artes Mundi 7’, Cardiff. Photo: Polly Thomas

Williams contends, however, that beneath the relatively ‘conservative’ appearance of his new work, there’s plenty of covert silliness. He recounts one of the stories in the piece (inspired, apparently, by real events) about a group of teenage boys at a sleepover who, after too many energy drinks, begin to beat each other up. It certainly provokes laughter, but the latent violence inherent in this tale seems to me particularly horrific. It reminds me of the ‘laugh or you’ll cry’ audacity of Neïl Beloufa’s 2012 piece World Domination, also in the exhibition, where non-professional actors are shown suggesting a series of increasingly violent solutions to various geopolitical crises. In both of these works, wandering between fiction and reality, the precarious distinction between comedy and tragedy collapses, revealing a willingness to capture the darker side of the human condition. As Williams puts it, summarising the many layers with which he has built his monumental city: ‘All human life is here.’

‘Artes Mundi 7’ is on show at the National Museum Cardiff and Chapter, Cardiff until 26 February 2017, with the prize announced in January 2017; ‘Bedwyr Williams: The Gulch’ is at the Barbican, London, until 8 January 2017.