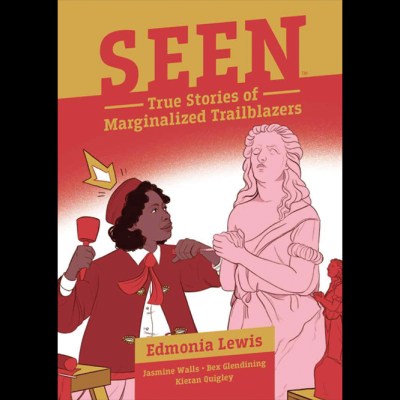

Museum comics have become a subgenre unto themselves. August institutions such as the Louvre and the Prado now have their own lines of comics, while everywhere from the British Museum to the Anne Frank House has commissioned didactic or promotional comics, marketed (of course) as ‘graphic novels’. At the same time, cartoonists are increasingly turning their attention to artists’ biographies – Van Gogh alone has been given the comics treatment at least half a dozen times over the last decade.

Cartooning is a labour-intensive, financially precarious profession for most, so it is easy to see why cartoonists pursue this kind of work, which even when not generously funded by a commissioning institution or grant-giving body is eminently marketable to bookstores, libraries and schools. For museums the phenomenon is surely part of the eternal pursuit of younger audiences.

The problem is that the results are rarely more than mediocre, even when top-flight talent is employed: artists such as Nicolas de Crécy, Naoki Urasawa, David Prudhomme and Taiyo Matsumoto – all prominent in the world of comics – have phoned in product for the Louvre, while the Prado failed to coax more than a pretty but minor effort from the great Spanish comics artist Max. And for every Gina Siciliano – whose comic about Artemisia Gentileschi, I Know What I Am (2020), shows genuine artistic investment – scores of lacklustre ‘educational’ snoozers crowd the museum bookshelves.

Thankfully, The Grande Odalisque is not a museum comic, even if – as a rare comics entry into the art-heist subgenre so popular in prose fiction and on screen – it is concerned with the glamour of Old Masters. It is hard to imagine a work so irreverent in its handling of cultural heritage being commissioned by a museum. Originally published in 2012 and now available in English, it is, rather, an attempt at widescreen entertainment from three creators who originally established their credentials with more experimental comics: the cartoonist team Florent Ruppert and Jérôme Mulot joining up with comics wunderkind Bastien Vivès.

Courtesy Fantagraphics Books

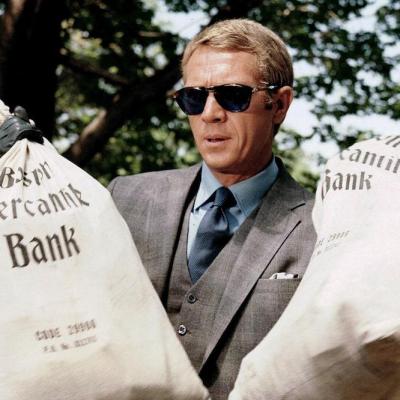

The story features a trio of young, beautiful and frankly rather bland women – Carole, Alex and Sam – who steal art by means of dizzying acrobatics, fast cars, hang-gliders, motorcycle stunt rides and rifles firing elephant tranquillisers. In the opening sequence they cut Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe from its frame at the Musée d’Orsay, but the set-piece heist is at the Louvre and concerns Ingres’ Grande odalisque, ‘That painting of the chick with the three extra vertebrae. The whole disregarding-realism-to-accentuate-beauty thing.’

That line is basically the comic’s aesthetic manifesto. We spin backwards from the overt disenchantment of the grand manner in Manet to Ingres’ ironic vision of classic beauty. When, during the heist, Carole hides behind Laurent de La Hyre’s Laban Searching Jacob’s Baggage for the Stolen Idols – an immaculate example of French 17th-century classicism – to escape from a SWAT team, it ends up riddled with bullets: ‘Paintings can be restored,’ says the colonel, overruling his art-loving colleague who protests, ‘But… it’s a Titian.’ It clearly is not, which seems to be the point: Titian predates the cultural orthodoxy of academic classicism that Ingres and Manet subverted in efforts that themselves have become commodified and orthodox.

Courtesy Fantagraphics Books

I am giving the cartoonists the benefit of the doubt here, assuming they are not merely misidentifying the La Hyre – something I would have thought them too smart to do. Their plan seems to be to expose the superficiality of cultural elitism by means of a shallow action comic of decidedly sexist bent. The governing trope is that of sassy girls sticking it to the establishment, with the primary source apparently being the 1980s Japanese anime series Cat’s Eyes, which featured three sisters stealing art. Our trio of male creators, however, infuse this conceit with a girl-on-girl frisson that serves the male gaze more readily than it does any notion of liberation.

Depersonalised cynicism has been a key component of Ruppert and Mulot’s often formally daring explorations of human amorality and patterns of behaviour, along with a propensity for kinetic action that borders on abstraction. They have often extended their work beyond the comics page into performance and installation art. Particularly relevant in this context, perhaps, is the sprawling comics jam on a bordello theme that they staged as a peep show at the Angoulême comics festival in 2009, much to the consternation of various second-wave feminist critics. Vivès, for his part, has excelled from the beginning at that particularly French pastime of conflating sensuality and mystery in the highly aestheticised depiction of young women.

The Grande Odalisque reminds us that comics, by virtue of their sequential visuals, are eminently well-suited to the procedural story-telling central to the heist genre and, furthermore, that the form offers an effective way of mobilising so-called fine art for new aesthetic and story purposes. The cartoon idiom allows the artist greater leeway for interpretation without alienation than does the verisimilitude of photography: when redrawn in a given cartoonist’s personal style, even famous artworks can attain a new life that is much harder to arrive at with the kind of low-quality photographic reproductions or feeble recreations that often stand in for known masterpieces on film.

The problem here is that the authors’ provocative foregrounding of reactionary tropes and embrace of superficiality ends up coming across as, well, sexist and shallow. The action sequences at times attain balletic elegance and thankfully take us beyond the staid institutional vibe of many museum comics, but ultimately the reader is left without much to show for it.

The Grande Odalisque by Bastien Vivès, Florent Ruppert and Jérôme Mulot (translated by Montana Kane) is published by Fantagraphics.