From the July/August 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Although it is located just a dozen miles from downtown Los Angeles in San Marino, the Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens feels like it is worlds away. Essentially a European-style Gilded Age cultural institution transplanted to Southern California, it boasts a research library featuring 11 million items from the last millennium, one of the finest collections of 18th-century British Grand-Manner portraiture outside the UK and 130 acres of lush, sprawling landscape filled with flora from around the world. But, as removed as it may seem from the contemporary realities of life beyond its gates, over the past few years the Huntington has been considering new ways to address diverse audiences, contested legacies and complex times.

Natalia Molina, a historian on the Huntington’s board of governors, tells me: ‘It’s exciting to see how the Huntington, like so many cultural institutions, is increasingly becoming not just more public-facing but engaging many publics, which includes a reckoning with its past.’ Appropriately, Molina is writing a book called The Silent Hands that Shaped the Huntington: A History of Its Mexican Workers.

Founded in 1919 by Henry Huntington and his wife Arabella, the Huntington is of a piece with other institutions established by Gilded Age robber barons and kings of industry, such as Henry Clay Frick, J.P. Morgan and Andrew Carnegie. Huntington was a railroad and real-estate magnate who built a sprawling network of streetcars connecting several neighbourhoods in central Los Angeles. He was also staunchly anti-union, going so far as to call labour organisers ‘un-American aliens’ and hiring only non-union workers to construct his library, as Carolina A. Miranda wrote in the Los Angeles Times last year. Miranda also notes that he paid his Mexican workers, who often lived outside San Marino, less than his white workers.

Henry Huntington (1850–1927) photographed by Theodore C. Marceau in 1907. Photo: courtesy the Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens

The Huntingtons amassed an impressive collection of art and rare books, including Grand Manner paintings such as, notably, Thomas Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy (c. 1770) – and 18th-century decorative arts from France, as well as priceless books such as a vellum copy of the Gutenberg Bible, one of 12 in existence. Henry purchased the land on which the Huntington now sits in 1903 and chose architects Myron Hunt and Elmer Grey to design a Beaux-Arts mansion for his residence. In 1919, Huntington and his wife Arabella agreed to turn their private estate over to the public and, in 1928, a year after Henry’s death, the Huntington opened its doors.

The museum now boasts more than 42,000 objects spanning 500 years of European and American art, split between the Huntington Art Gallery (the repurposed Huntingtons’ home), and the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art, opened in 1984. These include William Blake’s watercolours for Milton’s Paradise Lost, landscapes by Constable and Turner and works by 20th-century American artists such as Andy Warhol and Charles White. The Botanical Gardens feature more than a dozen themed gardens, from a recently redesigned Chinese garden with a lake, waterfalls, and a tea-house, to a desert garden with one of the world’s largest collections of cacti and succulents and a rose garden with more than 1,000 different cultivars. Wandering through dense jungle canopies and bamboo thickets, it can be easy to forget you’re just outside the city of Los Angeles, which is currently experiencing one of Southern California’s worst droughts in decades. About 2,000 researchers a year are given access to the Library, which covers British and American histories, maps, manuscripts, Hispanic history and culture and various archives, including those of pioneering African-American science-fiction author Octavia Butler, who lived in nearby Pasadena, and Eve Babitz, chronicler of LA’s high times.

The Large Drawing Room, one of the first-floor period rooms in the Huntington Art Gallery building that were inhabited by Henry and Arabella Huntington. Photo: Tim Street-Porter; courtesy the Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens

Over the past decade, museums have been reappraising their role and function, from how they present their collections to the public to how they operate behind the scenes. The Huntington, with its Eurocentric focus and its Gilded Age framework, had a lot of reappraising to do, especially since it exists in one of the most diverse regions of the United States. ‘I wanted to look at [our collections] and think about the broader social and historical context in which they were produced,’ says Christina Nielsen, director of the art museum. ‘We’re thinking about what voices are quiet in our collections and galleries.’

Shortly after Nielsen became director in 2018, she and Karen Lawrence, the Huntington’s president, discussed their admiration for ‘Made in LA’, the Hammer Museum’s biennial exhibition of Los Angeles artists. Nielsen pitched an unlikely collaboration. ‘Who would have thought that the Huntington and the Hammer would work together? [Hammer director] Annie Philbin saw the draw immediately,’ Nielsen says. ‘What amazed me was the degree to which artists were interested in engaging with Huntington.’ The 2020 edition of ‘Made in LA’ (postponed to 2021 due to Covid), was split between the Hammer and the Huntington, with all 30 artists represented at each venue. Whereas the Hammer was more akin to a white cube, the Huntington intermingled contemporary works with its collection in a smart, creative dialogue. In his dramatic triptych The Battle of Malibu (In Three Parts) 1795 (2020), Umar Rashid imagined an alternate history where indigenous peoples bested their colonial adversaries. His paintings were hung between windows looking through to the permanent collection, heightening the disconnect between the narratives proposed in each space. Monica Majoli’s delicate woodblock prints depict images from the ’70s gay magazine Blueboy, a sly riff on the Gainsborough portrait. Buck Ellison actually placed his photograph of status symbols Untitled (Cufflinks) (2020) in one of the permanent galleries, in direct conversation with an earlier depiction of the upper crust, John Singleton Copley’s portrait The Western Brothers (1783). ‘It shook things up in very productive ways,’ says Dennis Carr, chief curator of American art at the Huntington. ‘It occupied galleries in the American space that we had to reimagine.’

‘Made in LA’ was not the Huntington’s first project with contemporary artists, though perhaps it is the most ambitious so far. In 2016, it mounted ‘/five’, a series of five year-long collaborations with organisations such as the Feminist Center for Creative Work and the Vincent Price Art Museum. In 2019, it launched a series of three exhibitions curated by Hilton Als that originated at the Yale Center for British Art. The third and final exhibition of work by Nigerian-born, LA-based artist Njideka Akunyili Crosby will open early next year. New installations by Mineo Mizuno incorporate found wood and ceramic dogwood blossoms, integrating the natural world into the composed, mannered setting of the Huntington Art Gallery.

Installation view of Kehinde Wiley’s A Portrait of a Young Gentleman (2021) in the Thornton Portrait Gallery. Photo: Joshua White; courtesy the Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens

Then, last autumn, the Huntington commissioned prominent African American artist Kehinde Wiley to paint a work inspired by Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy. Titled A Portrait of a Young Gentleman (The Blue Boy’s original title), Wiley’s portrait depicts a young Black man gazing at the viewer with the same immediacy as Gainsborough’s dandy. They strike similar poses, though Wiley’s subject wears his hair in blond dreadlocks and sports trainers and an Apple watch instead of a blue suit and lacy cravat. The two portraits hung across from one another in the Thornton Portrait Gallery until earlier this year when the Gainsborough returned to England for an exhibition, the first time it had travelled since Huntington received it in 1922. For several months, Wiley’s was the only Gentleman at the Huntington.

Also last autumn, the Huntington announced a partnership with the Ahmanson Foundation ‘designed to build on the Art Museum’s strengths; diversify the collection by adding masterworks by women and artists of color; and underscore the connections among the Huntington’s art museum, library and botanical gardens,’ according to a press release. The announcement came a year and a half after the foundation abruptly terminated its partnership with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, to which it had donated more than $130 million in art over 60 years, making it LACMA’s biggest donor of European Old Masters. The split was the result of LACMA’s bold new direction, spearheaded by its director Michael Govan, which includes an ambitious and controversial new building designed by Swiss architect Peter Zumthor, as well as a reimagining of the permanent collection galleries towards thematic shows that cut across aesthetic traditions, disciplines, eras and cultures. In short, the Ahmanson family feared that its donations would be hidden from view, locked away in storage.

Despite the Huntington’s avowed desire to collect ‘masterworks by women and artists of color’, the first acquisition made possible by the Ahmanson partnership was Portage Falls on the Genesee (c. 1839) by Anglo-American painter Thomas Cole. It is the Huntington’s first painting by Cole – largely regarded as the founder of the Hudson River School – and depicts a landscape that would be drastically altered by human intervention. Nielsen connects the painting to current discussion around the climate crisis. ‘They were hugely concerned with man’s impact on the natural landscape,’ she says of the Hudson River School. It remains to be seen if future acquisitions made possible by the Ahmanson gift will align more closely with the Huntington’s stated progressive goals.

Portage Falls on the Genesee (c. 1839), Thomas Cole, The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino

In addition to rethinking what they exhibit and how it’s presented, the Huntington released a formal strategic plan for diversity and inclusion in 2020, and has hosted programmes such as last year’s ‘White Supremacy in the West: Immigration and Racial Justice in Southern California’, featuring a conversation between Natalia Molina and author Kathleen Belew, an authority on white supremacy. Still, its administration and curatorial staff are overwhelmingly white. ‘Of the 250 knowledge workers (curators, librarians, administrators), only 17% are BIPOC [Black, Indigenous and people of colour]. And while there are BIPOC curators in the gardens and the library, the art museum counts not a single BIPOC curator among its staff,’ Carolina Miranda reported in the Los Angeles Times a year ago. Since then, the museum has hired curators from a range of backgrounds: Yinshi Lerman-Tan as an associate curator of American art and Linde B. Lehtinen as curator of photography.

These developments paint a picture of an institution grappling with its past, while trying to forge a new direction forward. In 2019, it changed the words ‘Art Collections’ to ‘Art Museum’ in its name, signalling a more open and less exclusive tone. The Huntington’s collections are of course still the cornerstone, but ‘museum’ suggests the possibility of growth beyond a static grouping of objects. ‘The idea of “collections” seems rather private sometimes, and “museum” is clearly legible to the public that you’re invited to come,’ Lawrence told the Los Angeles Times.

If ‘Made in LA’ and Kehinde Wiley’s Portrait of a Young Gentleman are interventions in the Huntington’s collections, then ‘Borderlands’ is an expansive reinterpretation of the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art. It features works by Mary Cassatt, Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer, alongside contributions from contemporary artists Sandy Rodriguez, Mercedes Dorame, Cara Romero and Enrique Martínez Celaya, who covered the galleries’ windows with paintings of local birds and their migratory patterns, again fusing art and nature. Before entering the galleries, visitors are greeted by this land acknowledgement: ‘The Huntington exists on the ancestral lands of the Gabrielino-Tongva and Kizh Nation peoples who continue to call this region home.’ As Dennis Carr puts it, ‘The Huntington has one of the largest living collections in the world; a research library, and a world class art collection, all in one place. What was missing was an indigenous perspective.’

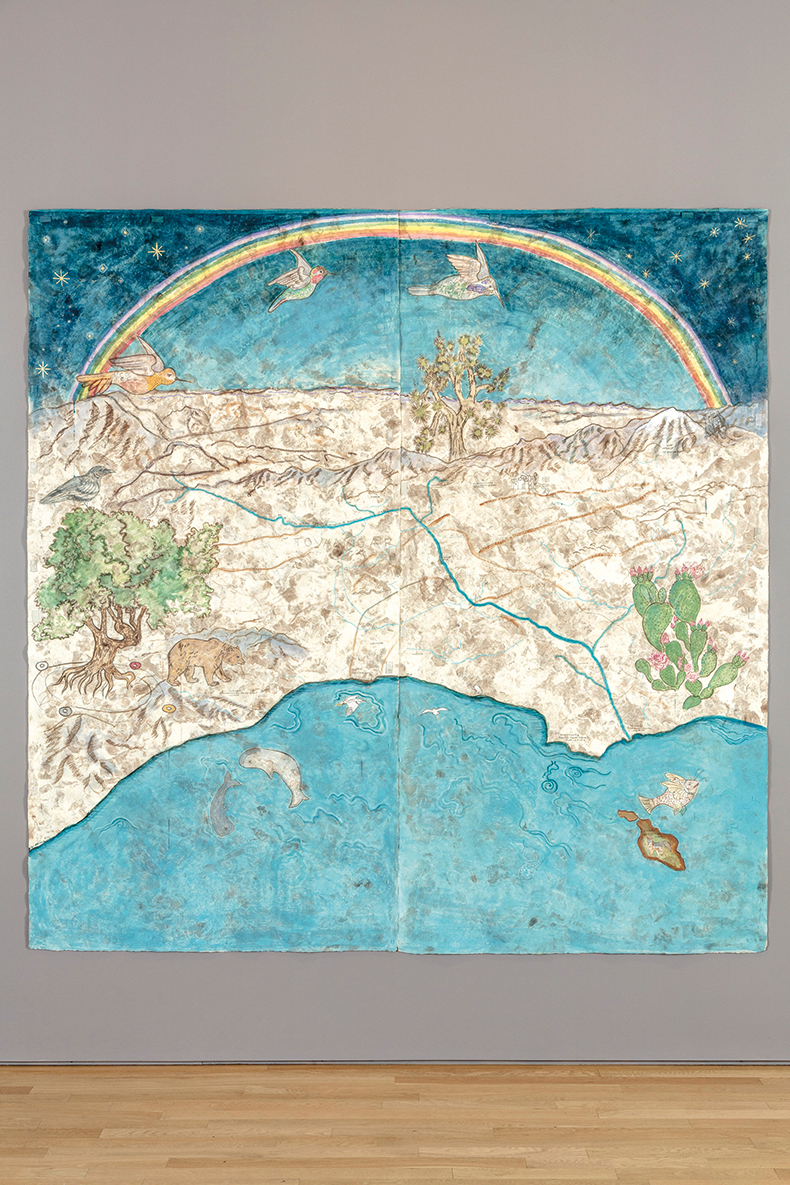

Installation view of YOU ARE HERE / Tovaangar / El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciúncula / Los Angeles (2021) by Sandy Rodriguez, part of the ‘Borderlands’ exhibition. Photo: Joshua White/JWPictures.com; courtesy the Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens

A highlight of the installation is Sandy Rodriguez’s YOU ARE HERE / Tovaangar / El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciúncula / Los Angeles. The multilingual map charts the flora, fauna and various peoples that have called the city home. The artist painted it with locally found pigments on amate paper, a fig-bark paper used in Mexico before being outlawed by the Spanish in the 16th century. ‘My goal is to dispute Western, European and American narratives and challenge audiences to interrogate these legacies of colonial aggression in our daily lives,’ Rodriguez says. ‘It is precisely in these collaborations in “Borderlands” that we have the potential to have discussions with objects that allow for a range of perspectives.’ In addition to her artworks, ‘Borderlands’ features an educational space that recreates Rodriguez’s home studio, where she mixes pigments using indigenous practices.

Chemehuevi artist Cara Romero’s photograph offers a proud depiction of Native Americans, juxtaposed with more essentialist, anthropological portrayals from the collection. ‘They’ve done an excellent job curating with relevant, modern flair what people are hungry for: truthful histories; how Native American, immigrant, and diasporic populations fit into American history to make us who we are,’ she says.

In addition to a photograph of a grinding bowl carved into a boulder – itself a kind of embodied landscape – Mercedes Dorame contributed an alternative didactic wall text for Edgar Alwin Payne’s painting San Gabriel Valley (c. 1916). ‘Looking at these mountains, as a Tongva person who grew up in Los Angeles, I cannot escape the feeling of home. A home of longing, a home that is kept always at a distance, a home that has been dissected, privatized, and monetized, but one that I remain deeply connected to,’ reads part of her text.

The contemporary artists in ‘Borderlands’ provide representation where there was absence, complication instead of clarity – albeit a clarity that was based on exclusion. It presents not so much a break with the past as a difficult recuperation. ‘We can look at a piece made in a different space and time and recontextualise it and see it as problematic – not to erase it, but with the hope that we don’t recreate the same problems,’ Dorame says. ‘We can’t go forward unknowingly.’

From the July/August 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.