In 1905, John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) went to the Holy Land in search of inspiration for The Triumph of Religion, his great mural scheme in the Boston Public Library. He was planning to paint the Sermon on the Mount on the central panel of the east wall of the library hall and the desert landscapes he painted in the environs of Jerusalem and Mount Tabor must have been executed with this subject in mind. Sadly, Sargent died before embarking on the main panel, which remains blank to this day. Sargent liked to have company on his expeditions and tried to persuade a number of artist friends to travel with him, including Albert de Belleroche and Wilfrid de Glehn, who both turned him down. However, four years ago, an important cache of letters sent by Sargent to the Italian painter Alberto Falchetti (1878–1956) between 1905 and 1909 was discovered in a private collection in Piedmont, revealing that Falchetti accepted Sargent’s invitation and throwing fresh light on Sargent’s links with the Italian art of his day.

Sargent, who was born in Florence, was aware of developments in Italian painting from a young age. In 1874, he became a student at the Accademia di Belle Arti, where he seems to have studied anatomy as well as painting. It is clear from the style of his early landscapes that he was responsive to the work of the Macchiaioli, the influential group of Italian proto-Impressionists. After moving from Florence to Paris in the mid 1870s, he exhibited at the Galerie Georges Petit with Giovanni Boldini and Giuseppe De Nittis, and established a friendship with Antonio Mancini, whose career he would help to foster (Sargent once described him as the ‘best living painter’). In the early 1900s, when he was living in London, Sargent formed friendships with a band of northern Italian artists in the western Alps, at Purtud in the Val d’Aosta, on the Italian side of the Mont Blanc massif. These included four artists from Piedmont and Lombardy: Ambrogio Raffele, Carlo Pollonera, Carlo Stratta, and Alberto Falchetti.

Alberto Falchetti, known to everyone as ‘Bertino’, was born in Caluso (not far from Turin) in 1878. Unlike Raffele, Stratta and Pollonera, who studied under Antonio Fontanesi in Turin, Falchetti had no formal art training, apart from lessons given to him by his father Giuseppe Falchetti, a landscape and still-life painter.

After a brief trip to Paris in the mid 1890s, Falchetti returned to Italy and became a follower of Giovanni Segantini, from whom he derived his technique of threadlike Divisionist brushstrokes, characterised by the juxtaposition of stripes of pure colour applied on the canvas without being previously mixed on the palette. This created an intense effect which he applied to Alpine landscapes or to views of the Italian coast. Segantini, whose works depict poetic mountain scenes with cattle and peasants as protagonists, wrote to Falchetti in a letter of 28 May 1899: ‘I would suggest you abandon the city moving to a small village to study and to paint simple pieces of nature driven from your soul,’ adding, ‘That’s the only way to discover and find your own depth.’

Following Segantini’s advice, in the early 1900s, Falchetti retired to isolated villages in the Val d’Aosta, which provided him with inspiration for the large landscape paintings he would later exhibit in Turin and Milan, and where he would paint en plein air. He went to stay first in the Val d’Ayas, in the company of his brother Ernesto and the writer Augusto Sebastiano Ferraris (better known as Arrigo Frustra), and then moved to the foot of the Giomein glacier, in Valtournanche, near the Hôtel du Mont Cervin, where he met Sargent in July 1905.

Falchetti was staying in a mountain refuge, known as il nido dei solitari (the solitary nest), and it was there that Sargent painted the powerful and brooding portrait of the Italian artist that caught the attention of the writer Edmondo De Amicis, who saw it in the Hôtel du Mont Cervin that same summer. Writing about Sargent’s portrait in an article published in an Argentine newspaper called La Prensa, De Amicis commented on Falchetti’s looks, describing his head ‘like that of Giorgione’, as well as his perfect physiognomy, and his ‘thick hair, the big beard, and his two bright eyes’. At the time of the portrait, Falchetti was painting Alpine View, a large canvas that would form part of a triptych he exhibited at the Esposizione Nazionale of Milan in 1906. Also staying in this refuge was Padre Giulio Albera, a reclusive Salesian priest with an interest in botany, whom Sargent portrayed in the act of recording plants. A photograph taken by Arrigo Frusta and preserved in the Centro Studi Piemontesi of Turin (Fondo Frusta) shows Falchetti standing on the right-hand side of the group, wearing the same hat he is wearing in Sargent’s portrait, with Padre Albera sitting at his feet. It was probably around this time that Falchetti gave Sargent an oil sketch of a glacier (a subject particularly important to Segantini and his followers), dated 1905, which appeared in the artist’s estate sale of July 1925.

The two artists left for Palestine on 9 September 1905, a week later than originally planned. ‘I put off my departure for a week,’ Sargent wrote to his friend Mrs Charles Hunter on 8 September from Turin, ‘for the sake of starting with an Italian artist who is going along and could not get away till tomorrow’. Falchetti would return from Palestine in early December, nearly two months before Sargent, because he needed to finish Alpine View for the upcoming show in Milan.

Sargent’s choice of Falchetti as his companion proved to be a happy one. As Sargent wrote to Mrs Hunter, ‘Falchetti is an ardent catholic which may be entertaining’ and the Italian artist may have helped Sargent enter into the mystical spirit of the holy sites, particularly those that were the location, according to the Gospels, of the miracles performed by Christ. Thanks to the help of a cardinal friend of Falchetti – probably Agostino Richelmy, who was the Archbishop of Turin – the two companions were able to visit monasteries in the heart of Palestine that were rarely open to foreigners. Sargent’s unpublished letters to Mrs Charles Hunter (now in the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University) are evidence of a growing friendship between the two painters during the trip, a friendship fostered by common interests: ‘My companion is a great success,’ wrote Sargent on 1 October; Falchetti, he added, is an ‘excellent musician, fair chess-player – all this is good for days that are getting short – the sun sets here before 6 & it gets dark right away’.

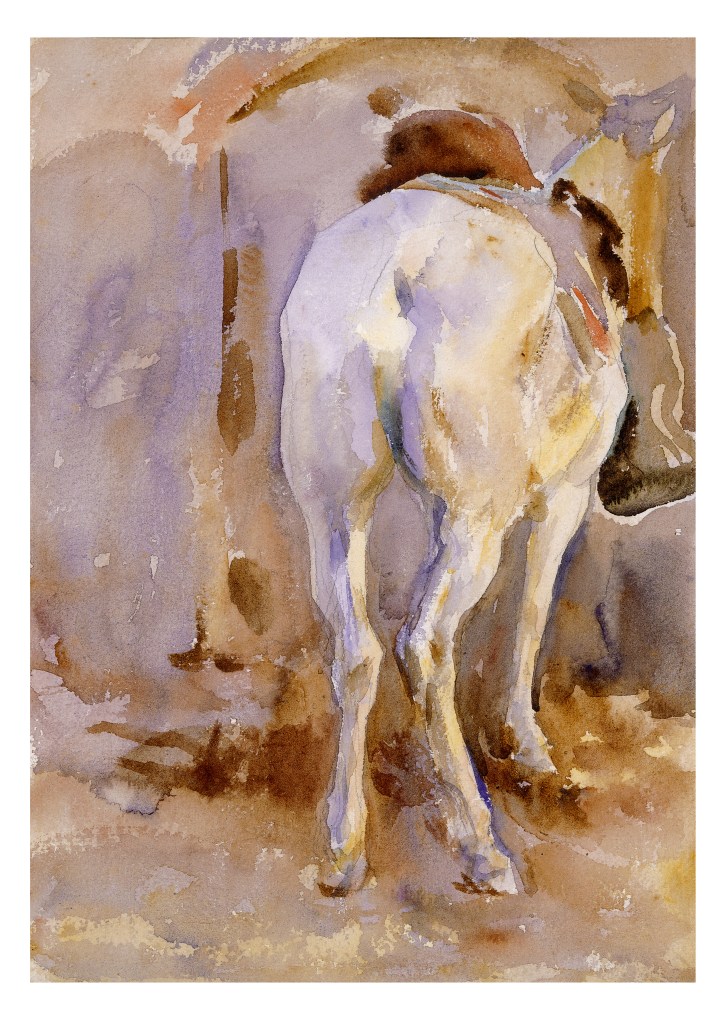

During their trip to Palestine, Falchetti broke with his existing style and began experimenting in a more Impressionist manner. A watercolour of a mule viewed from behind is almost identical to one painted by Sargent, and demonstrates the Italian’s dependence on the style and technique of his more experienced companion. Sargent wrote to Falchetti’s brother Ernesto from Palestine about Alberto and about their trip: ‘I am happy to know that his letters demonstrate his happiness, and I have not doubted. The life that we have here, all work, and outdoors, is the life he loves – he exhibits excellent health and good spirits. I am happy to have a friend like him.’

Falchetti and Sargent arrived in Jerusalem between the middle and the end of September 1905. In an article published by Falchetti in La Stampa in November, he writes that after landing at Jaffa he and his companion took a train to Jerusalem where ‘lots of people sent by Consul Cok [?] were waiting for us’. Here the two stayed in the luxurious Grand New Hotel. In the same article, Falchetti recorded a trip to the valley of the Mar Saba and to the Dead Sea. He wrote of the valley that it ‘looks like a tripled version of the Roman Colosseum: an amphitheatre with large steps […] where, a long time ago, lived thousands of Greek eremites who were later massacred by the Turks. No doubt they lived in an inhospitable and arid land.’ Falchetti continued: ‘In the middle of that valley is a wonderful building stuck in the rock with high walls and huge rocky steps. This is the monks’ hermitage of punishment. It is a quiet area […] the dragoman with us found the gaoler who seems a sort of dazed ghost, and we went in to the monastery.’

Falchetti and Sargent then went across the valley and painted watercolours looking at the monastery from across the chasm, but only a work by Sargent seems to have survived. Falchetti recalled the emotions he and his companion experienced at the site in which, according to the sacred scriptures, Jesus ascended into Heaven:

At a stroke, there opened to our gaze a marvellous spectacle of the infinite descent of the mountains to the Dead Sea, which we saw shining like a topaz in the light of the setting sun, fed by the river Jordan, which arrives direct and shining like a blue ribbon.

It was from this high ground that Falchetti produced a sketch for a painting later exhibited at the Promotrice of Turin in 1906, titled The Dead Sea seen from the Judaean Mountains – the location of which is unknown– and Sargent painted his masterly The Mountains of Moab which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1906, and was very possibly intended as a source for the landscape in the never-to-be-completed Sermon on the Mount in Boston Public Library. Sargent’s panoramic desert scene, which follows the course of distant hills falling away along the horizon (an unusual composition for Anglo-American taste), seems to recall the mountain landscapes Falchetti was fond of painting. In particular it seems to have been inspired by the large scene Falchetti was painting in Giomein, a work that had certainly captured Sargent’s attention when he saw it.

After the trip to the Holy Land, the bond between Falchetti and Sargent seems to have grown deeper. Several meetings are documented between 1906 and 1909, and they corresponded more frequently. In April 1906, for example, Sargent sent to Falchetti a selection of photographs from the murals in the Boston Public Library, including ‘two fragments of a decoration – Astarte, and a bad photo of the bas-relief, The Redemption’. The two artists met in the summer or maybe the autumn of 1906, when Sargent spent some time in Turin in Falchetti’s company, as well as in the summer of 1907, when together with Pollonera, Raffele and Stratta, they painted figurative scenes, with models posing along the stream at Peuterey in the Val d’Aosta. Falchetti returned to Caluso, or maybe to Turin, at some point that summer, and returned to the Val d’Aosta in mid September for a further three days. Perhaps it was during this summer of 1907 that he ‘copied’ all that Sargent painted, as Raffele wrote in a postcard to his friend Marco Calderini. Among the ‘copies’ was one of Sargent’s well known pictures, Val d’Aosta (c. 1907) in the Tate collection, depicting Mont Blanc as seen from Val Veny. The two canvases are nearly the same size, show the same view and share a similar style of painting, although Falchetti’s brushstrokes are firmer than those of the impulsive and impressionistic Sargent. It is possible that Falchetti’s picture was an original work, rather than a copy, painted alongside Sargent.

Falchetti would certainly have appreciated the mystical and Romantic aspects of his friend’s picture. His own mountain landscapes became increasingly concerned with the sublime, replacing the chromatic equilibrium of his earlier work with dramatic storms, a sign of his emotional engagement with nature. This is demonstrated in his painting Mountain Hurricane, today housed in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, a sketch of which is preserved in a private collection in Piedmont, and in another painting titled Alpine Cliffs, which Sargent praised in a letter to Falchetti of 1909:

I am happy to see from the photo attached that the painting (with a mountain) is going well. I like it very much, it is well composed. I found that the light, the background and the clouds are excellent. In particular, I am glad that the painting seems to be strong in the back and foreground: sometimes the painter seems to take care only of the sky and the remoteness. It seems that there is a terrible hurry to take refuge in the blue sky. Sweet refuge from the dangers.

The artists remained in touch, but do not appear to have met again – although Sargent talked of visiting his friend’s mountain eyrie in 1908. Falchetti did not join Sargent’s party at the Simplon Pass in the summer of 1909 which included Raffele, Stratta and Pollonera, and the two men seem to have drifted apart. And after 1910, in works such as In alta pace. Tramonto (c. 1912), there seems to be a recurrence of Segantini’s influence in Falchetti’s painting. But, for a short and intense period of time, Sargent and Falchetti had exercised a significant influence on each other’s art.

From the July/August issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.