There’s an irony to how minimalism – generally understood as a philosophy of simplicity – has such a plurality of meanings and moments. Alongside minimalist art, minimalist music and minimalist architecture sit minimalist product design and, in the last decade, a minimalist-lifestyle blogging movement. In The Longing for Less, cultural critic Kyle Chayka surveys this disparate landscape alongside what he argues are its foundations in Buddhist philosophy and thousand-year-old Japanese aesthetics, and asks, what might be the essence of minimalism? And what are the lessons it might impart on how to live with the objects in our lives?

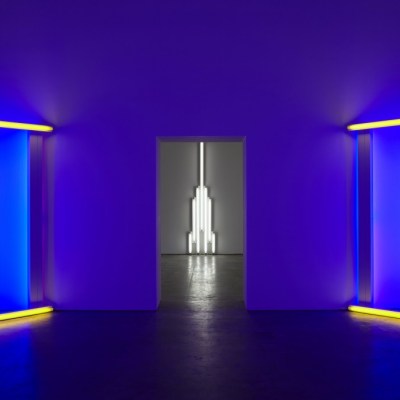

Chayka describes how minimalism emerged in the early 1960s in New York City, where a generation of artists started to use the industrial materials and hard, geometric vocabulary of modernist architecture, yet with the antithesis of modernism’s utilitarianism. Agnes Martin drew precise, rectilinear grids; Dan Flavin made light sculptures out of fluorescent lighting tubes; Donald Judd arranged industrially fabricated boxes of concrete and aluminium on gallery floors. This wasn’t art that was ‘for’ anything: it did not represent, it did not symbolise. ‘All I want anyone to get out of my paintings […] is the fact that you can see the whole idea without any confusion,’ said Frank Stella in 1966. ‘What you see is what you see.’

Chayka describes how minimalism emerged in the early 1960s in New York City, where a generation of artists started to use the industrial materials and hard, geometric vocabulary of modernist architecture, yet with the antithesis of modernism’s utilitarianism. Agnes Martin drew precise, rectilinear grids; Dan Flavin made light sculptures out of fluorescent lighting tubes; Donald Judd arranged industrially fabricated boxes of concrete and aluminium on gallery floors. This wasn’t art that was ‘for’ anything: it did not represent, it did not symbolise. ‘All I want anyone to get out of my paintings […] is the fact that you can see the whole idea without any confusion,’ said Frank Stella in 1966. ‘What you see is what you see.’

In 1965, the British philosopher Richard Wollheim noted the ‘minimal art-content’ of the work, observing that it lacked all the qualities, from the hands-on touch of the creator to a gesture at the transcendent, that were normally seen to elevate an ordinary object into the realm of art. Chayka sees this not simply as a matter of ‘reduction’, but of a deeper ‘emptiness’ at the core of the work: ‘The artists were revolutionary not because of a shared homogenized style but because of a particular leap that they made: The art object did not have to represent anything, document reality, or even communicate the artist’s individuality. It was enough to generate a presence, to become part of the world […] Sensation replaced interpretation.’ Artworks that many might find difficult to engage with are, in this way, made thrilling.

The 2010s saw a dramatic resurgence of minimalism – occurring not in the artistic avant-garde but the most popular side of design. Responding to the post-recession mood, a cohort of largely American lifestyle bloggers argued that the problem was that people had too much stuff. Joshua Becker began his blog Becoming Minimalist in 2008, and in 2011 ‘The Minimalists’ (Joshua Fields Millburn and Ryan Nicodemus) quit corporate careers and self-published Minimalism: Live a Meaningful Life, evangelising about how they ‘jettisoned most of their material possessions, and started focusing on what’s truly important’.

If the austerity of the early 2010s lifestyle-minimalism was influenced by minimalist art, it was only the work of the architect John Pawson as viewed through his Calvin Klein store. Its primary inspiration came from brands: lifestyle bloggers combined the glass and gleaming white Noughties glamour of Apple with a dash of ’90s fashion (Donna Karan’s ‘capsule wardrobe’) as evidence that fulfilment lay in owning less. Another minimalist blogger, Dave Bruno, championed a 100 Thing Challenge, seeking to ‘unhook himself from consumerism by winnowing his life’s possessions down to 100 things in one year’.

Although ‘It’s easy to feel like a minimalist when you can order food, summon a car or rent a room using a single brick of steel and silicon,’ Chayka reminds us that the iPhone that allows us to do this depends on a vast and ugly assemblage of earth minerals, undersea cables, and low-waged labour. He criticises lifestyle-minimalism for allowing us to pretend that a better relationship with capitalism is as simple as a matter of individual choice.

Chayka’s heart clearly lies with the perception-testing works of minimalist artists – though, as a young writer living (at time of writing) in a small apartment in New York, he acknowledges he might also be a lifestyle minimalist by necessity. Despite Chayka’s stated intent to ‘bypass the superficial minimalist style’, these two conflicting minimalisms keep meeting throughout his book. The resultant collisions make the book genre-defying (bookstores are shelving it as everything from literary arts to self-help, or home and garden), but productive.

In New York, Chayka explores Donald Judd’s loft on Spring Street and Walter de Maria’s Earth Room (1977) at 141 Wooster Street, both in Soho – a district that was even in the 1970s emerging as a hub of the luxury minimalist design-consumerism critiqued two chapters before. In 1973, Judd decamped to the remote, desert town of Marfa in West Texas to escape this ‘Soho lifestyle’ – and gain the space and setting to make larger and more permanent sculptural works. The town was a quiet cattle-ranching outpost with little in the way of furniture retail, and so Judd commissioned local carpenters to make the furniture he needed. Today the Judd Foundation manufactures and sells these design products with a chair costing $2,100 and a desk $9,000. Soho has come to West Texas complete with sleek hotels, glass box modernist vacation homes, and of course, a simulacrum of a Prada store. It might really be a 2005 installation by the Berlin artists Elmgreen & Dragset, but the Instagrammers largely take it at face value.

Nonetheless, Chayka believes that, ‘In minimalism’s origins, and in the objects artists like Judd left behind, it is still capable of breaking down the layers of money, taste, and marketing that separate us from pure sensation.’ One morning he walks out into the Marfa scrubland to view 15 Untitled Works in Concrete (1980–84). A line of huge, rectangular concrete boxes – 15 groups in compositions of threes and fours, each box five metres on a side – repeats as if to the horizon. The scale is geological, the execution precision engineered, the experience bodily. The rhythm of the composition, its iteration and variation, unfolds gradually at walking place, the installation not viewable as a whole except from a low hill on the far side. The sun beats down. The interior of the boxes provides cool, dark relief.

‘Shadows’, this play of light and dark, are the fourth quality (after ‘reduction’, ‘emptiness’, and ‘silence’) Chayka identifies as the essence of minimalism. He finds it best expressed in Japan, not only in Junichiro Tanizaki’s book In Praise of Shadows (1933) but as a wider principle of ‘accepting ambiguity, understanding that opposites can be part of the same whole’. He describes two 11th-century works, The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon, lady-in-waiting to Empress Consort Teishi and The Tale of Genji by her contemporary Murasaki Shikibu, both of which value the shrouded and the glimpsed rather more than straightforward modes of speech or perception.

Still from Tidying Up with Marie Kondo (2019). Courtesy Netflix

It’s perhaps this affinity for ambiguity that explains why Chayka takes against that other Japanese minimalist, Marie Kondo. She is after all an advocate of order and ‘everything in its place’, rather than the artfully imperfect, and Chayka finds this approach ‘rigid’. Kondo may let a person choose which objects may stay in their home, ‘but she tells you exactly how it should be folded, stored, and displayed – in other words, how you should relate to it’. For Chayka, who has found in minimalist art and music a space of ‘unmediated experiences’ and ‘giving up control instead of imposing it’, this is antithetical.

Whether the objects in our lives can or should have meaning is a question that both minimalisms, art and lifestyle, grapple with to varied effect. In response to critique (from authors including Chayka), the lifestyle bloggers have sought to reposition their minimalism as ‘not even about possessions’, but rather meaning, and living ‘a more intentional life’. Yet nonetheless they insist that meaning cannot reside in things, only people – and so the appropriate attitude towards things remains reduction.

Chayka groups Marie Kondo with these lifestyle-minimalists, but I am not sure this is entirely fair. Watching Tidying Up with Marie Kondo on Netflix (2019), what stands out is the reverence she has for things. She greets each home with a few moments of meditation or prayer, thanking it for offering shelter. Each garment to be discarded is first thanked for its service, and for those that are kept, her famed folding technique is a practice of reverence. In The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up (English edition 2014), Kondo described how she was a regular visitor to her community’s Shinto shrine as a child, and spent five years as a miko or shrine maiden, a role entailing care for the shrine and its grounds. Shinto includes the belief that kami (the sacred) exists in everything, and tsukumogami, the concept that inanimate objects can gain a soul after one hundred years of service. Through tidying, Kondo seeks to ‘make room for meaningful objects, people and experiences’ – not cast them out at all.

Judd’s ‘specific objects’ meanwhile demand that meaning is found in their existence as things – they are in no way metaphorical, such that all that exists to communicate is their objecthood itself – yet they refuse easy recognition. One encounters these objects, but they do not necessarily speak. Chayka introduces us to Bill Dilworth, who has been docent and caretaker of De Maria’s Earth Room for the last 30 years. ‘People come up and ask me what it means,’ he says. ‘I really just turn them back to the Earth Room so they can look for the answer.’

The Longing for Less is a more forthcoming guide. Through its meditations on experience, attention and ambiguity, minimalism is no longer a matter of reduction but is vastly expanded: it becomes a way to encounter the world.

The Longing for Less: Living with Minimalism by Kyle Chayka is published by Bloomsbury.