The art of William Russell Flint continues to divide opinion, long after his death, which occurred 50 years ago this month. Undoubtedly the most accomplished watercolourist of his day, he handled this notoriously testing medium with an ease and assurance which achieved the near impossible: a perfect balance of expressivity and control. In the 1920s, when he freed himself from his long apprenticeship, first as a visual reporter for the Illustrated London News, then as the illuminator of a host of classic texts in lavish, colour-plate editions, he was hugely successful. He won prizes in international watercolour exhibitions, he was the subject of numerous books and articles, and he quickly entered national public collections both in London and overseas. The majority of critics, however, were less easily won over. His work was ‘intolerably trite’, ‘facile’, or worse.

If ever there was an artist for whom familiarity came to breed contempt in the eyes of the post-war generation, Russell Flint is, unfortunately, an obvious candidate. In the 1950s and ’60s, high-quality colour reproductions of his watercolours saturated suburban houses the length and breadth of the country. He was so safe a choice and so ubiquitous that the subjects of his pictures became almost invisible. Towards the end of 2020, the Royal Watercolour Society is due to open new premises in Whitcomb Street, next to the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square. With watercolour in the spotlight – a medium I have a long association with as a curator and scholar – what of the status of the Society’s former president and most conspicuous advocate? This seems like the moment to reconsider a figure unjustly ignored by art history.

The Bathers’ Arcade (c. 1922), William Russell Flint. Ⓒ the artist’s estate

The 1920s can claim to be the high point of British watercolour painting. And at a time when post-war reconstruction was almost obsessed with rediscovering or redefining the national character, Russell Flint encouraged his countrymen and women to look overseas; Scottish by birth, he avoided almost any involvement with England, as either image or ideal.

In 1921, he travelled for several weeks in Spain. There was an understandable fascination with the country that had remained neutral during the First World War; far from the cataclysm endured by the combatant nations, here was a way of life almost unchanged for centuries. Flint was not interested in the simply picturesque. He was sympathetic to the widespread poverty of rural communities engaged in their own battles for survival. Well aware of how Augustus John had embraced the character of the gypsy to express the ambiguity of his feelings as an outsider within the establishment, Flint proposed real gypsies, studied, as ever, from life.

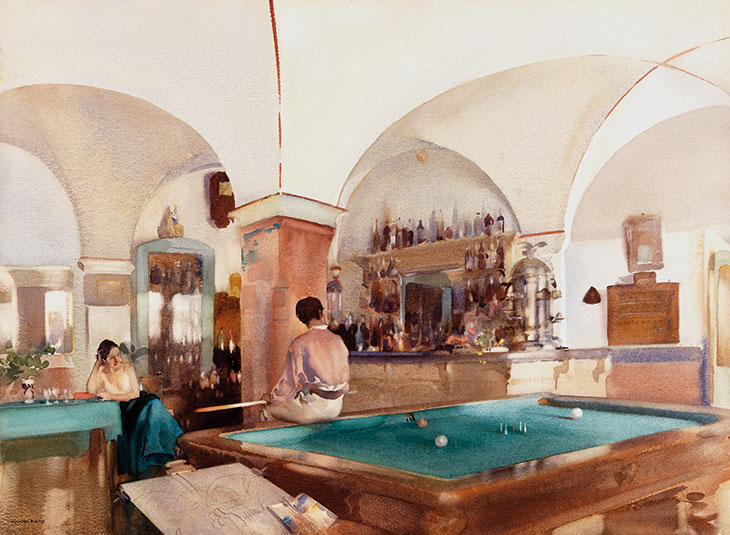

Flint shares with Picasso – an unlikely pairing, I grant – an acute self-awareness, a constant need to put himself into the picture. My favourite example of this has to be Flint’s Billiard Bar, Laigueglia, painted, so the artist recalled, one rainy day in the tiny Ligurian coastal resort west of Genoa. The assembly of bottles on the counter is a marvel in itself, but a mere backdrop to the Chekhovian drama of waiting and unconnectedness portrayed by the two figures. Between them, in the very foreground, we eventually spot the artist’s unfinished sketch, fixed to his drawing board beside his little watercolour box. This casual, inconsequential slice of life turns out to be staged, and Flint, its producer/director, could not resist a walk-on role.

Billiard Bar, Laigueglia (1926), William Russell Flint. Courtesy MacConnal-Mason Gallery, London; © the artist’s estate

Flint’s years as an illustrator gave him an instinct for narrative. Having attended society events on behalf of the Illustrated London News, he became attuned to women’s fashion, and looked at the pages of French Vogue to gauge the latest developments in Paris. More than a residue of French glamour survives in the groups of female bathers he produced in the early 1920s. The Bathers’ Arcade, perhaps the finest of them, does not shy away from the artificiality of the fashion plate. It recognises that sunbathing is the latest fad of a wealthy elite, but the pose of the central woman, covering her breasts at the quizzically disapproving stare of the young girl, speaks volumes about the social and moral boundaries such behaviour exposes, even among a community exclusively of women. While the health benefits of heliotherapy were becoming well known, gymnosophy – as nudism was termed, with deliberate obfuscation, in Britain – was regarded with deep suspicion by the general population. Havelock Ellis, one of its most vocal supporters, was a thorn in the side of the buttoned-up British in this, as in many other respects. His seven-volume Studies in the Psychology of Sex could not even be published in Britain for its supposed danger to public morality.

In 1926, two years after the first Winter Olympics in Chamonix included cross-country events for competitors of both sexes, Flint made a series of watercolours of women skiing. Women’s participation in sport was one of the most conspicuous social developments of the time, recognising that the individual’s right to her own physicality could no longer be confined to childbirth and the family. Large tracts of untouched white paper are shaped into mountainsides by the flimsiest of washes. It is tempting to read into all this virgin snow something of the painter’s subconscious desires, well-mannered Scottish Presbyterian though he was.

Between the wars, there was no major artist who did not exhibit work in watercolour, and some – Paul Nash is the outstanding example – produced far more watercolours than oils. In the 1950s Herbert Read remarked that one of the reasons for the recent demise of serious watercolour art was that it was simply too impregnated with notions of Britishness at a time when artists wanted to engage with international movements. Russell Flint, a watercolourist who in almost every other respect is decidedly un-British, certainly demands reconsideration, and not purely as a historical footnote. His art is complex, ambiguous, deeply personal and yet entirely representative of the tensions between the present, the past and the future which typified the interwar years. In looking again at this once most popular of artists, there is much to be learned – not only about a forgotten exponent of a sometimes minor art, but also about the public who gave him his phenomenal success.

From the December 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.