The Wallace Collection is one of London’s most treasured museums and, inexplicably, one of its least crowded. Its home – for this is a home-turned-museum – is Hertford House, a much remodelled, red-brick mansion that dominates Manchester Square and fills an entire city block. It was originally built between 1776 and 1788 for the 4th Duke of Manchester, its location chosen because there was good duck-shooting nearby; today, its imposing but frankly unlovely exterior, most of which dates to the 19th century, belies the importance of the holdings within. This is a collection renowned for the quality of its 18th-century French furniture and porcelain, and for its outstanding Old Master paintings, which include The Laughing Cavalier, A Dance to the Music of Time by Poussin and Fragonard’s The Swing. Those fabulously wealthy connoisseur-collectors, the 3rd and 4th Marquesses of Hertford, have long been celebrated for such acquisitions.

Yet these masterpieces are only part of the collection and its story. The unsung hero here is Sir Richard Wallace (1818–90), the unexpected heir to the 4th Marquess. Not only did Wallace make his own distinctive contribution to the collection that he inherited, but he also ensured that it would be enjoyed by the public in their millions. In 1872, the inaugural exhibition at the Bethnal Green Museum in the East End of London, which included some 2,000 pieces lent by Wallace, was seen by more than two million visitors; in 1897, on the death of Lady Wallace, the collections displayed at Hertford House – all 5,637 objects – were left to the British nation. No single gift of works of art has ever been more generous. This summer, to mark the 200th anniversary of Wallace’s birth, the museum is turning the spotlight on this enigmatic figure (with the exhibition ‘Sir Richard Wallace: The Collector’; until 6 January 2019).

The Horn of St Hubert (late 15th century), Southern Netherlands or France Photo: © The Wallace Collection

Wallace’s life – his illegitimate birth, extraordinary inheritance, and personal tragedy – was the stuff of a Victorian novel (the dissolute 3rd Marquess of Hertford, the man who may well have been his grandfather, was the inspiration for the sinister Lord Steyne in Vanity Fair and Lord Monmouth in Coningsby, a novel by Benjamin Disraeli). Our character was born Richard Jackson, the son of one Mrs Agnes Jackson (née Wallace). She abandoned her seven-year-old son in Paris in 1825, allegedly during a visit to Richard Seymour-Conway, the future 4th Marquess. Accounts differ wildly, but it seems that Seymour-Conway’s mother, Maria, Marchioness of Hertford (known as Mie-Mie), took a shine to this beautiful child, and is said to have recognised the features of her elder son in him. Still mourning the death of her daughter Frances a few years before, she took the boy in; he remained close to Mie-Mie and her two sons for the rest of their lives.

It was always presumed that Wallace – he had himself baptised as such in 1842 – was the illegitimate son of Lord Hertford (as Seymour-Conway became in the same year). The unmarried peer denied this, describing himself as barren and childless, and his paintings as his progeny. In a codicil to his will, however, he left his collections and the greater part of his unentailed wealth to Wallace, rather than to the distant cousin who succeeded him to the marquessate: ‘to reward as much as I can Richard Wallace for all his care and attention to my Dear Mother & likewise for his devotedness to me during a long and painful illness I had in Paris in 1840 & in all other occasions.’

With no conclusive evidence, the jury is still out. Suzanne Higgott, author of a thorough new biography, Sir Richard Wallace: Connoisseur, Collector & Philanthropist (forthcoming, Pallas Athene), believes Hertford’s paternity likely. Either way, it seems plausible that he recognised that Wallace, who had proved to be a knowledgeable connoisseur and had long acted as his most trusted agent, would be the ideal custodian of his beloved works of art.

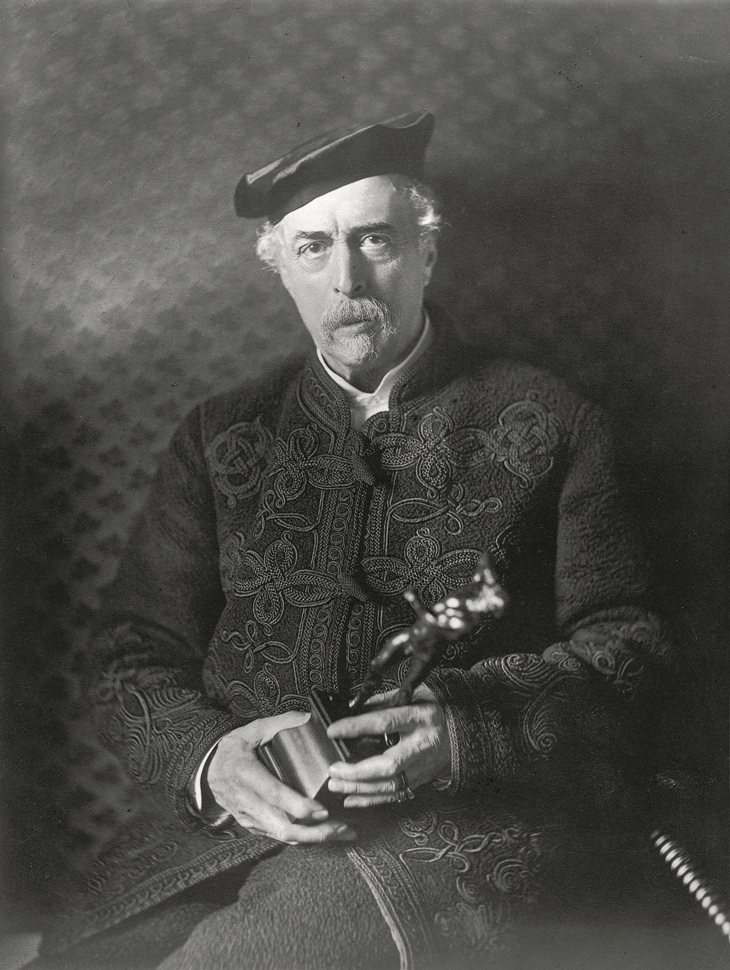

Sir Richard Wallace, 1st Bt (1888), John Thomson. National Portrait Gallery, London

For a British aristocratic family with vast estates in England and Ireland, the Hertfords were unusually Francophile. The 1st Marquess had served as ambassador to France between 1763 and 1765; the 3rd Marquess, profiting from a country in turmoil, bought freely from the great aristocratic collections dispersed during and after the French Revolution. His son, the future 4th Marquess, grew up in Paris, his mother choosing not to live in England with her roué of a husband. That she was knowledgeable about art is evident from her letters, and her two sons became prolific collectors with a penchant for French art, old and new (her second son, Lord Henry Seymour, had been conceived when her husband was in England). The elder chose to live in the exquisite Château de Bagatelle in the Bois de Boulogne, where he died in 1870. In his upbringing and education, Wallace was more French than English.

After his father’s death in 1842, the 4th Marquess began to collect in earnest. The 24-year-old Wallace became one of his agents, acting on his behalf in salerooms and travelling widely in pursuit of works of art. He evidently learned a great deal from his mentor. His own taste at this time is revealed in the works that he bought for himself but was obliged to sell in 1857, mostly as a result of losses on the stock exchange. The lots in the Richard Wallace sale – 320 objets d’art and 152 paintings, acquired with his allowance – reflect the interests of both Hertford and Seymour: 18th-century gold boxes, Sèvres porcelain, miniatures, semi-precious hardstones, arms and armour, and contemporary French paintings and sculpture. Nonetheless, already discernible is a predilection for small-scale and exquisitely worked pieces, and for the medieval and Renaissance works of art that were then the subject of growing interest in France.

Miniature altarpiece (early 16th century), Netherlands. Photo: © The Wallace Collection

Wallace’s influence on Hertford’s acquisitions grew. As Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild wrote in his manuscript memoir Bric-a-Brac (1897), the 4th Marquess was in Wallace’s debt ‘for not a small proportion of his works of art, nor the least valuable of them. The knowledge and taste of the pupil were equal to those of the master; and, indefatigable in his exertions, M. Richard was ubiquitous. Whenever there was a public sale on the Continent, M. Richard was on the spot; when some special object was to be obtained in England, Mr Wallace appeared. His judgment was impeccable.’ In the later years of Hertford’s life, Wallace may well have been the driving force behind many, if not most, of the purchases for the collection.

It is not entirely clear why Wallace decided to return to England in 1871. His generosity in helping the English community in Paris, as well as the French who had suffered appalling hardships during the Franco-Prussian War (particularly during the Siege of Paris), had earned him both a baronetcy from Queen Victoria and the Légion d’honneur that year. Perhaps he thought, not unreasonably, that the collections would be safer in London. After coming into his inheritance, he had married his long-term mistress, Julie Amélie Charlotte Castelnau, whom he had reputedly met when she worked in a perfumier’s shop, legitimising their son Edmond, born in 1840. What is clear is that he threw himself enthusiastically into the task of adding to the collection and arranging its display at Manchester House, which he had renamed after his benefactor. He enhanced existing holdings and formed new ones.

Partial armour (c. 1570–90), Lucio Marliani, called Piccinino. Photo: © The Wallace Collection

Where Wallace differed from the 3rd and 4th Marquesses was in a passion for medieval and Renaissance works of art – which meant everything from ivories and enamels to Venetian glass, but particularly Italian maiolica, sculpture and European arms and armour. Indeed, he formed what is arguably the finest collection of richly decorated princely armour in Britain. Like his probable antecedents, however, his buying was opportunistic.

Almost immediately, the comte de Nieuwerkerke, who was the former surintendant des Beaux-Arts under Napoleon III and had fled to London in 1870, offered Wallace his entire collection. Comprising some 800 examples of medieval and Renaissance decorative arts and princely arms and armour, it was the first of several purchases made en bloc, and probably prompted Wallace to enlarge Hertford House. It was not uncommon for him to make several, often quite disparate acquisitions daily.

More arms and armour soon followed, from collections such as that of Sir Samuel Rush Meyrick, revered as the father of the academic study of this specialist field of metalwork. Perhaps most spectacular here is the virtuoso half-armour almost certainly made around 1570–90 by the greatest goldsmith-armourer of the day, the Milanese Lucio Marliani, known as Piccinino. So extensive and elaborate is its decoration that no plain metal is visible; almost every technique available to the Renaissance metalworker was employed. Hercules and the Nemean lion, Roman heroes, allegorical figures and mythical beasts come together in a fantastical decorative setting that combines embossing, chasing, gilding, silvering and inlay in both gold and silver.

Dish depicting women bathing (1525), workshop of Maestro Giorgio Andreoli, central scene attr. to Francesco Xanto Avelli da Rovigo. Photo: © The Wallace Collection

To the 30 pieces of Renaissance maiolica acquired from Nieuwerkerke, Wallace soon added more than 100 further examples of this colourful, tin-glazed earthenware. Most are istoriato wares, ornamented with narrative scenes drawn from classical mythology. One tour de force is the monumental lustred dish, proudly proclaiming that it was made in the workshop of Maestro Giorgio Andreoli in Gubbio in 1525, its central scene probably painted by the finest and most ingenious maiolica painter of them all, Francesco Xanto Avelli da Rovigo. The subject, women bathing in an elaborate classical cistern before a distant town, is characteristically borrowed from various engravings by Marcantonio Raimondi.

In 1872, Wallace acquired 57 lots from the Allègre sale in Paris, the most unusual among them a pair of gold wine cups with an iridescent blue ground, made using kingfisher feathers in the traditional Chinese technique of tian-tsui, and ornamented with precious stones and pearls. At least one of them was used by the Qianlong Emperor to celebrate the New Year in the Summer Palace in Beijing.

Ceremonial wine cup (18th century), China. Photo: © The Wallace Collection

These cups suggest a taste for exoticism, as does another great rarity, the Buddha-like Christ as the Good Shepherd, sculpted in rock crystal and adorned with gemstones, which was made in Goa or Sri Lanka in the second half of the 16th century. In 1874, Wallace also acquired what must at the time have been regarded as curiosities: 16 gold objects from the treasury of King Kofi Karakari of Asante (in modern-day Ghana), seized by the British during the Third Anglo-Ashanti War in 1873. Of these, the remarkable 19th-century gold mask is the largest-known historical gold object to have been produced in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Trophy head (19th century or earlier), Africa. Photo: © The Wallace Collection

Wallace’s tastes were eclectic. As well as bolstering the holdings of 17th-century Dutch painting and contemporary French art, he acquired anything from quaint wax portraits to 15th-century Italian paintings, drawings and illuminated manuscripts gathered by vicomte Both de Tauzia, curator at the Louvre. Among the latter was the fresco fragment of around 1464, The Young Cicero Reading, by the Lombard master Vincenzo Foppa – the sole remains of a cycle commissioned by Cosimo de’ Medici for the Banco Mediceo in Milan. To the superlative, mostly 17th- and 18th-century French sculpture in the collection, Wallace added the likes of an extraordinarily elaborate and intricately carved boxwood or pearwood miniature tabernacle altar made in the Southern Netherlands in the early 16th century. His last acquisition, made in 1888, appears to have been Barthélemy Prieur’s Acrobat, a novel and engaging bronze figure standing on his hands, cast around 1600.

Yet there was also a Romantic, antiquarian aspect to Wallace’s collecting. In 1879, for instance, he acquired the extraordinarily rare Bell of St Mura. This hand bell and shrine is believed to have come from the Abbey of Fahan in County Donegal, founded in the 7th century by St Mura. The bronze body of the bell, with its original Celtic decoration seen in one corner where later casing has been detached, was probably crafted at Kells, the great centre of art and monastic life in Ireland. Its silver filigree and cast plaques, rock crystal and amber stones, added at various time between the 11th and 16th centuries, are testimony to the reverence in which it was held.

The Bell of St Mura (11th–16th centuries; body: late 11th century), Ireland (Kells?). Photo: © The Wallace Collection

In the same year Wallace acquired the Horn of St Hubert, among the relics of the 8th-century saint said to have converted to Christianity after seeing a vision of Christ on the Cross between the antlers of a stag while out hunting. Legend has it that in 1468 this horn was given to Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, by the Bishop of Liège, and later housed in the chapel dedicated to St Hubert founded by the duke at Chauvirey-le-Châtel.

An illustrious provenance was certainly appealing to Wallace, just as it had been to the 4th Marquess. No doubt one of the reasons why, in 1875, he paid a princely £4,500 for a monumental maiolica wine cooler from the Urbino workshop of Flaminio Fontana was because it was made for Cosimo de’ Medici, whose device it bears. Another prized trophy was the parrying dagger made for Henri IV of France and carried by Napoleon. Not every grandiose provenance has passed the test of time. Cardinal Mazarin’s gold and bloodstone cutlery set, for one, turned out to have been made in the 18th century. Wallace also bought the odd fake, as well as some pastiches – but given the quantity of clever deceptions circulating in the market in the late 19th century, he fared surprisingly well.

Acrobat (c. 1600), attrib. to Barthélemy Prieur. Photo: © The Wallace Collection

As the 1870s progressed, Wallace’s purchasing slowed down to a trickle, all but stopping in the 1880s. Like every landowner in Britain, he was affected by the agricultural depression. It is tempting to feel that he was also broken-hearted. History had a way of repeating itself in the Hertford/Wallace menagerie: Wallace’s son Edmond had taken a mistress, by whom he had four children, born between 1872 and 1878, but he had become estranged from his father after refusing to leave his family. When Wallace wrote his will in 1880, he left his son only a single property in Paris, and all dynastic ambition was lost when Edmond died at the age of 46 in 1887.

Wallace spent much of the last three years of his life in Paris and died, like the 4th Marquess, at Bagatelle, in 1890. His legacy is the remarkable collection that Lady Wallace, in her bequest of 1897, insisted should never be changed or leave Hertford House. To ensure access for all when part of the collection was first shown in the East End in 1872, the Bethnal Green Museum was free for three days a week, when it was open until 10pm. After the first free day, the arts administrator Sir Henry Cole noted in his diary: ‘More than 25,000 persons. Dirty, & pleased & orderly.’ Today, admission to Hertford House is free to all visitors, still pleased and orderly – but rarely in need of a bath.

‘Sir Richard Wallace: The Collector’ is at the Wallace Collection, London, until 6 January 2019.

From the June 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.