With the opening of the Watts Studios, one of the most remarkable turnarounds in any Victorian artist’s reputation is almost complete. Who could have guessed only 15 years ago that George Frederic Watts would be so comprehensively rescued from the condescension of posterity? Acclaimed as Britain’s greatest painter when he died in 1904 at the age of 87, his eclipse was all but total. As the in-house artist of the Victorian intellectual aristocracy that gave birth to the Bloomsbury Group, he was singled out for particular ridicule by Virginia Woolf among others; in the 1930s the Tate Gallery dismantled the room devoted to his work. Underfunded, understaffed, and undervisited, the best collection of his paintings, at the Watts Gallery in his home village of Compton in Surrey, slid into picturesque decay.

Watts’s return to public esteem owes much to four factors: a revaluation of late Victorian art in its international context, an outstanding exhibition, the revitalisation of the Watts Gallery, and – largely as a consequence – a reassessment of Watts’s wife, Mary, as an independent artistic personality. The aspect of Watts’s art that most appealed to his high-minded admirers in his lifetime, his allegorical or philosophical subjects, such as the endlessly reproduced Hope (1886), was an important reason why his reputation plummeted in the general reaction against Victorian moralising. Yet it’s precisely this aspect of his work that has led art historians to argue that Watts, together with such contemporaries as Burne-Jones, can be understood as part of mainstream European Symbolism.

However, even his greatest admirers agree that Watts’s work needs sensitive and knowledgeable editing. That is precisely what he got in a centenary exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in 2004, ‘G.F. Watts Portraits: Fame & Beauty in Victorian Society’, curated by the leading Watts scholar Barbara Bryant. To visitors who thought themselves allergic to his work – I was one – this discriminating selection came as a revelation.

In the same year, Perdita Hunt became director of the Watts Gallery, and a renaissance began in Compton. With a £4.3 million grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund, Hunt and her trustees embarked on a comprehensive programme of repair and modernisation. The Gallery reopened to the public in 2011, watertight at last, with a dedicated exhibition space and a conserved collection of 250 paintings, some 800 drawings, and Watts’s models for sculpture.

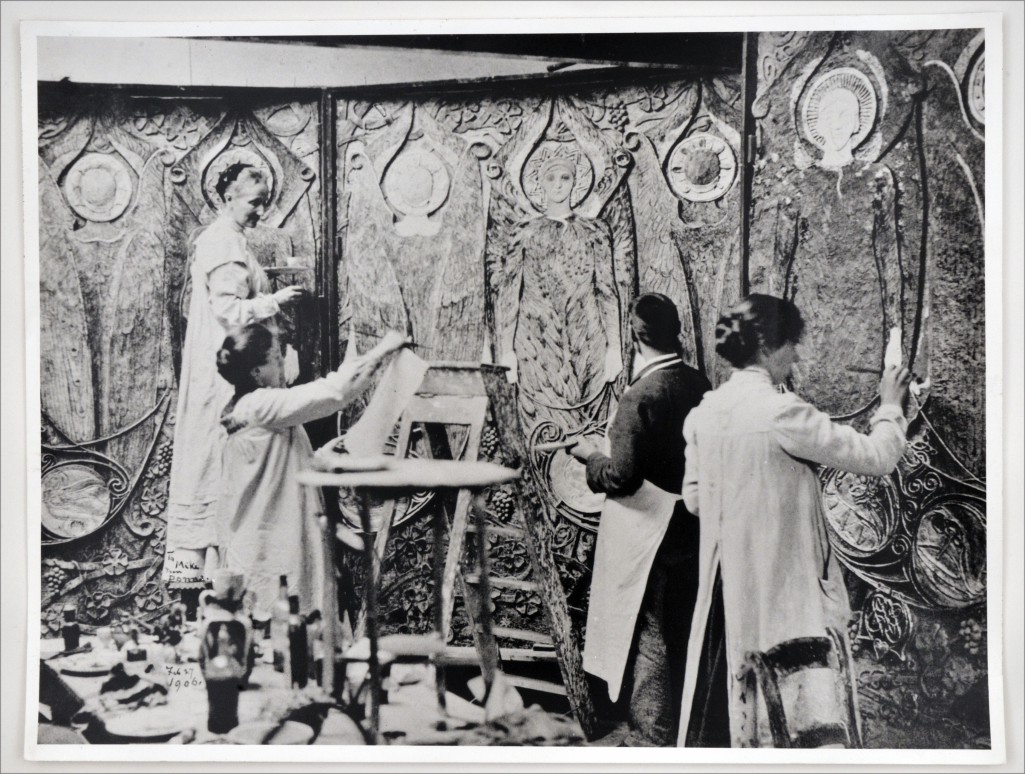

The creation of the Gallery, opened in 1904, was driven by Mary Watts, 32 years Watts’s junior, whom he had married in 1886. A strong interest in the social benefits of art and craft led her to set up classes to teach villagers how to model in terracotta. One result was the extraordinary domed cemetery chapel that she designed and largely decorated herself, with the help of 73 villagers she had trained. Opened in 1898, its symbolic decoration headily fuses the Arts and Crafts movement with the Celtic revival. Still in use, the Watts Chapel is now cared for by the Watts Gallery Trust, which has been granted a 99-year lease as part of its ambition to show and interpret the legacy of what is now branded as Compton, the Artists’ Village.

Another major component is Limnerslease, a half-timbered house designed for the Watt-ses by Ernest George (its tongue-twisting name plays on Old English words for ‘artist’ and ‘harvest’). Completed in 1891, it incorporates a double-height studio for Watts. Sold after Mary’s death in 1938, the house was carved up into three smaller dwellings. In 2011 it unexpectedly came on to the market as a whole and the Trust was able to buy it with a loan from several charitable foundations. With a further grant from the HLF of £2.4 million, the Trust has restored the east end of the house, which contained the studio, and opened it to the public, together with two other small galleries converted from what were always domestic spaces. The work has been carried out by ZMMA, the London-based architects responsible for the restoration of the Gallery.

ZMMA has created a public entrance on the east side of the house, using the same palette of colours and materials as Ernest George – oak, terracotta, and painted timber boarding. Inside, a new oak staircase leads up to a small gallery that introduces the Wattses and their life in Compton. This is followed by a larger space devoted to Mary Watts. Its walls are hung with parts of a scheme of painted gesso reliefs telling the biblical story of the Fiery Furnace, created by Mary between about 1916 and 1920 for the chapel of the Cambridge Military Hospital at Aldershot, and rescued when it closed in the 1990s. Also on show are some of her designs, and volumes of her diaries, which are to be published later this year.

G.F. Watts’s The Court of Death (c. 1879–1902) hangs in the studio above a slot in the floor leading to the room below

Beyond is the studio, recreated on the basis of historic photographs and furnished with canvases by Watts and some of his furniture, including his painter’s table – a tiered palette on a stand. One remarkable feature has been restored. To facilitate working on large paintings, Watts devised a system of pulleys – like those used for painters of theatrical backdrops – whereby canvases could be dropped through a slot in the floor so that he could work on them in the room below.

The next project for Perdita Hunt, the curator Nicholas Tromans, and their team is the restoration of the rest of Limnerslease. Already accessible for small tours, the house will be opened up to the public, providing for the first time since Mary Watts’s death an opportunity for visitors to experience the interconnected lives of the house, studio, Gallery, and chapel: an ensemble without parallel in Britain. Although conceived by Mary as a setting for what she and many others regarded as Watts’s immortal genius, Compton now seems equally compelling as a testament to the creative energy of this remarkable woman.

The Watts Studios opened on 26 January.

From the March issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.