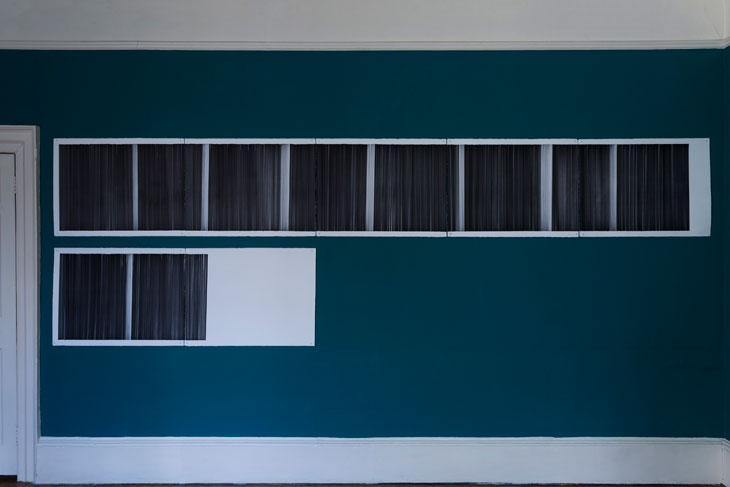

Neville Gabie has made patience his métier. His new show at Danielle Arnaud, a selection from the ongoing project Experiments in Black and White, testifies to that. Take his two Hours of Darkness pieces (2016–17). Standing outdoors from exactly sunset to exactly sunrise, with a ruler and a set of gel pens, Gabie drew smooth vertical strokes on black paper, each one a fraction to the right of the last. The result looks like two tall barcodes, the winter one long and the summer one short. Varying between off-white and a vanishing grey, as each of the pens ran dry, the lines recall not only the dappled night sky, but also the composure of the man who watched.

Hours of Darkness (Stroud) (2016) and Hours of Darkness (Eynhallow) (2017), Neville Gabie. Photograph by Oskar Proctor. Courtesy of the artist and Danielle Arnaud

Gabie, as the exhibition’s curator Tessa Jackson points out, ‘is not by inclination a natural “gallery” artist’. His work often takes place en plein air, and in response to a local setting. (He was the artist-in-residence for the London 2012 Olympics, where he recreated Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières with site-workers, and attempted to sit on all 80,000 of the new stadium’s seats.) But even when his art is born in the disarray of the world, it’s careful to keep itself tidy. For the film Experiments in Black and White XIX (2016), Gabie stands in a Luxembourg quarry, carrying an outsized stack of pristine white plates; wobble, totter, and two minutes later the pile crashes down. He looks aghast, like a true clown should – but the debris is all out of frame.

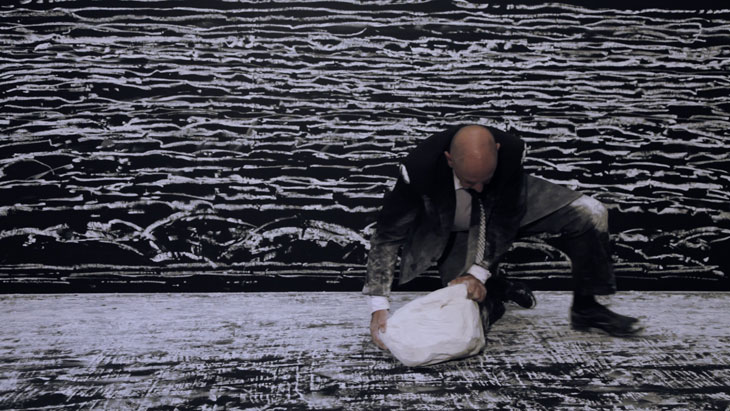

What’s satisfying about Gabie’s work is this discipline, the way it stays controlled. In another film, Experiments in Black and White XXII (2017), he stands against a white background, wearing a black suit, one pot of black paint and one of white at his feet. First he paints himself white, then he turns and paints the background black. Gabie has spent years hearing an obvious take on this work, that it’s a statement on apartheid; he’s a white South African, and keeps as a memento two pieces of limestone from Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned for 18 years. But it’s an angle he finds reductive. To him, this project is about the ‘very human desire to define things in absolute terms’. The conjunction in Black and White is meant to keep those absolutes in constant balance.

Experiments in Black and White VII (video still; 2017), Neville Gabie. Courtesy of the artist and Danielle Arnaud

Gabie’s concern is for distending this balance through time. The Hours of Darkness pieces, he says, are ‘about a very simple repetitive act’ made into a test of ‘endurance’. In a similar vein, downstairs you can stand and watch Experiments in Black and White XXII for a good 64 minutes. By filming his work, not just mounting the result on a wall, Gabie wants to keep you in touch with the ‘physicality’ its creation involved.

During the opening night, the audience saw his efforts in the flesh. Gabie walked over to a giant block of chalk, which had an axe tucked underneath it; he took up the axe, and hewed an edge from the chalk; then he hefted the chalk, moved towards an empty black wall, and began to scrape backwards and forwards from left to right. Twenty minutes later, the wall was criss-crossed with trembling horizontal strips, like one of the Hours of Darkness works on its side. Gabie’s labours were slow and repetitive, and took endurance to watch, but there were unexpected pleasures too. He had to keep putting the outlandish lump down to mop his brow, just as, in Experiments in Black and White XXII, he scooped up white paint to daub his face on realising he’d missed a spot. In these moments, you glimpse something slack, something tender – almost, slipping in, light relief.

‘Experiments in Black and White’ is at Danielle Arnaud, London, until 17 February.