Antony Griffiths presented this study of early modern prints as the Slade Lectures at Oxford in 2015. Eight lectures have grown into a very large text. The sheer amount of information on offer here, conveyed in such a lucidly written and lavishly illustrated book, marks this as a pinnacle of print studies. As former Keeper of the Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, Griffiths draws on the museum’s collection, which provides all of the over 300 illustrations in this volume. But one hopes that this magisterial study is not Griffiths’ last book on the print in Europe. As he says, the history of prints is in its infancy, and one hopes that he will continue to elevate the level of writing on this crucial subject.

For this book is not a history of prints in general, nor of early modern prints in particular. Griffiths calls it a reference book: it is not narrative in its organisation, but thematic. Thirty-one chapters, some brief and others lengthy, treat topics from the technology of printmaking and its implications, to the print publisher and the financing of print production, patronage, censorship, the survival and loss of prints, and print-collecting, among others. Figures such as the sophisticated and well-connected print publisher François Langlois, called ‘Il Chiartres’ for his birthplace (here seen in a print after a painting by his friend Anthony van Dyck) emerge from this densely reconstructed context in a new, sharp relief.

Portrait of François Langlois, called ‘Il Chiartres’ (c. 1650), Jean Pesne after Anthony van Dyck. British Museum, London; Courtesy The Trustees of the British Museum

The title, The Print Before Photography, signals the distinctive approach taken to the subject. The advent of the photograph in the 19th century provides the end date for Griffiths’ study, as photography ‘and the processes that depend on it have made [print technologies] obsolete, and the twentieth century steadily removed the pre-photographic print from everyday view’. What photography eventually destroyed was not just a market for handmade imagery, but a set of assumptions about representation; however, that issue is not Griffiths’ concern. It is the distinctive processes by which prints were made, authorised by the state, sold, and distributed that Griffiths defines here, in an attempt to ‘resurrect this past world, its conventions and assumptions, and the technical constraints that underlay the production’. The focus of the first half of the book is the print trade, and in this area Griffiths brings together an enormous amount of material into a clear, readable synthesis, something that has never been available before. The author’s aim goes beyond this in the second half, illuminating an entire system of image production and usage, which was formed in the 16th century and vanished by the middle of the 19th.

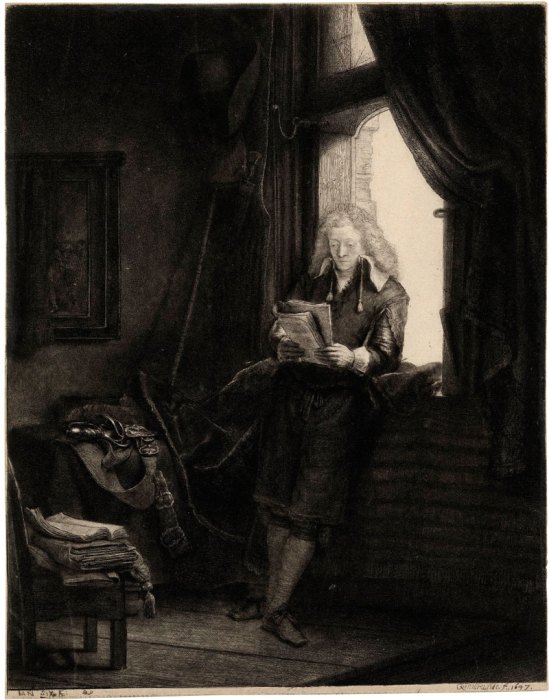

It is as a monolithic system, a ‘unity’, that the author depicts this lost world. Seventeenth- and 18th-century sources contribute to the discussion of each topic; changes within this period or variations between different geographical areas are downplayed. This approach separates The Print Before Photography from its predecessor, another fundamental text on European prints, The Renaissance Print 1470–1550 by David Landau and Peter W. Parshall. Landau and Parshall present a chronological narrative moving back and forth between Italy and northern Europe, with a focus on artists’ careers. One can see why Griffiths, in handling the later period, would find it necessary to abandon this more art-historical format. Prints were internationally traded by the 17th century, and printmakers and publishers moved from country to country with ease. In the commerce of prints, the artist-printmaker was only one small player, among many others who often had greater investment in print production. The ‘art print’ was only one small category within the huge numbers of printed sheets in circulation. The artificial scarcity of some Rembrandt prints played against this market, as when impressions of his portrait of Burgomaster Six, whose family retained the plate, reached astronomical prices.

Portrait of Jan Six (1647), Rembrandt van Rijn. British Museum, London; Courtesy The Trusees of the British Museum

Griffiths studies the entire spectrum of subject matter and levels of artistry available to the early modern buyer of prints, from high to low and even the category of ‘demi-fine’ or middle market. If, like me, you are interested in ‘cheap prints’, which Griffiths rightly defines by their cost rather than their supposedly ‘popular’ audience, this study helpfully integrates them into the broader business of prints. Unexpected uses of printed images crop up: a life-size etching of a rabbit surviving in only one impression in the British Museum was probably created as a target for shooting practice. A skull and crossbones print served as a sign placed on doors to warn of the plague’s outbreak within. At the other end of the spectrum, the practices of printmakers such as Jacques Callot in making copies or replicas of their own images are illuminated here. As too is the role of prints in the early modern artist’s studio and the various relationships between painters, sculptors, and printmakers.

A Rabbit seen in profile (c. 1560–90), artist unknown, Netherlandish. British Museum, London; Courtesy The Trustees of the British Museum

The Print before Photography has riches to offer any reader, in any field and at any level of study of European prints. If, on the one hand, Griffiths gently rebukes art historians who want to see all prints as either successful or failed works of art, he also takes historians to task for their reductive approach to pre-modern prints – as if they were documentary photographs of events or people. While one might miss here the sustained attention to the visual effects of prints, which Griffiths has provided in other works, that is a price worth paying for this book’s encyclopaedic knowledge. If one wishes to learn more about the role of the print business in specific localities during this period and how it interacted with other areas of cultural production (I am thinking of France at the end of the 17th century, or Italy at the end of the 18th), that can wait for a different history of European prints. On the basis of this important volume, we must hope that Antony Griffiths will go on to provide it.

The Print Before Photography: An Introduction to European Printmaking 1550–1820, by Antony Griffiths, is published by British Museum Press.

This book is shortlisted for the Apollo Book of the Year Award 2016. View all the shortlists here.

From the November issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.