By the time Nicholas Serota starts his new job as chairman of Arts Council England next February, he will doubtless have read The Arts Dividend, the latest book by his Chief Executive, Darren Henley. Serota does his homework. Henley, appointed by the outgoing chairman, Peter Bazalgette, has been in post since 2015, and The Arts Dividend is presented as an account of his travels through cultural England during his first year.

Henley, who previously served for 15 years as head of Classic FM, has more than 30 books to his name, but his most influential publications have been the independent reports he wrote for the government in 2011 and 2012 on music education and cultural education. He seems to have the ear of the Department for Culture, and although The Arts Dividend is not an official Arts Council publication, it clearly hopes to bend that ear once more. Hence his subtitle: ‘Why investment in culture pays’.

Although the implication is clear, Henley holds up his hands in horror at the thought that the arts need money. He ‘cannot abide’ the term subsidy. What the Arts Council does is invest. It is remarkable how little the arguments to justify that ‘investment’ have changed since the Arts Council of Great Britain received its royal charter in 1946. Henley almost immediately cites its first chairman, John Maynard Keynes, though he does admit to the ‘lofty separation’ between artist and the general population in those days.

This being a politically motivated publication, Henley also cites George Osborne’s remark that ‘£1 billion a year in grants adds a quarter of a trillion pounds to our economy – not a bad return.’ But a year is a long time in cultural politics, and Osborne, like John Whittingdale, also carefully cited, has left the scene. Henley and Serota have to create a whole new set of relationships.

Henley presents the case for arts investment in terms of seven ‘dividends’ that, for all their fancy titles, add up to saying the arts are A Good Thing. Only the ‘Feel-Good Dividend’ brings something new to the argument. He cites evidence that the arts really do (as Aristotle said) have therapeutic benefits, and can indeed be prescribed. A ‘league table of happiness’ puts theatre, dance and concerts at the top, reading at the bottom. The Treasury has been taking an interest in measuring the cost-effectiveness of wellbeing, but it is doubtful that we will be able accurately to gauge the medicinal benefits of truth, beauty, or a sense of the sublime.

For all of his claims for the intrinsic value of the arts, Henley relies on the instrumental benefits that result: the economic value of the creative industries, the regenerative benefits to towns and cities, international tourism. There is nothing exceptionable about this, any more than are the things he argues for more of: diversity, creativity, cultural education, university participation and a rebalancing of funding away from London towards the other regions.

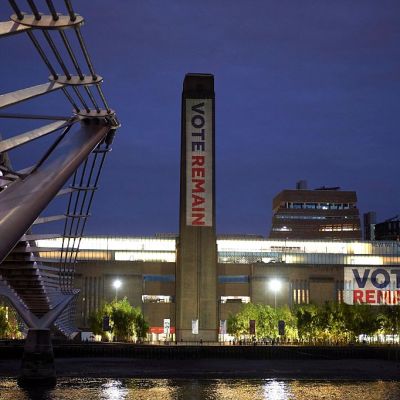

Yet Henley and Serota face a much more challenging agenda than this. Henley acknowledges that local authority funding ‘is tight’ – a politic under-statement if ever there was one – and that libraries are in trouble. But nowhere does he acknowledge that participation in the arts has been flatlining for a decade. The government’s Taking Part survey shows that those who really benefit from the arts dividend – that is, those who take part more than once or twice a year – are a minority, and an educationally and socially privileged one at that. The recent referendum shows what a gap there is between those who have access to and enjoy the arts, and a larger group, in all classes, who seem resentful.

There is no doubt that Serota’s appointment is a good one. He has the trust of artists, the respect of politicians, and great personal skills. But he faces the same challenge as all previous chairs: how to promote the best that has been thought and said (and what has not been said before), without creating a lofty separation between those who already buy Henley’s arguments, and the alienated many who are not interested. To square the circle between those dead terms, access and excellence, really would be a dividend.

The Arts Dividend, by Darren Henley, is published by Elliott & Thompson Limited.