‘Nature found and struck wonderfully well with her man […] when she went to pick him out in Brabant, in an obscure village, among peasants.’ That is how Karel van Mander, the Vasari of the Netherlands, opened the brief life of Pieter Bruegel in his Schilderboek (1604). The painter was, for van Mander, a humble farmer’s son who rose to a position of eminence, but never cut himself off from the world that made him. Later in life, van Mander records, the one-time peasant would don village costume once more and head out of Antwerp with his friend Hans Franckert to crash peasant wedding parties. Blending in, they gave gifts like anyone else, told anyone who asked that they were family or friends of the happy couple, and spent their time observing the peasants ‘in eating, drinking, dancing, leaping, lovemaking’. Then, van Mander implies, Bruegel returned to his workshop and set them all down in ink and paint.

By the gauge of some of Bruegel’s most famous works, van Mander’s account is a perfect fit. The closely watched peasants are there still in Peasant Dance (c. 1568) and The Peasant Wedding (c. 1567), doing all those things, in every mood, in every state of sobriety, and at every stage of life. In the five surviving paintings of the Months (1565) and the two finished drawings of the Seasons (1565, 1568), they do more besides, at every stage of the calendar. If further evidence of close observation were needed, one drawing survives of what must have been a whole series of peasant figure studies: a bagpipe player on his stool, cheeks puffed, seat tilting under the pressure of his tune. If it is unlikely, in so finished a state, to be a study from life, it is nevertheless full of life. The average Bruegel peasant is cheerfully stolid but no less animated: lovingly observed but rarely flattered, he passes through the world with a spoon stuck in his cap, forever on the way to the next meal and the next drink.

Doubtless, this is a romantic view of peasants and painter both, but it is hard to deny its charm. Van Mander’s Bruegel strides out towards the reader like the central subject of his own late masterpiece The Birdnester (1568). Nicknamed ‘Pier den Drol’ – ‘Funny Peter’ – he is a humble fellow, a twinkle in his eye, a smile on his face, and one finger forever forgivingly cocked at the folly of the world.

The truth, though, is less open faced. For all the temptation that the figure who emerges from the Schilderboek biography – natural genius, comedian, ethnographer – exerts, the fact is that we know little about the life behind the works that remain to us. Writing some 45 years after Bruegel’s death, van Mander may have had access to people who knew the painter – Bruegel’s own mother-in-law, for instance, outlived him by 30 years – but there is no guarantee of his reliability. Not least because of his concern to memorialise the artists of the Low Countries and Germany just as Vasari had the artists of Italy, van Mander’s anecdotes tend toward the flattering and formulaic. And the peasant Bruegel he describes is in no small part a posthumous artefact, amplified by market demand for the dead artist’s village scenes, and the innumerable copies of them painted to cash in on it. With no fewer than 127 known versions of Winter Landscape with a Bird Trap (1565) alone circulating in the 17th century – some 50 of them emanating from the workshop of Pieter Brueghel the Younger – it is little wonder that van Mander should think of Bruegel as a documenter of village life, and that he recount the stories that fit that image best. When it comes to his Bruegel vignettes, it is hard to say which have the ring of truth, and which the ring of too much truth.

In the run up to the 450th anniversary of Bruegel’s death on 9 September 2019, however, two projects are prompting and aiding reconsideration of the artist and his work: a commemorative exhibition assembling three-quarters of the extant paintings at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna (2 October–13 January 2019), and the publication this month by Taschen of a sumptuous Complete Works. Put together with what we do know about the artist himself, the surviving body of work – some 40 or so paintings, 60 drawings, and 80 prints, the latter in large part overlapping with the drawings – limns a considerably more nuanced portrait of Bruegel.

Before the earliest known works, we know with certainty astoundingly little – nothing at all, in fact, about the first 25 or 30 years of Bruegel’s life. He may have been born, as van Mander states, in the village of Bruegel in what is now North Brabant, but there is more than one village named Bruegel or Brogel, and van Mander offers no year of birth. We do know, thanks to a monument erected (some years after the fact) by his son Jan, in Notre-Dame de la Chapelle in Brussels, that Bruegel died there in 1569. The first time that a ‘Peeter Bruegel’ surfaces in an appropriate document before then is in a 1551 record of admission to the Antwerp artists’ guild, the Guild of St Luke. If this is Bruegel himself – of which there is no guarantee – he would have most likely entered the guild between the ages of 20 and 25, putting the year of his birth somewhere between 1525–30.

The earliest concrete evidence of Bruegel as an artist comes from the records of an altarpiece commissioned by the Mechelen glovers’ guild. Though the painting is now lost, it places Bruegel in Mechelen in 1550 and 1551, where he worked on the triptych’s grisaille outer wings. The dating accords neatly with van Mander’s statement that Bruegel’s early training was with Pieter Coecke van Aelst – one of the Netherlands’ foremost painters and tapestry designers – who died in 1550. His master’s death would, it is easy to imagine, have spurred Bruegel to seek work on his own account, and may be linked to the timing of the admission document to the Guild of St Luke.

If Bruegel did train with Coecke, there is little trace of it in his work. Coecke worked in a strongly Italianate style – influenced by training in Rome, or at the least through familiarity with the Raphael cartoons being used in the tapestry workshops of Brussels. Neither the figural luxuriance typical of Coecke’s religious works, like the Prado’s Triptych with the Annunciation, the Adoration of the Magi, and the Nativity with Angels and Shepherds (c. 1525–50), nor the flattened, tableau-like quality of his tapestries, like the Story of Abraham series (1540–43) at Hampton Court, is visible in the throngs and landscapes of Bruegel’s work. If any influence can be traced, it seems less likely to be from Coecke himself than from his wife Mayken Verhulst. Though no firmly attributable work by her survives, she was a miniaturist and watercolourist of note – a proponent of the pictorial tradition that most visibly informs Bruegel’s work. Her link to Bruegel himself is, too, firmer than Coecke’s: after Bruegel’s marriage to her daughter, Mayken Coecke, in 1563, she takes up the role of long-lived mother-in-law; and, according to van Mander’s biographies of the next generation of Bruegels, served as the first teacher of Pieter the Younger (1564/65–c. 1638) and Jan (1568–1625).

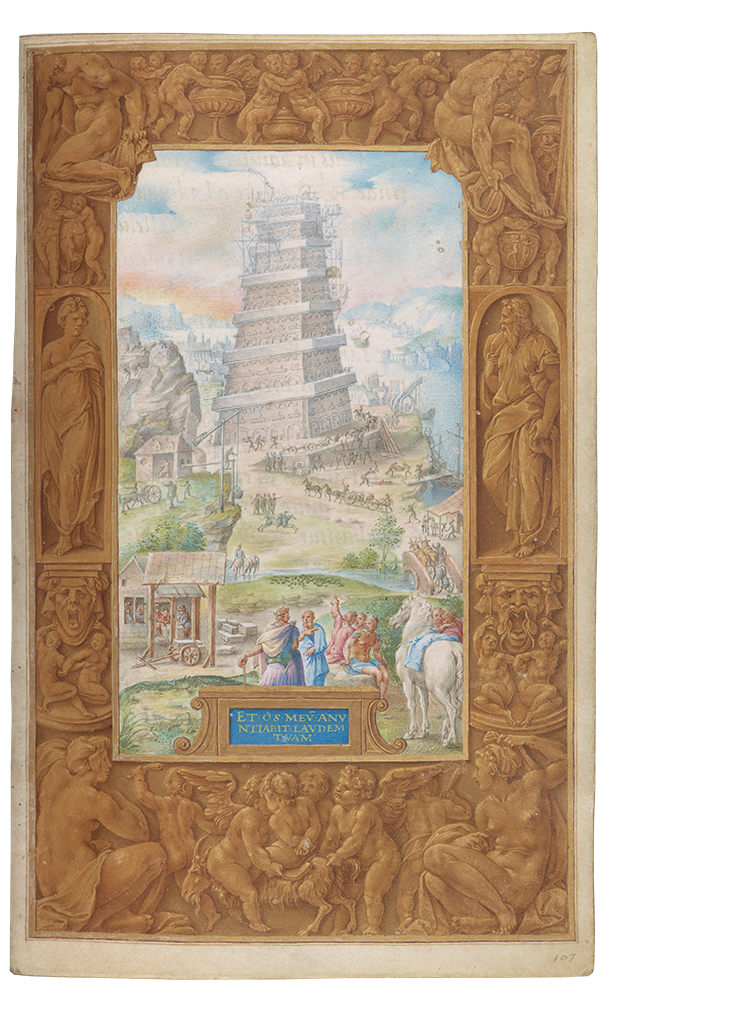

After his work in 1551 on the Mechelen altarpiece, Bruegel slowly emerges into the light through documents and, much more substantially, his own works. Several drawings – among them the View of the Ripa Grande (c. 1555/56) – confirm van Mander’s account of a trip to Rome. There he appears to have met and collaborated with the Croatian miniaturist Giulio Clovio (Julije Klović), perhaps the most important miniaturist and illuminator in Italy at the time. Though we have no way of knowing how close the men were, a 1578 inventory of Clovio’s estate records his possession of a miniature ‘half by his own hand, half by Maestro Pietro Brugole’, and, by Bruegel alone, a gouache view of Lyons, and a Tower of Babel on ivory. None, unfortunately, survive.

The mention of the latter is particularly tantalising given the looming presence of the Tower in Bruegel’s later paintings. One of Clovio’s own treatments of it can be seen, though, in the Morgan Library’s Farnese Hours (1546) – completed a few years before the men met. Despite the disparity in size, it is strikingly similar to both of Bruegel’s surviving treatments, from the same spiral construction of Roman arches, to the sweep of sea to the right-hand side of its base, complete with ships unloading stone. It is easy to imagine how an exchange of ideas might have taken place.

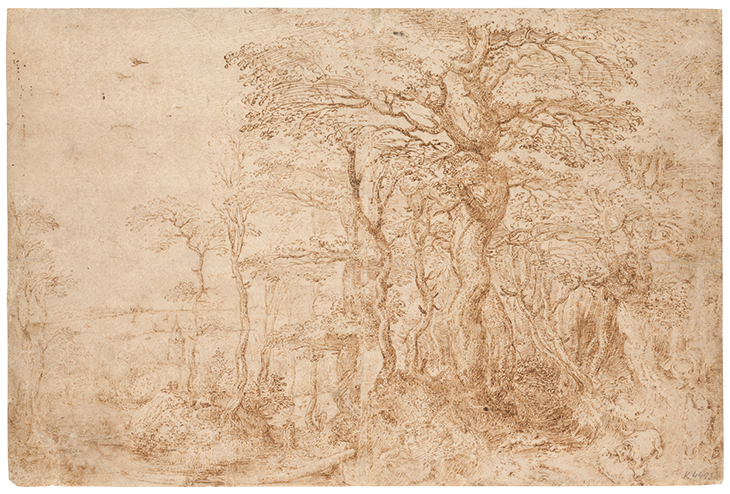

However little we will ever know about it beyond a teasing entry in an inventory, friendship with Clovio complicates the familiar old account of ‘peasant Bruegel’. Clovio’s place in the Roman art world at the time is amply summed up by his presence in the lower right corner of El Greco’s Christ Driving the Money Changers from the Temple (c. 1570), now in Minneapolis. There he looks out at the viewer alongside Titian, Michelangelo, and Raphael. It is, perhaps, a testament to the enduring image of the provincial boy made good that we find it hard to imagine Bruegel in the same company. And yet critics have long identified the influence of Titian in the Alpine landscapes and other nature studies – such as the singularly lush Sylvan Landscape with Five Bears (1554) – that Bruegel executed during and after his Roman stay.

Despite the lack of direct evidence about who and what he saw in Rome, it is worth remembering – as Katrien Lichtert has recently noted – that such artistic pilgrimages by northern European artists were undertaken precisely, in Vasari’s formula, per apprendere la maniera italiana.

From 1554, Bruegel is to be found in Antwerp, embarking on his career in earnest. Except it is not the career that is familiar to most viewers of his work. Though his output over the next few years was vast, it appears to have been almost entirely restricted to drawings and designs for prints issued by the prolific Hieronymus Cock, and destined for the flourishing international print market. It is, however, in these commercial pieces that the seeds of the later works for collectors and connoisseurs are sown. And seen in the light of his work for Cock, the paintings upon which Bruegel’s reputation largely rests today take on a different light.

A crucial element is the adaptability – of works and artist alike – that was necessary for success on the early modern print market. It says much about the generic malleability of Bruegel’s work that the first print Cock etched from his work transformed Sylvan Landscape with Five Bears into The Temptation of Christ (c. 1554). While the rest of the landscape is minutely transposed, the five bears that tumble and play in the drawing have been replaced with Christ and Satan. Despite its exaggerated incongruity, the swap is a version of something seen throughout Bruegel’s later work. Here, as in many landscape prints that followed over the next few years, Bruegel slips into his particular tactic – so memorably evoked by W.H. Auden’s ‘Musée des Beaux Arts’ – of confining his supposed subject to some out-of-the-way corner of the work. In the prints that followed the Temptation the technique is repeated time and again: St Jerome and his lion miniscule by a tree stump, while a magnificent vista unfolds to their left; the penitent Magdalene under a bivouac of pine branches, while a river wends its way through a valley towards a distant town; Jesus and two disciples, backs turned, all equally unidentifiable in travellers’ cloaks and hats, their journey on the Road to Emmaus insignificant against that of the long river working its way to a distant sunset.

The same manoeuvre – or habit, perhaps – runs throughout Bruegel’s later religious paintings. Though often heavily populated, unlike the landscape prints, their ‘subjects’ tend to take place in some minor and pictorially inconspicuous position, with the viewer’s attention drawn off somewhere into a distant view, or into a multitude of happenstance goings-on, or both simultaneously. The Courtauld’s small Landscape with the Flight into Egypt (1563) devotes only the tiniest fraction of itself to the Holy Family, with the baby Jesus snuggled in Mary’s cloak taking up no more space than the perched magpie they have just ridden past. In the following year’s Christ Carrying the Cross – Bruegel’s largest known panel painting – Mary and Saint John are foregrounded, but Christ himself almost disappears in the sea of figures around him. And so too, astonishingly, does his punishment: Bruegel’s Calvary is an all-purpose spot of chastisement, dotted with breaking-wheels and gallows, where something approaching a carnival atmosphere reigns, and children are piggybacked up the hill to watch. It is the ‘Hill of the Skull’, certainly, but in Bruegel’s version, the skull – prominently displayed on a heap of earth in the bottom right – belongs to a horse. This is a technique that, while giving the appearance of ‘natural’ artistry, as van Mander would have it, in fact owes everything to Bruegel’s technical skills in working across media, and his commercial eye for catering to several markets simultaneously – combining devotional art, landscape, and genre scenes in a single pictorial space, and a single product.

In 1554, however, the grandest paintings were still some way off. Indeed, few of Bruegel’s paintings date from before 1562 – Parable of the Sower (1557), Netherlandish Proverbs (1559), The Battle Between Carnival and Lent (1559), and Children’s Games (1560) are among them – and all of them are rustic or peasant scenes. It is unclear whether, like the Mechelen altarpiece wings, there were further earlier paintings that do not survive, or whether Bruegel was simply busy with other projects. There is, however, a clear continuity between the more than 40 drawings for prints, largely issued by Cock and his engravers, that Bruegel made between 1554 and 1562. And though viewers tend to be drawn to the paintings above all else, these early designs are a central part of his oeuvre, and vital evidence for the complex and contradictory artist he was. As with the religious landscapes, there is the sense in almost all the prints – catering to consumers across the continent – of compositional techniques and preoccupations being laid down for later work.

Among the most striking of these are the Boschian fantasias of the Seven Deadly Sins series (1556–58), produced to cash in on the pan-European market for Hieronymus Bosch’s work – prints that laid the foundation for the large-scale Boschian homages of The Triumph of Death (1562/63), The Fall of the Rebel Angels (1562), and Dulle Griet (1563). It is for prints like these, issued long before the paintings, that Bruegel earned the nickname ‘Second Hieronymus’, but they also put him on the path to work that is entirely his own.

Shortly after them come the individual masterpieces of satire that turn an unforgiving eye on man’s folly and blindness without recourse to collaged imaginings of another world: The Alchemist (c. 1558) and Everyman (c. 1558). In the former, the eponymous seeker spends everything he has on fruitless experiments until his family starves and has to go begging, all while a faithful amanuensis presides over a book that reads ‘Alghe mist’, punningly ‘alchemist’ and ‘already missed’ or ‘all wasted’. In Everyman, meanwhile, a series of identical figures search myopically through the heap of wreckage that is the world looking for trinkets, casting their lantern light into everything but self-knowledge, and ignoring the army gathering in the distance. These look forward to the strange late paintings The Misanthrope and The Blind Leading the Blind (both 1568): dispatches from a world where people are incapable of seeing the traps and dangers that lie all around them.

Perhaps the most striking print designs that Bruegel accomplished, though, are those of The Seven Virtues (1559–60). Though a partner set to the Deadly Sins, they move beyond recycled motifs and into something wholly Bruegel’s own, casting an unforgiving eye on his own world. They illustrate for the viewer what that world must be like, at base, to require of us so much faith, hope, charity, justice, prudence, temperance and fortitude. At the centre of each drawing stands the personification of the virtue, blithely unaware – it seems – of the deficits that make them necessary. Faith, in the middle of a crowded church, stands upon an open tomb; Hope on the anchor of a sinking ship in a scene where, as some drown, others burn, and others again die of thirst jailed in a tower, dangling a jug through the grille in the vague hope of catching some rain. But it is Justice who strikes the darkest note: blind, the virtue stands with her sword and scales in a landscape devoted entirely to punishment. With hangings, beheadings, men being broken on wheels, a thief having a hand chopped off, and more besides, it is hardly a vision that makes the human version of justice seem like much of a virtue. The same world provides the background to Christ Carrying the Cross and the painting that may have been Bruegel’s last, The Magpie on the Gallows (1568): a world in which we are all forever under the shadow of punishment for reasons we are ill equipped to understand.

To look at Bruegel’s print designs closely is to see all the paintings that come after them – light and dark alike. In the next decade, against the backdrop of the unholy viciousness of the Low Countries’ religious conflicts, he would marry, have two sons, and become one of the most sought-after painters of his time. Four successful years after Bruegel moved to Brussels in 1563, the Duke of Alba commenced a reign of terror that represented the culmination of the oppression and censorship that had long been the norm in the region. Life went on, but so, very much, did death. It is entirely easy to see, against such a background, how the peasants dancing at a wedding might seem, for artist and viewer alike, a worthy subject to cling to. But it is also easy to understand how the open-faced fellow pointing his finger at the carelessness of the birdnester might have a more serious kind of joke on his mind.

‘Bruegel’ is at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, until 13 January 2019.

From the October 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.