What lends the Greek epic poem The Odyssey its enduring appeal is not just the tales of sirens and wiley gods. Rather, at the heart of the narrative lies the hero’s protracted homecoming, even after he has returned to Ithaca after 10 hard years away. Disguised as a beggar in his own court, Odysseus outwits and kills the suitors to his wife, Penelope, who have tried to usurp him in his absence.

In some ways, the Athens branch of the 14th edition of Documenta is meant to signal a similar return voyage, this one back to the troubled origin of European art and civilisation. For the first time, the quinquennial fair is being held in two locations – in Kassel, Germany, its usual home, and in the Greek capital, under the theme ‘Learning from Athens’. In one fitting performance – Pope.L’s Whispering Campaign – volunteers play whispered fragments of Greek myths and songs in some of Athens’ public spaces. Like Odysseus reasserting himself in his own kingdom in disguise, Documenta aims to make Athens felt, not just seen.

Whispering Campaign (2016–17), Pope.L. Photo © Freddie Faulkenberry

Adam Szymczyk, Documenta’s artistic director, has suggested in interviews that Athens was selected to shed light on the power dynamics of a crumbling Europe. The programme draws attention to pressing issues of migration, citizenship and identity, foregrounding the work of dissident or disenfranchised artists. Former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis has condemned the event as ‘crisis tourism’, and one would have to be blind not to notice the angry ‘Crapumenta’ graffiti on the walls of the city. There is a painful irony in the fact that the Athens show is funded by Germany, and critics have rightly questioned whether Documenta can meaningfully address, as it claims to, the ‘palpable tension between the North and the South as it is reflected, articulated, and interpreted in contemporary cultural production’ when so much contemporary art seems to prop up an increasingly homogenised clobal culture. What the event does do, however, is draw attention to the under-recognised gems of Athens, albeit in ways it probably did not intend.

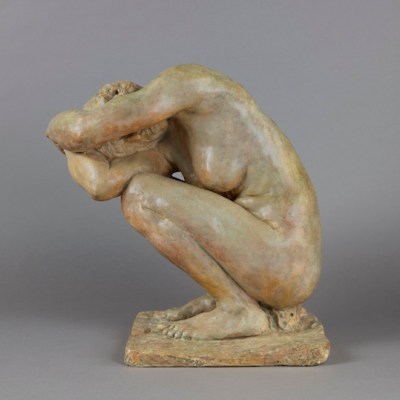

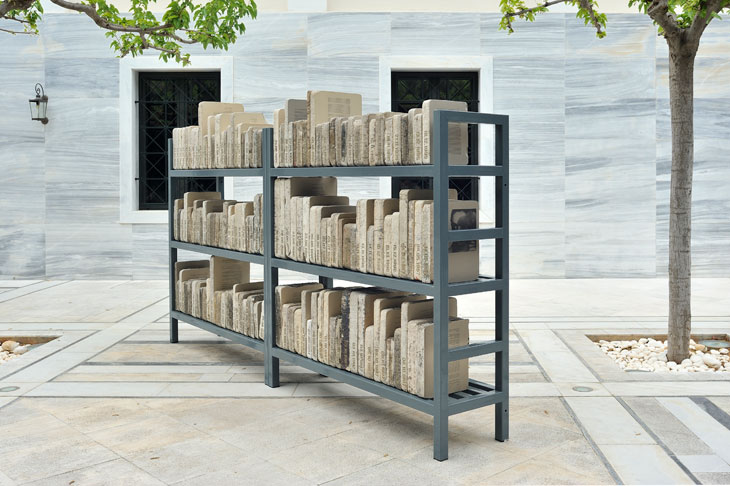

The Gennadius Library, which is located on the leafy slopes of Mount Lycabettus and boasts an impressive collection of more than 100,000 volumes on history, literature and art from ancient Greece to modern times, is home to one of the most thoughtfully curated spaces at Documenta. In the courtyard of the museum, visitors are greeted by what appears to be a shelf of books made from stone. This is Banu Cennetoğlu’s multimedia installation Gurbet’s Diary (27.07.1995 – 08.10.1997). It comprises 145 lithographic limestone slabs engraved with the Greek translation of diary entries by Gurbetelli Ersöz, a chemist-turned-editor of a pro-Kurdish newspaper who was tortured and eventually killed for her political activism. ‘Manuscripts don’t burn’, Mikhail Bulgakov famously wrote in his classic novel The Master and Margarita. What bittersweet truth there is in those words, as Ersöz’s life is made monumental through Cennetoğlu’s work.

Gurbet’s Diary (27.07.1995–08.10.1997) (2016–17), Banu Cennetoğlu. Photo: © Freddie Faulkenberry

The interior of the library hosts the project Learning from Timbuktu. Curator Igo Diarra, who is the founder and director of the art space La Medina in Bamako, has brought together several artists who have focused on raising awareness about the richness of Malian heritage. Seydou Camara’s photographs of the manuscripts of the historic Ahmed Baba library in Timbuktu, which were endangered during the 10-month occupation of the city by Tuareg separatist rebels, are especially poignant. Hanging from the banisters of the second floor, juxtaposed against the neatly preserved collection of the Gennadius Library, they seem to be making a silent cry to not be forgotten. This is one of the locations in which the orchestration of marginalised voices is most clearly articulated; elsewhere at Documenta things are a lot more chaotic.

At the Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), founded in 1871 by the Athens Music and Drama Society, sound and music are quite literally the instruments through which resistance – in this case to materialism – is explored. Nevin Aladağ’s Music Room (Athens) transforms furniture and other inanimate objects into evocative instruments, challenging us to rethink our utilitarian view of the world around us. The human body has become accustomed to the set routines that these objects were built for; Aladağ’s installation/performance is a clever exercise in unlearning these habits.

In this shared complex, other artists have opted for more direct critiques. Iraqi artist Hiwa K’s video Pre-Image (Blind as the Mother Tongue) takes us with him through fields, temples and shipyards as he stumbles about with a mirrored stick on his nose, retracing his journey from Turkey to Athens when he was forced to flee his homeland. In one scene, the screen remains black for almost 20 seconds as he recounts the experience of smuggling himself across the continent in a shipping container with only a slice of cake for food, not knowing when or whether he would reach land. The mirrored stick has a disorientating effect, offering us a vision of a fragmented world.

Pre-Image (Blind as the Mother Tongue) (2017), Hiwa K. Photo: © Mathias Völzke

Emeka Ogboh’s multichannel sound installation The Way Earthly Things Are Going (2017) is a ghostly aural landscape of Greek choruses, accompanied by an LED board flashing global stock indexes. Most haunting of all is Susan Hiller’s The Last Silent Movie, an audio compilation of disappearing and extinct languages recorded by their last surviving speakers, including the Xokleng from Santa Catarina in Brazil, and a whistled language from the Canary Islands. In one emotionally charged, unsubtitled segment punctuated by static, an older woman’s voice quietly sings a lullaby in the South African Kulkhassi language. No translation of the song exists because there is no one left to translate it. These works summon the ghosts of things we have lost without even realising it.

Not every space at Documenta is so carefully curated. The sight of Rebecca Belmore’s marble tent near the top of Filopappou Hill, for example, is quite puzzling. It is meant to symbolise the refugee crisis in Greece, but situated this far away from the pulse of the city, its message falls somewhat flat. Parko Eleftherias, home of the Museum of Anti-dictatorial and Democratic Resistance, houses various works including a site-specific installation by Andreas Angelidakis. But one is left wondering whether visitors would benefit more from an introduction to the tragic history of the building itself, which was used as a detention and torture facility during the military junta of 1967 to 1974.

Biinjiya’iing Onji (2017), Rebecca Belmore. © Fanis Vlastaras

Documenta’s largest venue in Athens, the EMST National Museum of Contemporary Art, includes works by a range of luminaries including the deceased Forough Farrokhzad, who is represented by her acclaimed short film, The House is Black, about Iranians afflicted with leprosy. Despite the quality of the art shown here, the display as a whole comes across as overcrowded and un-coordinated. It’s not clear, for example, what – if any – link is being made between the highly emotive The House is Black and the abstract paintings that dominate the following room.

But to be at Documenta is to be out and about in the city, and it is this that really allows us to learn from Athens. Any discussion about statelessness, borders and geopolitical instability is meaningless without direct action. One may be lured to Athens by the promise of art, but if Documenta’s gesture is worth anything at all, it is to encourage conversation among people beyond the art world’s confines. To speak to ordinary Athenians about their lives and their remarkable defiance in harsh times in between one’s exploration of the show is to gain a better grasp of where Athens is in the world: it is a place marked by anger, but also a deep, unassailable pride.

An event like Documenta is not necessary for such dialogues to take place. But equally, we ought to seize every chance at genuine cultural exchange when it arises.

Documenta 14 ‘Learning from Athens’ runs at venues throughout the city until 16 July 2017.