Dismembered limbs and warped torsos, breasts in pudding glasses and crooked stumps of sticky resin resembling mutilated entrails: the work of Alina Szapocznikow can be an unnerving prospect. For visitors to the retrospective exhibition ‘Human Landscapes’ at the Hepworth Wakefield, it is also likely to be a new one.

Although Szapocznikow remains well known in her native Poland, after her premature death in 1973 she all but vanished from international galleries. This has been slowly rectified over the past decade through the efforts of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, which has archived her work and collaborated on exhibitions in major international institutions including MoMA, WIELS and the Centre Pompidou. ‘Human Landscapes’ is her first significant exhibition in Britain. It is also likely to be last. Many of Szapocznikow’s works, such as her early 1960s plaster and found object sculptures, are exceptionally fragile. During the latter half of her career she experimented with industrial materials including polyester resin and polyurethane, which have a tendency to degrade rapidly.

Installation view of ‘Alina Szapocznikow: Human Landscapes’ at the Hepworth Wakefield. Photo: Lewis Ronald. Courtesy the Hepworth Wakefield

Atrophy has a distinct place in Szapocznikow’s art, which consistently foregrounds the frailty and mutability of the human frame. She had ample reason to be aware of such processes. The child of non-practicing Jews, she was confined to the ghetto in 1940 and two years later sent via Auschwitz to Bergen-Belsen and Theresienstadt. After her release she studied art in Prague then Paris, where in 1950 she contracted tuberculosis and was spared by an experimental treatment. Szapocznikow never spoke of these traumas, but their spectres glower behind much of her practice.

In the first decade of her career, she explicitly addressed the ravages of the 20th century. Upon returning to Warsaw in 1951, she began to sculpt in the state-mandated Socialist realist style, which she quickly transcended. The bronze nude Difficult Age (1956), for instance, has some of the sinuous authority of Rodin. It was with Exhumed (1955), a sepulchral depiction of the executed Hungarian politician László Rajk, that Szapocznikow began mutating the body of her subjects. Rajk looks like a crumbling remnant of an ancient civilisation, his limbs stunted, his face caved in. Her drawings of this time, in crayon, ink and ballpoint as well as pencil, show her transfiguring human forms into globular, fleshly lumps.

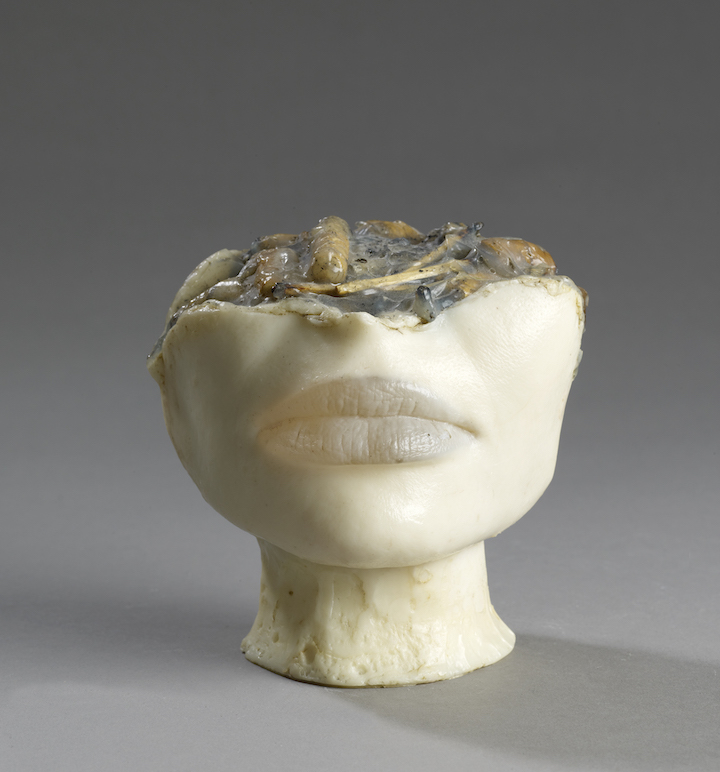

The Bachelor’s Ashtray I (1972), Alina Szapocznikow. © ADAGP, Paris 2017. Courtesy The Estate of Alina Szapocznikow / Piotr Stanislawski / Galerie Loevenbruck, Paris. Photo: Fabrice Gousset

Leg (1962), a gnomic plaster cast of her own limb, was something of a turning point. From this point on, Szapocznikow began to experiment more widely with materials and techniques. Moving to Paris in 1963, she first echoed the nouvelle réalistes in incorporating found objects into her work, from bike wheels to Nazi weaponry. But it was when she discovered plastics that she developed her mature voice. With pieces such as the Lamps (1966–67) – functioning electric lights with luminous polyester lips and breasts as their shade – the intersection of eroticism and capitalism became her second great theme. The Bachelor’s Astray (1972), which catches cigarette ends in the bottom half of a female bust, presents an uncomfortable combination of human form and commodity object.

Self-portrait – Herbarium (1971), Alina Szapocznikow. Grazyna Kulczyk Collection. Courtesy The Estate of Alina Szapocznikow / Piotr Stanislawski / Galerie Loevenbruck, Paris. Photo: Bartek Busko

Szapocznikow was diagnosed with tubercular cancer in 1969, and the disease influenced the enormously personal work of her final years. Souvenir I (1971), which imprisons photographs of the artist as a child and a deceased victim of the concentration camps in polyester resin and fibreglass, feels like a premature elegy. The same technique was used for the sculptures that make up the installation Tumours Personified (1971), a rock garden of anthropomorphised malignancies. The brute reality of mortality acquires a tinge of fatalistic humour. The Herbarium pieces, in which polyester casts are crushed and stuck to boards, are more wrenching still; an Autoportrait (1971) from this series sees the artist morphed into a series of yellowing smudges, as if drained of moisture or packed for storage. It’s an uncompromising coda to a unique career, which is finally being accorded the acclaim it deserves.

‘Alina Szapocznikow: Human Landscapes’ is at the Hepworth Wakefield until 28 January 2018.