At the start of his Principal Navigations, the Elizabethan propagandist of empire Richard Hakluyt recalled how his interest in the New World was first piqued. Visiting his cousin in Middle Temple, London, he marvelled at the map of the world spread across his table. This cousin pointed out all the seas, empires and kingdoms known to man and discoursed on their produce, wants and wares. Then, being a good Protestant, he pulled a Bible off the shelf and opened it at Psalm 107, where, said Hakluyt, ‘I read that they which go down to the sea in ships, and occupy by the great waters, they see the works of the Lord, and his wonders in the deep.’ Hakluyt resolved thereafter ‘by God’s assistance’ to ‘prosecute that knowledge and kind of literature, the doors whereof […] were so happily opened before me’.

Theodore de Bry was a Protestant refugee of around 60 when he first encountered Hakluyt in London in 1586. He had made his living as a jobbing goldsmith in Antwerp, but had been forced to flee the city two years earlier when it came under siege from Catholic forces. It was a crucial meeting, since Hakluyt, perhaps summoning up the same zeal that his cousin had worked on him, set De Bry on a new course. Hakluyt had already penned and published treatises on exploration, but these had attracted little attention. De Bry’s task was to sex up the genre with engravings that would turn an unimaginable world into a place of reality.

De Bry’s first step along this path was the republication in 1590 of the English explorer Thomas Harriot’s description of Virginia, with images based on Harriot’s text. By then, De Bry had relocated to Frankfurt, the publishing capital of Europe. Over the next 12 years, he and his sons produced eight further volumes on the New World, freely adapting previously published tracts on Brazil, Mexico, Peru and other parts of the Americas, adorning them with sensational pictures.

These nine volumes form the basis of America. All were originally published in separate German and Latin editions, though here the images are accompanied by a modern English translation. In most cases, the editors have chosen hand-coloured versions of the images, taken from originals in libraries in the USA and Germany. The colouring, they make clear, was almost certainly done at the behest of the purchasers rather than by the De Brys themselves. A further four volumes appeared between 1618 and 1634, though the editors have chosen not to include them here, on the grounds that the images ‘are of notably inferior artistic quality’.

As this suggests, America is very much a book for visual gratification, despite coming with scholarly commentaries. This might seem an unworthy impetus, but in this respect, the publisher’s motives are not so different from those of De Bry. Although Hakluyt may have been driven by a genuine sense of mission to disseminate knowledge of the New World, his protégé was propelled principally by a desire for profit. Like this modern edition, his works were luxury volumes. They were not aimed at students: De Bry was merrily indifferent to academic conventions, splicing together disparate texts and embellishing descriptions at will. They were rather directed at wealthy collectors. This was the age of the Kunstkammer; what De Bry was offering was a leather-bound assortment of New World wonders that could slip easily on to a shelf.

‘How a slave was killed and eaten’, plate 16 of America, vol. III (Frankfurt, 1592), Theodore de Bry. John Hay Library, Brown University, Providence

The kind of images De Bry created confirm these intentions. Some of the 600 or so engravings here were based on illustrations in the original works, but at least 40 per cent were invented from scratch by De Bry, who never left Europe, and his assistants. Realism was a distant concern: he sacrificed perspective for detail and crammed in as much as possible. In volume one, for instance, Amerindians canoe across transparent seas teeming with bucklersized crabs and gawping sea monsters. The hundreds of indigenous peoples who appear across the nine volumes are remarkably similar in appearance, whether they come from Hispaniola or Argentina. The men, almost invariably nude and bristling with muscles, bear an improbable resemblance to the marble deities of ancient Greece.

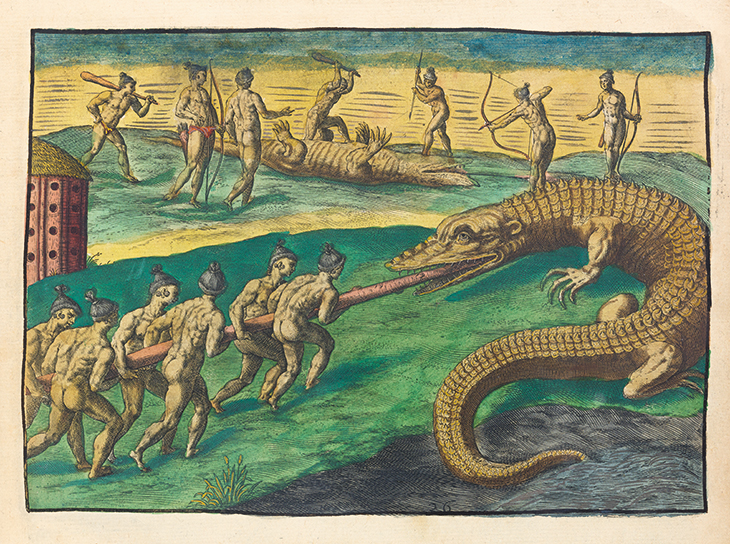

In the first volume, De Bry largely confined himself to studies of native peoples and wildlife. Thereafter, his work took a more lurid turn, in part no doubt to improve sales. In volume three, which focuses on Brazil, cannibalistic revels vie for attention with pitched battles between swarms of naked warriors. In volume eight, a compilation of English descriptions of the Caribbean, the people of Orinoco are seen blithely cohabiting with the skeletons of their ancestors. In volume nine, based on José de Acosta’s history of the Indies, a group of Mexican priests ritually impale a man atop a structure festooned with skulls. Even the depictions of fauna have a voyeuristic quality: a Leviathan-sized alligator has a tree trunk thrust down its throat, while a group of stags turns out on close inspection to be a hunting party of Amerindians disguised as deer.

‘Killing alligators’, plate 26 of America, vol. II (Frankfurt, 1591), Theodore de Bry. John Hay Library, Brown University, Providence

There is no simple moral to De Bry’s work. Several of the authors whose treatises he adapted, among them Jean de Léry and Girolamo Benzoni, wrote sympathetically of the Amerindians and criticised European excesses in the New World. The tally of sin here is pretty even on both sides. Amerindians are shown sacrificing their children, barbecuing their enemies and pouring liquid gold down the throats of Spaniards. The Christian interlopers – largely, of course, Catholics – are scarcely more humane, slaughtering and raping their way through communities, torching villages and felling forests. Amerindians worship idols and butcher the priests sent to convert them; Christians fight with Christians and slay each other for gold.

By the end, we have come a long way from the works of the Lord and his wonders in the deep. Indeed, the frontispiece of volume four offers a strikingly different vision of the New World to that conjured up by Hakluyt. A European ship sails into an apparently Edenic landscape of fruit and verdure. Presiding over it, however, is a horned, devil-like creature, pitchfork in hand. The message seems to be that, for all its abundance, this is a place of innate turpitude, corrupting anyone who ventures in. Five hundred years on, can we simply marvel at De Bry’s artifice, or are we too trading in catastrophe?

Frontispiece to America, vol. IV (Frankfurt, 1594), Theodore de Bry. Photo: John Carter Brown Library, Brown University, Providence

America: The Complete Plates, 1590-1602 by Theodore de Bry; Michiel van Groesen and Larry E. Tise (eds.) is published by Taschen.

From the November 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.