Utopia by Sir Thomas More was first published half a millennium ago this year. The book describes the strange way of life of people on a distant island. It was not presented as an ideal, as the heretic-burning Lord Chancellor (as he became in 1529) cannot seriously have been recommending a society dependent on slavery, with no private property, no lawyers, communal eating, pacificism, and a tolerance of a variety of religious beliefs. Nevertheless, ‘utopian’ has been applied to the very many attempts at creating an ideal harmonious society that have been proposed and, occasionally, tried over the last five centuries, from Robert Owen’s attempt at industrial harmony in New Lanark to the Shaker communities in the United States.

As architecture both expresses ideas and profoundly affects the way people behave, it is scarcely surprising that architects have enjoyed themselves envisaging Utopia, whether C.N. Ledoux’s ideal city of Chaux, developed from his design for the Royal salt-works at La Chaux-de-Fonds, or Archigram’s ‘Walking City’. And, occasionally, attempts have been made to build Utopia, but given the intolerant megalomania of so many ‘visionary’ architects, it is a mercy that they remained on paper; Le Corbusier’s proposal for a city of three million people housed in towers now seems more dystopian than utopian. Rather more benign, and successful, was the utopian Garden City idea promoted by Ebenezer Howard and realised at Letchworth, Bournville, and even Milton Keynes.

One of the more endearing utopias was that described by William Morris in his News from Nowhere published in 1890 (for ‘utopia’ means ‘nowhere’). This vision of a socialist communal future envisaged London as a series of low-density, high-quality garden suburbs, perhaps designed by Norman Shaw or Ernest George, in which just a few buildings from the past survive: Westminster Abbey (cleared of its monuments) and the Houses of Parliament (a market and store for manure). In the story, the time-traveller narrator visits another survival, the British Museum, to learn from an old antiquary how the ideal future came about, and is surprised that life is still based on households rather than public communities. ‘“Phalangsteries, eh?” said he. “Well, we live as we like […] Remember, again, that poverty is extinct, and that the Fourierist phalangsteries and all their kind, as was but natural at the time, implied nothing but a refuge from mere destitution. Such a way of life as that, could only have been conceived of by people surrounded by the worst form of poverty.”’

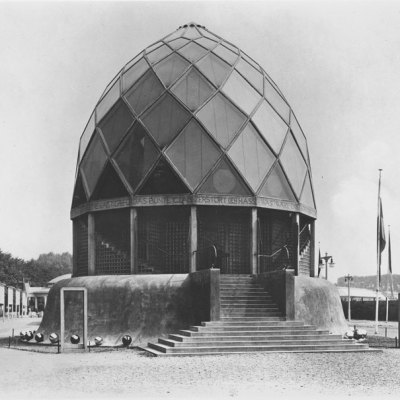

The central living block at Le Familistère de Guise. The furniture in the foreground is part of Francis Cape’s ‘Utopian Benches’ exhibition. Photo: Gavin Stamp

I quote this, as the French philosopher Charles Fourier (1772–1837) and his proposal for an ideal community, the Phalanx, was the inspiration for one of the most impressive and intelligent attempts to build Utopia – one which, on the whole, functioned for a century and which still stands today, although no longer housing an industrial community as its founder intended. This is Le Familistère in the ancient French city of Guise, the creation of the industrialist Jean-Baptiste André Godin. Born in 1817, Godin opened a small factory in 1840 producing cast-iron stoves. Soon afterwards he discovered Fourier’s ideas and became a phalansterian socialist, financing in 1853 an experimental Fourierist colony in, of all places, Texas. His own experiment was begun in 1859, next to his foundry at Guise. This was not just a well-planned philanthropic settlement for his workforce, like Saltaire near Bradford, built by Sir Titus Salt next to his mill, but an experiment in social justice in which the factory workers enjoyed the benefits of the wealth produced and were involved in management and decision making.

Fourier’s ideal community or Phalanx was intended to consist of precisely 1,620 people living and working in a large palatial building, vaguely modelled on Versailles but with covered street galleries, where the many facilities offered (and a controversial system of free love) could be enjoyed. Godin developed this concept. Le Familistère, or the ‘Palais social’, was designed to house some 2,000 people in about 500 apartments. These were in three connected quadrangular, glass-roofed blocks, placed close to, but quite separate from the factory. These were constructed one by one, the last being completed in 1884 and the larger central block being used for gatherings and celebrations. There was also a separate theatre, placed centrally on an axis, schools, a laundry and swimming bath, gardens and other amenities while a large basement under the main building included the essential wine cellars.

Godin – who did not live in a separate house but in one of the apartments (everyone was housed according to need) – would seem to have been his own architect. The exterior of Le Familistère is typical of mid 19th-century French institutional architecture, built of patterned red brick. It is the interiors of the three communal blocks which are remarkable, with all the apartments arranged behind continuous balconies on four floors around large courts covered by overall roofs of timber and glass. There was no immediate precedent for this. The new urban railway stations as well as the Crystal Palace in London had large roofs of iron and glass but were quite different in character and function; the arcades of Paris were a more likely model, with spaces between masonry buildings covered by glazed roofs but on a much smaller scale.

Godin’s experiment certainly attracted attention, and it would be interesting to know whether Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson knew of it when he proposed wide glass-roofed residential streets as part of the 1868 Glasgow City Improvement Scheme, arguing that, ‘the warmth which would result from this method of building would be conducive to the health and comfort of all’. As for Godin, he wrote in 1871 that, ‘There is no point in creating cheap housing, because cheap housing is the most expensive for people; what needs to be built is housing that allows real domestic economies, a place where human well-being and happiness can be nurtured.’

Godin died in 1888. Eight years earlier he had set up the Co-operative Association of Capital and Labour, so that Le Familistère and the foundry passed into the shared ownership of all who lived and worked there. The experiment survived severe damage from fighting at both the beginning and end of the Great War, but failed to adapt to changed economic conditions and social tensions after the Second World War. With sad irony, the co-operative was dissolved in 1968, that very year of violent unrest when ideas of worker collectives were being proclaimed in the streets of Paris. But this was not the end. The buildings survived while the factory was sold and continues to manufacture [coast-iron] kitchenware. And in 2000 the ‘syndicat mixte du Familistère Godin’ was established to create a new cultural, tourist, social and economic utopia at Guise, a living museum and focus for cultural and educational activities. Godin’s buildings have been restored, with new apartments created in the right wing while the left wing, rebuilt after 1918, is to become an hotel.

There is no other site like this in Europe: a place to consider the very idea of Utopia, where it is possible to see the future as it was – and find that it worked.

From the September issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.