As his powerful images of northern England go on display at the Getty Center in LA, the British photographer Chris Killip tells Apollo about how they seem as relevant today as when first published 30 years ago

Your exhibition at the Getty focuses on the In Flagrante photobook, which first appeared in 1988 and documents the impact of deindustrialisation in northern England in the 1970s and 1980s. How does it feel to revisit these images?

In hindsight, I think I was the chronicler of the deindustrial revolution. Living in Newcastle for 15 years, I witnessed first-hand the process of deindustrialisation, the ending of all the heavy industries – coal mining, shipbuilding, steelworks. I didn’t consciously go out to photograph this; I photographed what was happening. These works are strangely resonant in America now because of the decline of manufacturing in the country – and the idea of large-scale employment being a thing of the past.

In 2015, I released In Flagrante Two which offers a reappraisal of the 1988 work; there are now two versions of the same book. It’s very nice to have the original on show at the Getty. They actually purchased the complete set of vintage prints in 2012; ironically, no institution in England has a complete set. Because there has been so much discussion about In Flagrante over the years I wanted to make a second edition where the pictures don’t go across the gutter, and the reproductions are much better. I also added three pictures that I chose not to include first time around.

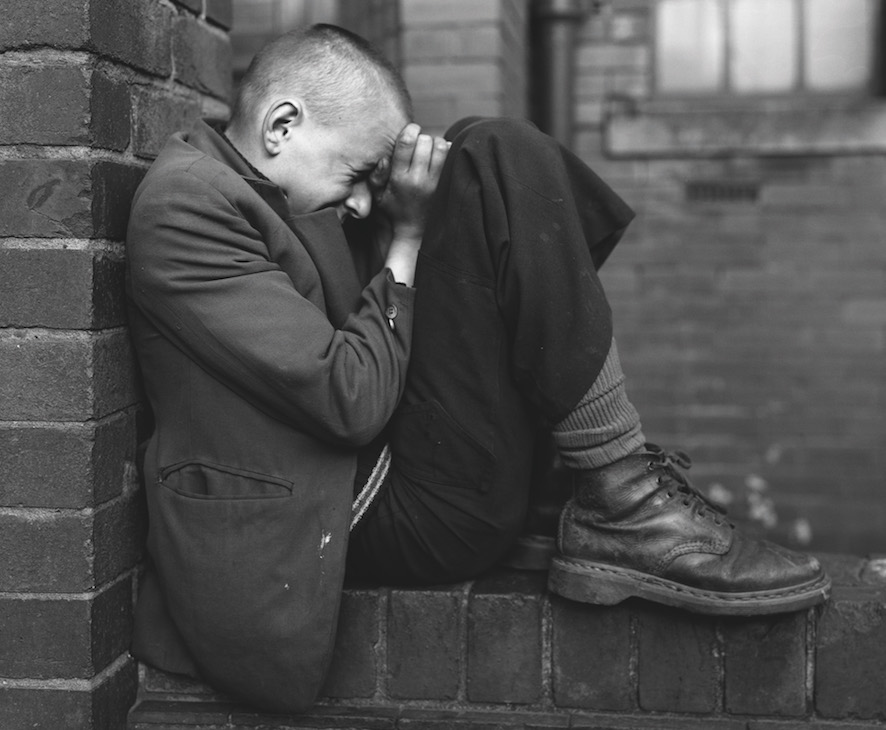

Youth on Wall, Jarrow, Tyneside (1976; negative); (1986; print), Chris Killip. J. Paul Getty Museum, LA. Courtesy the artist

Your work is often seen in the context of Thatcher’s Britain. Do you see yourself as a political photographer?

I don’t see myself as a political photographer, but I have a political viewpoint. I’m more of a sociological photographer. I got a bit fed up with people always categorising my pictures along with the Thatcher years; the meaning was taken away from me. That is why there is only one short text in In Flagrante Two: ‘The photographs date from 1973 to 1985 when the prime ministers were: Edward Heath, Conservative (1970–1974), Harold Wilson, Labour (1974–1976), James Callaghan, Labour (1976–1979), Margaret Thatcher, Conservative (1979–1990).’ Youth on Wall, Jarrow, Tyneside has been seen to represent all that was wrong with Thatcher’s government, but it was taken three years before she gained power. I am not on a tirade against Thatcher – I wanted to point out that they are all equally to blame.

You once said that in your images of the working class you try to capture ‘the sublime in the everyday’. How does this play out in your photographs?

I said that in relation to my photographs of Skinningrove, a tough, insular little fishing village in North Yorkshire. I thought the place had a great deal of Romanticism, in the German sense of the word. This was to do with the elemental nature of Skinningrove, which is so exposed to the sea. At that time there was something very specific and wonderful about this place because people there were obsessed by the sea, fishing was a sort of mania. People no longer fish there.

Crabs and People, Skinningrove, North Yorkshire (1981), Chris Killip. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Courtesy the artist

Does it feel like those pictures belong to a time that has disappeared?

Yes. They belong to a time before, when there was much more employment. Similarly, my book Seacoal [2011] focuses on Lynemouth, a village some 14 miles north of Newcastle. When I photographed there, I was living in a caravan on the headland over the sea; people were getting coal from the sea, and there was a power station that was sending its electricity one mile away to the Alcan aluminium smelter. Now it’s been landscaped. These coal mining villages only existed because of the mine, and now the mine has gone they’re in a sort of limbo. They are very strange places to be. I didn’t know I was capturing a disappearing way of life.

The concept of work is central to your photography – your 2012 retrospective at the Museum Folkwang in Essen was called ‘Arbeit/Work’.

Yes, a lot of my pictures are about the working class and the struggle for work. An important book for me is Pirelli Work [2006], which is not only about the struggle but about being in work – it’s a close-up look at labour, a series of portraits of people working very intensely. I spent five months at the Pirelli factory photographing and so I got very close to people; I was part of the furniture. Clive Dilnot wrote a text for that book, in which he said that he primarily thought of me as a portrait photographer. I had never thought of myself in that way. It’s made me look at my work again; I’m preparing to do an exhibition just of portraits.

Tire Builder, Pirelli Factory, Burton on Trent, Staffordshire, 1989 (1989), Chris Killip. Courtesy the artist

Your photographs are the result of spending extended periods of time in local communities. What impact does that have on your work?

The Czech photographer Josef Koudelka stayed with me in 1975 when I moved to Newcastle. He said that if you brought six Magnum photographers to Newcastle to do a project over a six-week period, all the pictures would be good but they’d have certain similarities. But if you stayed for six months, or a year, you would take different pictures just by being there longer and getting under the surface of things. I thought there was a lot of truth in that; it felt so relevant to me. Staying in the same place means you will do something different from someone passing through. It was important that I was committed to the area I was working in – such as the north-east of England, which I liked so much.

Why are you so drawn to the photobook as a means to display your work?

A book has a very distinct beginning, middle and end – it has a narrative drive. And photography doesn’t suffer as much as painting in terms of reproduction, especially now the quality of reproduction is so high. In designing In Flagrante Two I deliberately made the border slightly bigger so people could cut the pictures out and frame them. People who wanted my pictures and couldn’t afford them could just buy the book. I was very aware of this when redoing In Flagrante, because the original book has become – problematically – very desirable, a commodity on the second-hand book market. To bring it back and make it available was very important to me.

Father and Son Watching a Parade, West End, Newcastle (1980; negative); (1986; print), Chris Killip. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Courtesy the artist

Your work is often discussed alongside that of other post-war documentary photographers. Do you think of yourself as working within a tradition?

Yes I do. For me it goes from Bill Brandt to Roger Mayne. But I’m perhaps more influenced by Walker Evans – his stringency, his aloof coolness, his absolute precision.

You’ve taught at Harvard since 1991. Has teaching in America – a place you’ve never photographed – influenced your work?

Yes, teaching has made me more articulate about my work and it has given me an enormous amount of stability. But in actual fact, I don’t feel like I live in America: I live at Harvard, in the ivory tower! Unlike when I’m in England, in America, particularly in a social context, I am never that sure I have a grasp of the situation. That’s because I haven’t really lived in America. It does sound so strange to say.

‘Now Then: Chris Killip and the Making of In Flagrante’ is at the Getty Center, LA, from 23 May–13 August.

From the May 2017 issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.