From the February issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

A second Roman floor was found at the site of the Lod mosaic in 2009. Archaeologist Amir Gorzalczany, of the Israel Antiquities Authority, tells Imelda Barnard what this recently unveiled discovery reveals about the villa that housed them 1,700 years ago

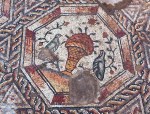

View of the Roman mosaic floor discovered in 2009 on an archaeological site in Lod, southeast of Tel Aviv. Photo: Griffin Aerial Photography; courtesy the Israel Antiquities Authority

How important is this new find, and how difficult was it to locate?

It is very important because it completes our knowledge of the Roman villa. When we discovered the Lod mosaic in 1996, we couldn’t complete its excavation because of budget restrictions; it was also unclear what would happen to it. We began a new excavation in 2009, after a visitors’ centre got the go-ahead, which is when this new mosaic was discovered. Again, we didn’t finish the excavation, because the majority of the new mosaic was located underneath a main road. Only in 2014, after the road was diverted, could we finally uncover the whole mosaic. As a result we now know that the villa had at least four wings; the Lod mosaic served as the living-room floor and this new mosaic, which forms the southern part of the complex, was a ‘peristyle’ – a courtyard pavement surrounded by columns and corridors.

Did its discovery change the plans for the construction of the visitor centre on the site?

Of course – we realised that the villa was much larger than previously thought. Our knowledge before was very partial but we now have a sense of the whole villa and its surroundings. We also have a better understanding of the layout and distribution of the buildings in Lod. There would be no point in displaying just one part of the villa so the new museum will show both mosaics. Following its travels [the Lod mosaic has been on display at various museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Waddesdon Manor], it is on its way back to the site in Lod, southeast of Tel Aviv. We want visitors to experience the whole villa on the one site.

What does the new mosaic depict?

It’s a very rich, late Roman work, composed of rectangular concentric frames. Inside are nine medallions, octagonal in shape: five of these depict animals fighting or hunting; two depict fish, showing species from the Mediterranean Sea; and two others reveal birds – doves and partridges beside objects, including an amphora and a basket of flowers. Based on the ceramic shards found during the excavation, and on numismatic – as well as artistic – grounds, we have dated it to the 3rd century. This mosaic is the best of the Roman tradition.

How difficult is it to conserve mosaics?

The difficulties are numerous. First you must stabilise the site to avoid stones falling; the conservation team worked alongside excavators as soon as this new part of the mosaic was exposed. A frame had to be constructed around every panel, and then the mosaic was separated very carefully from the ground: it splits into different panels, which allows it to be handled and transported more easily. Before this, the mosaic underwent a thorough cleaning, stone by stone – staff spent weeks working on their knees using toothbrushes and surgery scalpels. One of the main difficulties lies in the fact that the mosaic is composed of materials from the Roman period. As with all archaeological excavations, prior to dismounting, the mosaic was documented with high-resolution pictures and drawings. This was crucial because it will be dismantled and assembled again many times in order to be exhibited. But removing the mosaic taught us a lot about the people who originally laid it. We even revealed the footprints of the original artisans in the plaster; these will be put on display in the visitors’ centre.

Can you explain why this site is so archaeologically rich, and how difficult is it to excavate such sites?

In the Roman period, Lod was the capital of the district. We have found many mosaics all over the area so we know that this village was a wealthy neighbourhood. Like many others cities in Israel – Jaffa, Ramla, Acre, Jerusalem – Lod is an invaluable source of historical and archaeological knowledge. These cities have been inhabited without interruption for hundreds of years, and so they present almost insurmountable problems when you try to excavate, especially in the old quarters where archaeological remains tend to accumulate. There are problems of infrastructure, safety and logistics. People live and work in these areas, and an excavation will always be a nuisance. Not to mention the numerous religious, political and social conflicts. Therefore, archaeological research in ancient cities is a very difficult, albeit gratifying task. Archaeology is also about working with people to convince them that antiquities are an asset that must be explored and protected.

What about the wider work of the Israel Antiquities Authority? What is its function in Israel?

The IAA is in charge of all matters relating to antiquities in Israel; we manage excavations in the country, on both land and sea. We are in charge of national collections including, for example, the Dead Sea Scrolls. We are heavily involved in research and produce a range of publications relating to our findings. We try to educate people to be proud of the past, to be connected to the land, to history, to traditions. In Israel there are more than 30,000 archaeological sites that are declared and legally protected. When somebody, be it a municipality, electric company or contractor, performs any task involving excavations in an archaeologically declared area, the IAA closely supervises the works in order to avoid damages to antiquities. This was the case in 1996: the Lod mosaic was discovered during necessary infrastructure works. What was a routine, even boring task, led to this fantastic discovery.

Being an archaeologist is not a job for me – it is what I am. It is part of me. We are very proud of our work.

Could the international archaeological community do more to protect the cultural heritage under threat in the Middle East?

It’s a big issue. I’m sure that much more could be done – I expect governments to do a lot more. Don’t forget though that most of the antiquities aren’t being destroyed but are being looted and sold on the black market – and they are on the black market because somebody is buying them. Nobody has the time to think about archaeology or history when people are dying but our shared heritage is being lost. Of course we must protect people’s lives, but we must also save our cultural heritage.

Click here for more information on the Israel Antiquities Authority.