When the artist Eric Ravilious’s aircraft was lost over Iceland in September 1942, his wife Tirzah Garwood (1908–51) was recovering from a mastectomy operation, having been diagnosed with breast cancer. She was also looking after their three children, aged seven, three and 18 months. Through all this, she continued typing up the autobiography she had begun writing six months earlier in lined notebooks. Not long after, she began to paint oils too, and went on with these during her second marriage to radio producer Henry Swanzy, despite the return of her cancer. In her last year, which she called ‘the happiest year of her life’, she painted 20 oils.

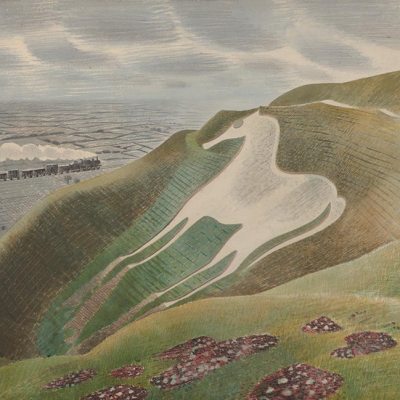

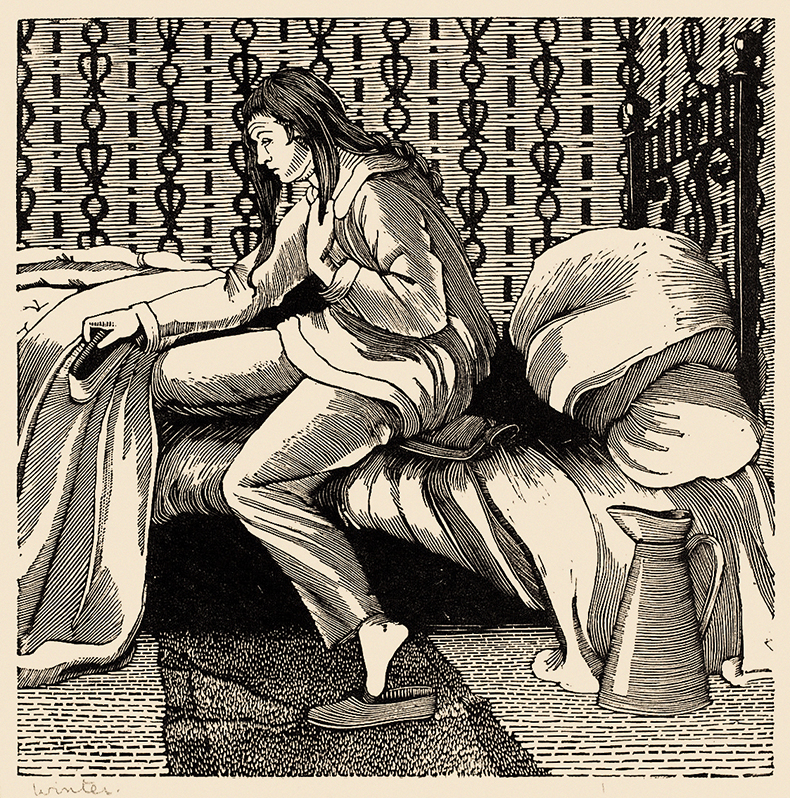

The Four Seasons: Winter (1927), Tirzah Garwood. Courtesy Fleece Press

Many of these, together with her earlier wood engravings and patterned paper designs, are currently on display at Dulwich Picture Gallery (until 26 May), in an exhibition focused on Garwood’s work rather than that of her better-known husband. It is a celebration of her artistic output that is well overdue. But Garwood’s autobiography Long Live Great Bardfield reveals her to be as important a writer as she is an artist: for, casually and unselfconsciously over its pages, she reveals a unique voice. She was not a writer during her time at Eastbourne School of Art as a student of Ravilious, or during her marriage to him, or during the years at Great Bardfield in Essex – where she and Ravilious shared a house with Edward and Charlotte Bawden; but when she was convalescing in the spring of 1942 she became one. Without fumbling, she found her own inimitable tone – understated yet uninhibited, human, matter of fact: ‘In 1903, on a wet afternoon in Croydon, my father was married to my mother.’ Funny, too: ‘I had bought the tortoises from Woolworth’s to save them from death in the same spirit that we [later] offered our home to German refugees.’ And she never grumbled, having the good luck ‘not to be put out by misfortunes as much as most people’. Possibly, she goes on to say, ‘this is because I habitually am lucky enough to be completely absorbed in drawing or writing so that I become quite unconscious of people or time when I am working, so there is always that escape from reality.’ So, despite everything, there is joy in her book; the kind that, mixed with an often devastating practicality and realism, you find in books such as Nancy Mitford’s The Pursuit of Love or Gwen Raverat’s Period Piece. It’s all to do with tone of voice, just as painting is to do with angle of vision.

House at Great Bardfield (1945), Tirzah Garwood. Private collection. Courtesy Fleece Press

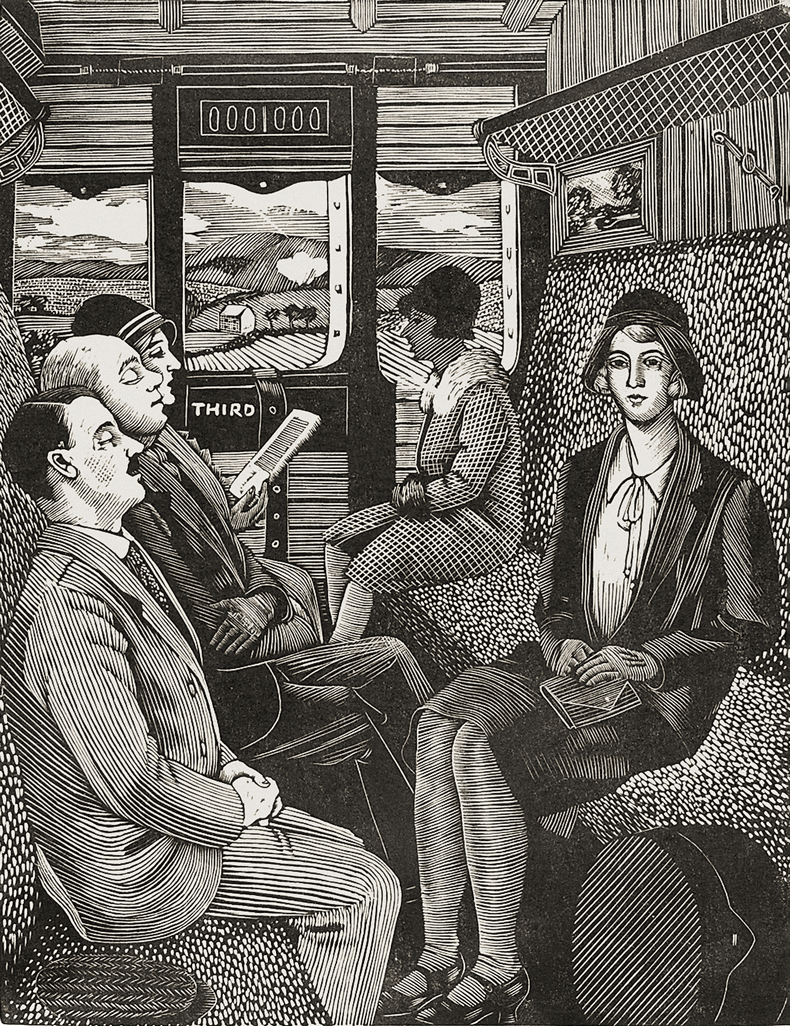

The text of Long Live Great Bardfield, which was published expensively in 2012 as a Fleece Press limited edition, was transcribed from Tirzah’s 1942 handwritten notebooks and the typescript she based on them – both later edited by her daughter Anne Ullmann. The focus of the first edition was on the copious and beautiful illustrations. In the Persephone Books edition, published in 2016, we reproduced either a photograph or a wood engraving at the beginning of every chapter; including, for example, The Train Journey (1929), in which Garwood depicted herself, cloche-hatted, sitting neatly and pensively in a third-class carriage. For the volume’s endpapers we chose one of her beautiful wood-engraved paper designs – a star-strewn, almost futuristic pattern, printed in red engravers ink – many of which she had made at Great Bardfield in the 1930s, when domestic chores had left her little time for more involved work.

Train Journey (1929), Tirzah Garwood. Private collection

Garwood’s autobiography is important not just as a portrait of a group of artists in the interwar years, but also because it expresses her individuality and humanity as she chronicles the life of a woman struggling to lead an artistic life amid the constraints of childcare and housework. ‘Before I had my children,’ she writes, ‘I tried as best I could to express my appreciation [for life] by pictures or marbling […] now I haven’t time to do anything except look after the children, I can only scribble this.’ In the words of Virginia Woolf, ‘How any woman with a family ever put pen to paper I cannot fathom. Always the bell rings and the baker calls.’

Marbled papers (1934–41) by Tirzah Garwood. Private collection

Above all, Garwood’s book is a meditation on the conflict between the bourgeois and the bohemian, between Kensington and Bloomsbury, between the artist and the wage slave. As she herself put it, recalling her earliest artistic endeavours: ‘I had sent some of my wood engravings to the exhibition of the Society of Wood Engravers and they had been liked by the committee of which Eric was a member and The Times had given them a kind mention; this more than anything convinced my parents that they ought to let me go [to art school], though they thought my subjects hideous and that Mr Ravilious was perverting a nice girl who used to draw fairies and flowers into a stranger who rounded on them and did drawings that were only too clearly caricatures of themselves.’ The theme is familiar. It’s one that Garwood explores in her writing with affection, insight and wit.

Long Live Great Bardfield: The Autobiography of Tirzah Garwood is published by Persephone Books.

‘Tirzah Garwood: Beyond Ravilious’ is at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, until 26 May 2025.