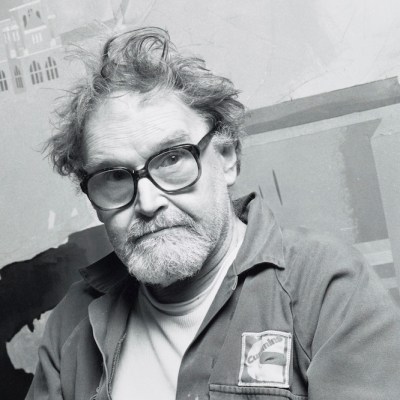

With the passing of Tom Phillips, Britain has lost one of its most brilliant and idiosyncratic artists. A talent like no other, he managed both to gain all the recognition the British art establishment could offer – a CBE (2002) to add to his status as a Royal Academician (1989), and a stint as Slade Professor of Art at Oxford (2005–06) – and to remain, somehow, underappreciated. An outsider, who despite the cult following of his best known work, perhaps never quite made the public impression he deserved.

For many, Phillips will be defined by one piece above all: A Humument. Carved out of a forgotten Victorian novel – W.H. Mallock’s Human Document – bought for three pence at a Peckham junk shop in 1966, the project occupied Phillips for 50 years. Few other artists would have seen the potential for a life’s work in such unpromising material; Phillips adored the constraint. Across six editions, he turned Mallock’s baggy melodrama into a pocket-sized jewel of illuminated poetry, excavating new texts out of the old prose, selectively obscured by an array of dazzling designs. As the cover of the final edition announced, ‘now / the / arts / connect / in / my poor little book / very rich / for / eyes’.

Phillips’ ability to mine Mallock for so long highlighted one side of his paradoxical brilliance. He was a parochial artist, and deliberately so. ‘English / Born at Clapham’, he trained at Camberwell, and spent most of his life not far from his birthplace, dying in the Peckham house he inherited from his mother four decades ago. As with A Humument, he was able to find endless inspiration in the same small patch of ground. For 20 Sites n Years, he spent decades photographing the same personal landmarks within a half-mile radius of his home, recording their appearance once a year without fail from 1973 to 2022. ‘This sculpture,’ runs the sedulous inscription to one of the gouache snapshots of Ma Vlast (My Homeland, 1971), ‘stands 1152 paces from the house where I was born’ – the sculpture is an old junction box by a section of scaffold-pole fencing. Even the appearance of Peckham’s first satellite TV dish occasioned a painting and celebratory etching (Peckham: The First Dish, 1990), complete with historical notes, written, like Leonardo’s notebooks, backwards.

But it was characteristic of Phillips that the personal and the local were seen always in the light of infinitely broader contexts. His omnivorous intellect seemed to take in everything, inflecting his work with vast literary and musical knowledge, and an endless appetite for both tradition and novelty. It was symptomatic that his south London, with no hint of bathos, should become Ma Vlast, a title borrowed from Smetena’s symphonic poems on the Bohemian landscape. Phillips was himself a composer, well known in avant-garde circles in the 1960s, creating works for piano, and in the 1970s, an opera, Irma – another by-product of A Humument – whose graphic score was an artwork all its own. John Cage’s interest in chance operations was a key influence on his music and his art alike, where the aleatory, found, and fortuitous are allowed to work their magic within careful procedural bounds – a practice he passed on to his student Brian Eno.

His literary education, too, is a central element in his iconography, where poetry is omnipresent. When asked to illustrate Dante’s Inferno (1979–83), Phillips could not in good conscience borrow someone else’s translation, and spent three years on his own blank verse translation – and weathered Samuel Beckett’s criticisms of it while drawing him in 1984. His art historical knowledge was similarly capacious. Proud that, by his own calculation, he was ‘at only twenty removes […] a pupil of Raphael’, his curiosity also made him a scholar and collector of African art, and led him to curate the Royal Academy’s major ‘Africa: The Art of a Continent’ show in 1995. While little took him north of the Thames, his art gathered in material from far and wide, with a delighted, unstinting voracity.

Despite clear affinities with fellow travellers like Peter Blake or Ian Hamilton Finlay, Phillips’ work is unlike anyone else’s. The product of a Pop art sensibility meeting the intellectual breadth of high modernism, filtered through the improvisational tactics of the New York avant-garde of the 1950s, it is uniquely approachable and endlessly stimulating. As varied as it is recognisable, his vast output ranges from prints, drawings and paintings, through to tapestries, public commissions, and sculpture, with time for a few album covers along the way. A fine portraitist, his painting of Iris Murdoch (1986) resides in the National Portrait Gallery. Perhaps his defining quality, though, was an off-kilter sense of humour. In tribute to the annual ritual of Wimbledon, Phillips created his final self-portrait as a set of tennis balls covered with his own hair trimmings, gathered over decades, fading gradually to white (The Seven Ages of Man, 2010).

There will be plenty of tributes to Phillips in the next few days, but none will be more eloquent than his own work. The final version of A Humument (2016) closed with an image of Mallock’s gravestone, picking out the words, ‘your / grave / in / mine / fused’, and the hopeful wish, ‘my best / perpetuate / page / for / page’. It surely will.