From the January 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

29 July 2021, Jeffrey Gibson at the Smart Museum of Art.

My photographs tell me that the first work I began living with, at the end of July, was a quilt collage by Jeffrey Gibson (Mississippi Band of Choctaw, Cherokee). STAND YOUR GROUND (2019): pieced fabric of images, patterns and words overlaid by patterns of stitching. The words Stand Your Ground, in rainbow letters, are worked into the quilt around the borders, in stripes across, with letters forwards and backwards, in vertical passages, with other rectangular areas of iridescent greens, blues, oranges. The title alludes to the water protectors working at the Standing Rock Reservation to halt the Dakota Access Pipeline, and also to legislation around using firearms for so-called ‘self-defence’, which in the United States are called stand your ground laws, and which have been painfully central in recent months and in the last decade of crimes against Black people and people of colour.

Whose ground is ‘your ground’ and what is it to ‘stand it’?

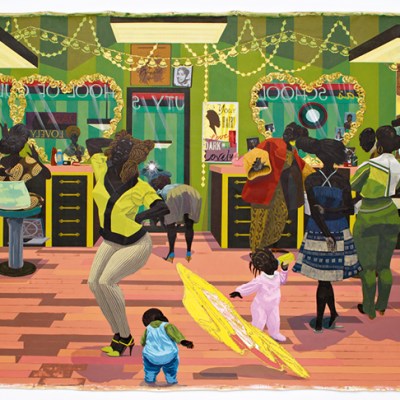

Gibson’s work at the Smart Museum was part of a city-wide show called ‘Toward Common Cause’ (15 July–19 December 2021), a set of exhibitions, installations and events that highlighted 40 years of MacArthur Foundation Fellowships. Familiarly referred to as ‘genius grants’, MacArthur Fellowships are given in all domains of art, science and the humanities. They confer a signal honour and often have a transformative effect on an artist’s career. For ‘Toward Common Cause’ 29 fellowship artists – including Whitfield Lovell, Mark Bradford, Kara Walker, Dawoud Bey, Kerry James Marshall, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, and many others of similar distinction – participated in site-specific shows created through a curatorial coalition led by the Smart and by the exhibition’s curator Abigail Winograd with 37 partner organisations. For me, the show was a three-month-long opportunity to visit, in corners of the city that are already a part of my life and thought, the work of contemporary artists who clarify my own perceptions and understanding.

All the times I went back to Jeffrey Gibson’s STAND YOUR GROUND I was drawn to a small, blued face, with yellow stitching around it. For writers, as for painters, ‘figure’, and ‘ground’ are evocative, a way of remembering and possibly moving around ideas of individuals sharply outlined, in isolation, ungrounded, maybe careless or appropriating of ground, maybe taken from their ground. My photographs from that first encounter circle, making closer examinations of that face, then moving around again.

STAND YOUR GROUND (2019), Jeffrey Gibson. Courtesy the artist and Kavi Gupta, Chicago, IL.; © Jeffrey Gibson

Mid September 2021, Whitfield Lovell, Spell Suite at the South Side Community Art Center.

We corral the kids and drive 13 blocks north to catch the Whitfield Lovell show at the venerable, caretaking, South Side Community Arts Center. Lovell laid out Spell Suite – six works from 2021 and one radio installation from 2008 – especially for this pine-panelled space, so important in the history of Black Arts in Chicago. Each of the six drawn faces is highly finished in conte on paper; bodies are suggested with a few trailing lines. Each drawing is presented in a frame with a different object – a wooden serving dish with plastic grapes (Fig. 2), four small American flags, an old blue book (The American Race Problem) on a special shelf – objects that seem to request imagination. The children are antsy, but they look at the drawings, consider the objects. In the corner, a square pile of 37 radios stacked in five unsteady columns, several of them playing bits of old song and talk.

Lines radiate from Spell Suite towards other ‘Common Cause’ shows, each asking questions about figure and ground. Towards ‘Sweet Bitter Love’, a series of Jeffrey Gibson’s layered portraits and history; to a huge circle of work by Kara Walker; and to another work by Whitfield Lovell seen with the children on another South Side afternoon.

Spell no. 17 (Richesse Noire) (2021), Whitfield Lovell. Courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York; © Whitfield Lovell

17 September 2021, Jeffrey Gibson, Sweet Bitter Love at the Newberry Library.

Six large layered paintings with beadwork and small found objects. Each one a portraying-over-again of a person – Chief Pretty Eagle, Chief Black Coyote, Pahl Lee, White Swan – who had been painted by the late 19th-century ethnographic artist E.A. Burbank. Unlike the earlier Burbank portraits, Gibson’s works show the same faces in several contexts, sometimes just the eyes or part of the face, gathered with vintage beadwork and his own beadwork, with framing patterns, with blurring and wearing and strongly coloured geometric designs. There are also two glass cases with ethnographic cards from the nearby Field Museum documenting the acquisition in 1990 of a variety of objects that had been ceremonial gifts given by Yupik Eskimo people as part of a seal party. Each card is accompanied by a Gibson drawing of the object: a tin of tobacco, a roll of toilet paper, lengths of cloth. These object drawings were then made into a large repeating pattern of colourful wallpaper, on which are installed the series of Burbank paintings that belong to the Newberry Library. Being between the two walls – of the large Gibson portraits and the collected items from the Field and Newberry – is like being in a hall of mirrors, but deeper than that; not shiny flat reflection but colour and thought calling across.

30 September 2021, Kara Walker at the Roundhouse of the DuSable Museum of African American History.

Some say the Roundhouse is the most beautiful building in Chicago. Built by architect Daniel H. Burnham in the early 19th century, initially used as a stable, long disused, and now partially restored for exhibitions of the DuSable Museum – once a hub, still a place for remembering, an odd combination of roundedness and starkness.

The black silhouettes of Kara Walker’s brave and tormented figures process across the nightmare of white, white ground. Rainbow-coloured glass by Cauleen Smith above (a permanent fixture) projects curved paths of coloured light in an arc on the ground and up the walls. It is very quiet in the space, but I feel injury, horror, ruthlessly enforced distinction, and – is this from the artist, the figures, both? – a resistant mockery loud enough to be audible.

14 November 2021, Whitfield Lovell at the Rebuild Foundation’s Stony Island Arts Bank.

Bundle the children into the backseat to drive 17 blocks south to the old bank building on Stony Island Avenue that has been rehabilitated as an elegant gallery and research library. Threading their way through the group show, the children sit down in front of a Whitfield Lovell, Missoura, from 2001. Four men in hats and suits, three with walking sticks, one with a book. Before them on the ground, an actual drum. A round drum with two drumsticks, one surface of the drum gashed open. The figures are drawn in charcoal, which is burned wood, on wood panels.

The children remember having seen the other Whitfield Lovell portraits, with the objects. They ask questions about the drum; we all sit down on the floor and begin to talk about history, what families can remember, breaks across generations. About how figures may become ground, how ground may yield up figures.

From the January 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.