The Trump administration’s abrupt unravelling of the fabric binding cultural and educational institutions has taken everyone by surprise. That includes those of us old enough to have endured the ‘culture wars’ of the 1990s. Dennis Barrie, director of the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, then risked imprisonment to defend the museum’s right to display explicit photography by Robert Mapplethorpe. In 1999 the Brooklyn Museum’s director, Arnold Lehman, and his board thwarted then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s performative, unconstitutional attempt to defund the museum over Chris Ofili’s painting of a Black Madonna. But courage was otherwise in limited supply.

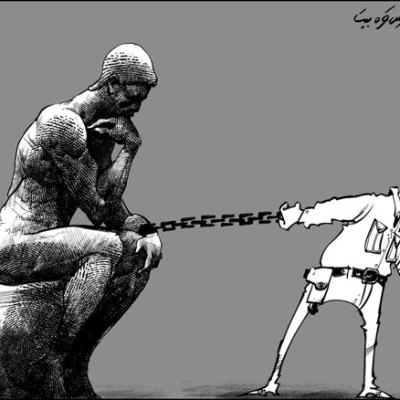

Two decades later George Floyd was murdered by police, and the museum world seemed to take note of the persistent scourge of racism. It became obligatory to protest police brutality and express solidarity with those fighting for racial equity. Expressions of concern morphed into a flurry of hirings intended to signal acceptance of our collective responsibility to battle discrimination on multiple fronts. The Association of Art Museum Directors issued bromides about a changed world.

And then Trump returned. Over the first few months of 2025 the national atmosphere has flipped to one reminiscent of the pall cast by Senator Joseph McCarthy, stoking fear instead of remorse, and quieting advocacy of racial equity so as not to attract the notice of a new cultural inquisition. Months into Trump’s proclamation of a new ‘Golden Age’ – a phrase invoked by authoritarians everywhere – we are still waiting for the next Dennis Barrie to raise her or his voice of protest against the scrapping of diversity programmes at the National Gallery and Smithsonian Institution, the evisceration of the National Endowment of the Arts and National Endowment of the Humanities, and the shuttering of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

Trump’s first administration limited its attacks on unfettered cultural expression to mandating ‘classical architecture’ for federal buildings, a misbegotten edict that was frustrated by the long timelines involved. The second Trump administration is putting significant energy and resources into attacking universities and museums, believing them to be strongholds of liberal attitudes and liberal supporters. By withholding hundreds of millions of dollars of federal funds for academic research, the White House has decided that the benefits of scientific enquiry are dispensable, but the fealty of university administrations is essential. The president’s effective appointment of himself as chair of the Kennedy Center on 12 February is both ridiculous and part of a process of bringing cultural institutions into line.

Not all is yet lost. In New York, the spring programmes at three of the city’s four leading museums include monographic shows by Black artists: Amy Sherald at the Whitney, Jack Whitten at MoMA and Rashid Johnson at the Guggenheim. Since exhibitions of scale take years to prepare, this can’t be read as a response to Trumpism. As wealthy private institutions are largely out of the reach of the federal government, each one’s advocacy of accomplished Black artists will reverberate in the nation’s art capital.

But outside of New York, such advocacy can’t be taken for granted. Museum trustees witnessing the demonisation of programmes focused on diversity will likely counsel their directors to go easy on curatorial fare that might irritate local and national lawmakers. Self-censorship will foreclose the possibility of exhibitions and initiatives that just a few months ago could have expected a warm welcome.

The sudden upending of values is devastating, coming as it does after four years that were dedicated to championing new voices. What lies ahead is uncertain. Should the midterm elections in November 2026 restore control of the House of Representatives to the Democratic Party, some of these totalitarian measures may be slowed, but not stopped. In the meantime, arts leaders, arts supporters, academics and cultural administrators should not wait for press reports or court rulings before making their voices heard. The message? Don’t capitulate to the instinct to stay out of sight. Don’t cede authority out of fear. Take a stand in support of your mission. Lead your boards to acknowledge that this is not a normal time, and that free speech must be defended at all costs. The survival of your reputation and that of your institution will depend on acts of courage.

Maxwell L. Anderson is president of the Souls Grown Deep Community Partnership & Foundation and a past president of the Association of Art Museum Directors.