The Turner Prize in 2025 is a curious, chimerical sort of beast. Now more than 40 years old, it is about as embedded in the British art establishment as it’s possible to be, yet still likes to cast itself as the insurgent outsider. It is tasked with representing contemporary British art – and by extension, contemporary Britain – yet takes place amid an ever more fractured symbolic landscape. As a result, the Prize increasingly feels both proud and somewhat chary of its own past controversies. We are left with an exhibition full of radical gestures that is not itself all that radical.

I’ve arrived in Bradford on the day that some American evangelical groups had predicted the coming of the Rapture. Entering the first of the exhibition’s four galleries, I’m immediately reminded that here in the UK, our own end-times event came and went five years ago and a lot of people seem upset about how it turned out. Up and down the country, groups of angry men hang flags from lamp posts and paint them on roundabouts in mourning for Brexit’s lost dream of sovereignty. It is the same English flag that we see in a small photo housed in a very large Perspex frame in the exhibition. In the picture, the lower half of a St George Cross hangs over the window to a dining room or event space, with a sign saying ‘private party’ taped to the glass. The implications of the flag’s exclusions do not need spelling out.

But this is far from the only flag in Rene Matić’s installation. The ‘private party’ picture is part of a work called Feelings Wheel (2022–ongoing) that consists of 40 photographs in various sizes. Among this montage of images depicting modern Britain through parties, protests and other rituals, we can see Palestinian flags, a floral wreath of the Jamaican flag, more Union flags, a Trans Pride flag knitted into a kippah, a cardboard banner reading ‘Pissed Off Trannies’, plus other markers of identity and belonging, from Black Lives Matter graffiti to the logo of the clothing brand Moschino. In the centre of the room a huge cotton flag in creamy off-white reads ‘No Place’ on one side and, in a neat bit of enjambment, ‘For Violence’ on the other. Evidently the artist recognises themself among all these symbols. We see Matić’s determined stare peering out of a black-and-white mirror selfie in the midst of the collage. For Matić, it seems, the answer to Britain’s ongoing crisis of identity is not no flags, but as many as possible, all jumbled up together in a contradiction more apparent than real.

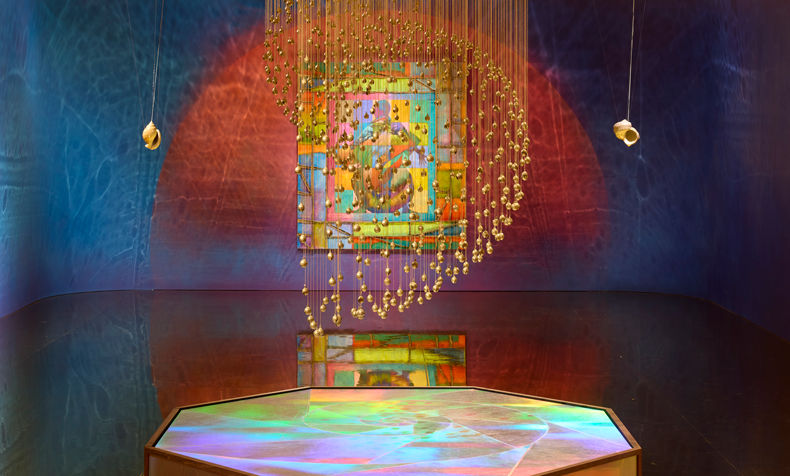

Zadie Xa offers a very different take on the vexed question of identity. Her gallery feels less confrontational, almost womb-like in its warm colours and soothing sounds. The brass bells that hang from bamboo string in a shell-like spiral and the bojagi-like appearance of Xa’s vividly hued canvases allude to the traditions of her Korean heritage. The images themselves make reference to certain shamanic practices. Ambient electronic music mixed with whale calls and spoken excerpts from science-fiction stories plays from four large shells hanging in each corner of the room. But the interruption of this soundscape by telephone dial tones and a generic answerphone message (‘Please hold. Your call is very important to us’) undercuts it all, hinting at the appropriation of Asian spirituality by the corporate New Age industry. All the women we see in the paintings wearing traditional Korean dress have their faces shrouded, turned away or otherwise obscured.

There is a kaleidoscopic exuberance to Nnena Kalu’s work. It is the brightest and boldest of the exhibition, with all the playfulness of a wild rumpus at a branch of Hobbycraft. There are ten large and bulbous hanging sculptures, resembling so many giant piñatas or Chinese New Year puppets, each one bound in crêpe-like fabric, sticky tape, cling film, ribbons and security netting. I’m vaguely reminded of Hew Locke’s carnivalesque Procession (2022) at Tate Britain, only here Locke’s beribboned human figures have evolved into intergalactic tardigrades and glittering junk monsters. On the walls hang eight pen and pastel drawings, swirling and squiggling in dense abstract accretions. It’s all very spirited and vivid. But there is a darkness here too. I’ve seen drawings a bit like this before, made in the context of art therapy sessions. The text on the wall and the works’ 2021–22 dates remind me that all of this was made in the immediate aftermath of the Covid lockdowns.

Where Kalu revels and accumulates, Mohammed Sami laments and erases. In stark contrast to Matić’s contrapuntal self-portraiture, Sami has removed human presence in his works – sometimes violently. Reborn (2023) offers a portrait of a military man, but his face and much of his right shoulder are obscured by a cankerous mass of dark, highly textured paint. Even his medals seem to be melting, as if his valour were collapsing before our eyes. Elsewhere we see evacuated traces of life: a dress and a shirt sink beneath the water’s surface in Hiroshima Mon Amour (a tribute to a scene from Alain Resnais’s 1959 film of the same name); horses’ hoofprints and trampled sunflowers in Massacre; shards of broken Japanese pottery beneath a dense ash cloud in White Flash/Dark Materials; a table and chairs marked by the shadow of what might be a ceiling fan – or a military drone – in The Grinder. These are highly cinematic, richly expressive and powerful works – no doubt all the more so when they were first exhibited in that quondam seat of Empire, Blenheim Palace, last year.

All four of these presentations have a visceral power and a strong contemporary resonance. It’s all very good, well-made work with much nuance, bearing shades of darkness but also hope. Even Sami’s sometimes brutal images possess great beauty and a sense of life. Some sunflowers and palm trees grow amid the devastation. I liked all the work here. But none of it made me think, ‘Wow, I’ve never seen anything like that before.’ That might not be such a problem for most exhibitions; not all art needs to re-invent what art is. But for the Turner Prize, with its own unresolved issues of history and identity, it might be. Is this really everything British art can be in 2025?

The 2025 Turner Prize exhibition is at Cartwright Hall Art Gallery, Bradford, from 27 September–22 February 2026.