Right now, in Antananarivo, there are three exhibitions taking place about the lamba, the traditional garment worn in Madagascar by both men and women: a display of historic photos at the Musée de la Photographie de Madagascar, a retrospective on the late 20th-century textile artist Madame Zo at Fondation H and a multidisciplinary group show at Hakanto Contemporary (until 18 November). This apparent coincidence is revealing. At moments of change, nations often feel the need to re-examine themselves – think of the V&A Dundee’s recent exhibition ‘Tartan’, curated in-house while Scotland continued to debate its future in the union. The art scene of Madagascar is brimming with fresh energy – new venues popping up, émigré artists returning to the city and young people gravitating towards creative careers – so it makes sense that, amid this transformation, this quintessentially Malagasy garment would be the subject of scrutiny.

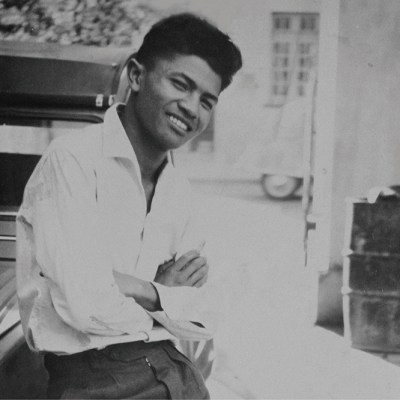

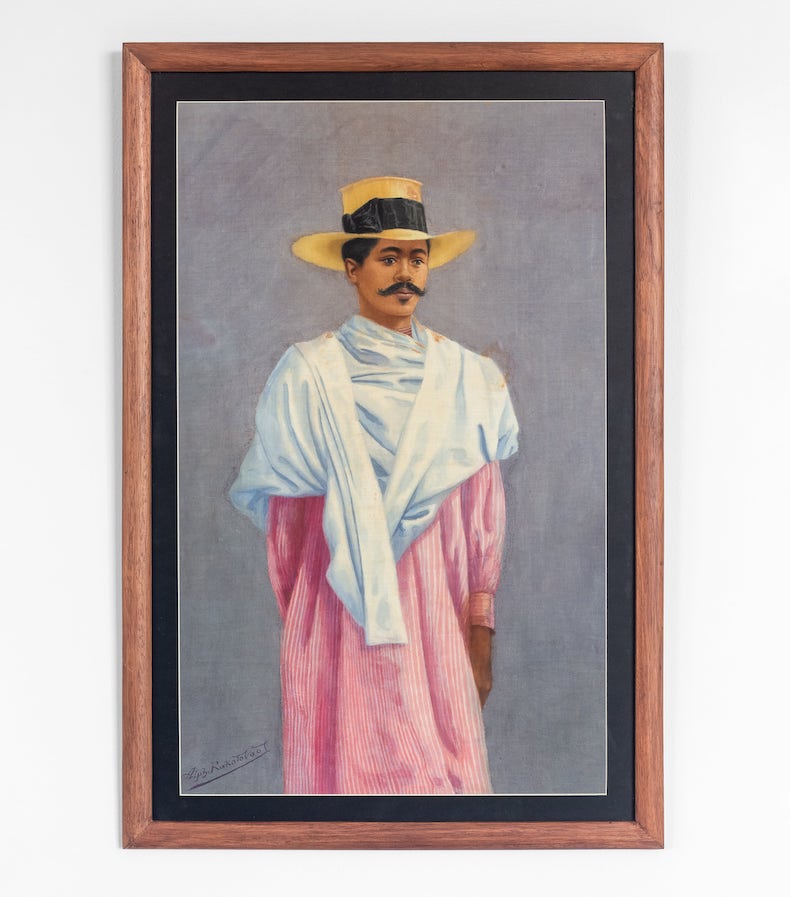

Merina au Chapeau (1930), Alphonse Rakotovao. Photo: courtesy of Hakanto Contemporary

Hakanto Contemporary was founded as a non-profit in 2020 by the artist Joël Andrianomearisoa, who intended it as a platform for emerging local and diasporic talent. The gallery’s sole supporter is Fonds Yavarhoussen: a philanthropic foundation created by Hasnaine Yavarhoussen, CEO of the Malagasy real estate and energy development company Groupe Filatex. In a city that still has few galleries and little formal infrastructure for creative careers, Hakanto Contemporary is helping to foster networks between early career artists from various disciplines, as well as offering exposure to the art world’s wider ecosystem of collecting, journalism, PR, philanthropy and sponsorship. ‘Lamba Forever Mandrakizay’ is the gallery’s latest exhibition to be curated by Andrianomearisoa, alongside colleagues Ludonie Velotrasina and Rina Ralay-Ranaivo. Scattered among contemporary works by 21 artists – photos, sculptures, video and installations – are archival images and older paintings depicting the lamba, which is wrapped and worn in countless ways depending on region and occasion.

Endlessly (2023), Kevin Ramarohetra. Photo: courtesy the artist and Hakanto Contemporary

The choice of theme is a canny one: what better way to engage a wider public with contemporary art than via a subject this close to the nation’s heart? When second-hand Western clothing began to flood Madagascar’s market in the late 20th century, for many the lamba became attire reserved for special occasions. Nevertheless, it remains central to Malagasy identity. The word ‘lamba’ simply means a piece of cloth – whether towel, rug, tablecloth or handkerchief – and so the concept is more ubiquitous than the garment alone. A series of 12 photos by Kevin Ramarohetra illustrates this through poetic depictions of the cloth’s place in everyday life: as a billowing curtain, a blindfold in a children’s game or, more disturbingly, folded to form a noose.

Apart from three vitrines filled with exquisitely crafted lambas, associated artefacts and ephemera – from newspaper clippings to embroidery tools – this isn’t a show about clothing, craft or domesticity, nor is it a commentary on a particular way of dressing, a making practice or an aesthetic tradition. This is about the lamba of the imagination – its status as a symbol of tradition, family and community, and what these things mean today.

My Messy Bed (2017), Christian Sanna. Photo: courtesy the artist and Hakanto Contemporary

The living artists in this show have interpreted this brief in a personal way. They are an eclectic (and youthful) bunch, offering perspectives as diverse as their mediums: from an enigmatic video by choreographer Nazaria Tooj titled Giving Life Up (2023) in which he burns and buries a lamba, to actor and comic Gad Bensalem’s bittersweet poem Dear Father (2023), structured to mimic the warp and weft of woven fabric.

What’s striking is the air of melancholy threaded throughout. It’s there in Nadia Randriamorasata’s geometric sculptures that make reference to the tomb her father is buried in nearby – Malagasies are wrapped in several gifted lambas when they die – and in black and white photographs by Christian Sanna of cloths tied ceremonially around a banyan tree or shrouding his own unmade bed in the form of a mosquito net, reflecting the lamba’s omnipresence in both the divine and the prosaic. In these wistful works is a clear recognition that times are changing. These young artists represent the future – not just in their own country, but in our new, post-postcolonial world order. They know it, but still seem unsure of how to move forward with sensitivity to the past. What does ‘progress’ mean in a world previously dominated by European culture? How do you honour your heritage without being ensnared by it? What do you reject and what do you carry with you? There are no answers here – only questions.

Those who are wise are lavished with teaching, while fools abandon their lamba (2023), Sandra Ramiliarisoa. Photo: courtesy the artist and Hakanto Contemporary

Nonetheless, the piece garnering most attention from visitors is one that directly confronts our present realities, while facing towards the future. Those who are wise are lavished with teaching, while fools abandon their lamba (2023) is a wall-sized patchwork piece made from a plastic waste-based fibre by the youngest exhibitor, Sandra Ramiliarisoa. The title is a reference to the foolishness of abandoning the lamba – and by extension tradition, honour and prestige – in favour of fast fashion and all its failings. The 23-year-old artist, who was selected for the show after participating in an open workshop at Hakanto Contemporary, taught herself craft techniques online before creating the tapestry in collaboration with the collective R’Art Plast. Ramiliarisoa worked with the group at a material innovation laboratory designed to help Malagasies from disadvantaged backgrounds to develop commercial enterprises. For Andrianomearisoa, Ramiliarisoa is the embodiment of one underlying purpose of his initiative – creating opportunities for self-expression and creative livelihoods among people who would otherwise not have considered these to be possible. Hakanto Contemporary is something of a blank canvas on which such artists are able to experiment. A lamba, one could say, to make their own.

Endlessly (2023), Kevin Ramarohetra. Photo: courtesy the artist and Hakanto Contemporary

‘Lamba Forever Mandrakizay’ is at Hakanto Contemporary, Antananarivo, until 18 November.