This August marks the centennial of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which established women’s right to vote in America.

Though the pandemic interrupted many anniversary exhibitions, including the Library of Congress’s ‘Shall Not Be Denied: Women Fight for the Vote’ and ‘Creating Icons: How We Remember Woman Suffrage’ at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, new books and other media continue to explore this history, including Martha S. Jones’s highly anticipated Vanguard (forthcoming in September) and a recent PBS documentary, The Vote. Several museums have also made their exhibitions available online, including the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery’s recent ‘Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence’.

The story of suffrage in the US is more complex than one legislative landmark: it is a centuries-long movement with many intersecting and diverging strands. The material history of the movement reveals many of its priorities and problems, and its relevance to the persisting struggles for equal rights today.

1. Seneca woman’s tunic (c. 1850–70)

Women could vote in North America long before 1920. For centuries, the Six Nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy have followed an egalitarian model in which women have the right to own property and vote. Clan Mothers wield authority alongside Chiefs. This highly decorated calico dress, typical of its period, belonged to Gagwi ya ta (Charlotte Sundown), a member of the Seneca Nation.

Women were partially enfranchised in colonial America. However, after the Constitution was ratified in 1788, women’s voting rights were revoked everywhere except New Jersey. The American Revolution imposed the patriarchal, white supremacist rule that compelled the fight for suffrage.

White American suffragists took inspiration from the Haudenosaunee for many of their proposed reforms. Matilda Joslyn Gage, who also advocated for Native American rights, learned from the Mohawk Nation’s models. Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton looked to the Seneca and Oneida Nations to reform clothing as well as government. The suffragists’ dress reform movement advocated shedding restrictive garments in favour of ‘bloomers’, the reform costume of a tunic and leggings, which resembled outfits worn by Oneida women. Despite these debts, indigenous women did not gain the vote in US elections until activists like Zitkala-sa achieved the passage of the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act.

Seneca woman’s tunic, formerly owned by Charlotte Sundown (1850–70). National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Photo: NMAI Photo Services (9469)

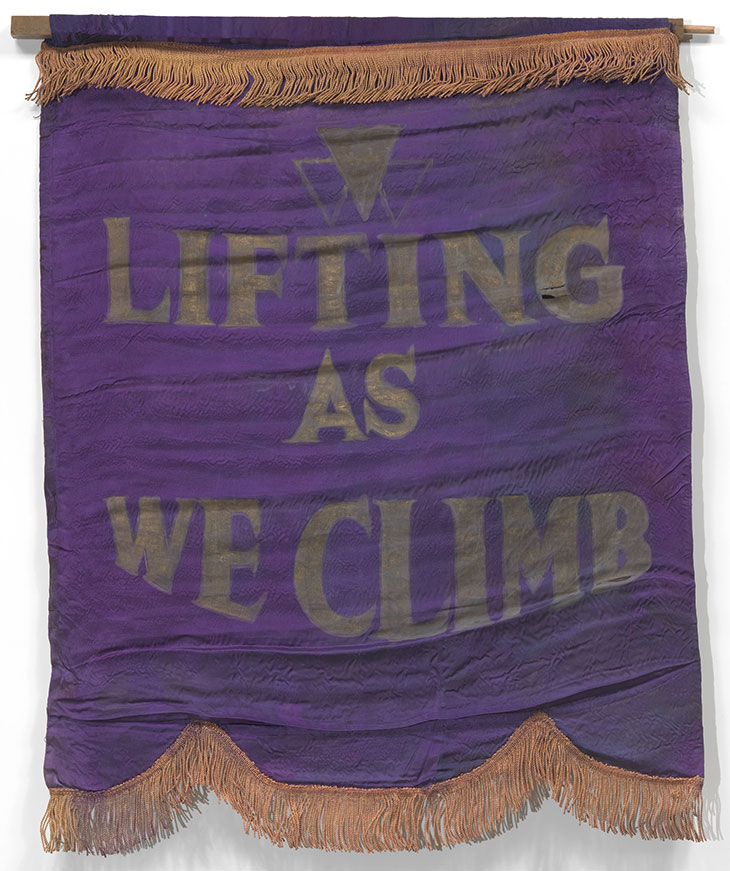

2. ‘Lifting As We Climb’ banner

American suffrage organisations grew out of the anti-slavery movement in the mid to late 1800s. Though some suffragists were also abolitionists, opinions on racial suffrage divided the movement. Two leading groups eventually merged into the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), but continued to marginalise black suffragists in their protests. Black activists, meanwhile, recognised that suffrage was one of many civil rights issues and continued to work for equality across them all.

Led by founder Josephine St Pierre Ruffin and founding president Mary Church Terrell, the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs promoted black women’s social and economic welfare and protested against lynching and segregation. The club’s motto, emblazoned in gold letters on this banner used by the Oklahoma Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, was ‘Lifting As We Climb’. The group conveyed their messages in the same colours used by the national suffrage movement: purple, gold, and white, to symbolise loyalty, hope, and purity. (The colour scheme had been derived from that of the movement in Britain, with gold swapped in for green.) Black suffragists consciously aligned themselves with this message to refute racial stereotypes and lay claim to the social respect they were typically denied.

Much of the suffrage movement’s success came from the grassroots efforts of women’s clubs, which spread across the country as centres for community service and education. National organisations capitalised on this by adopting a state-by-state strategy, using the success of state referendums to build momentum for the Constitutional amendment.

Banner with motto of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (c. 1924). Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, D.C.

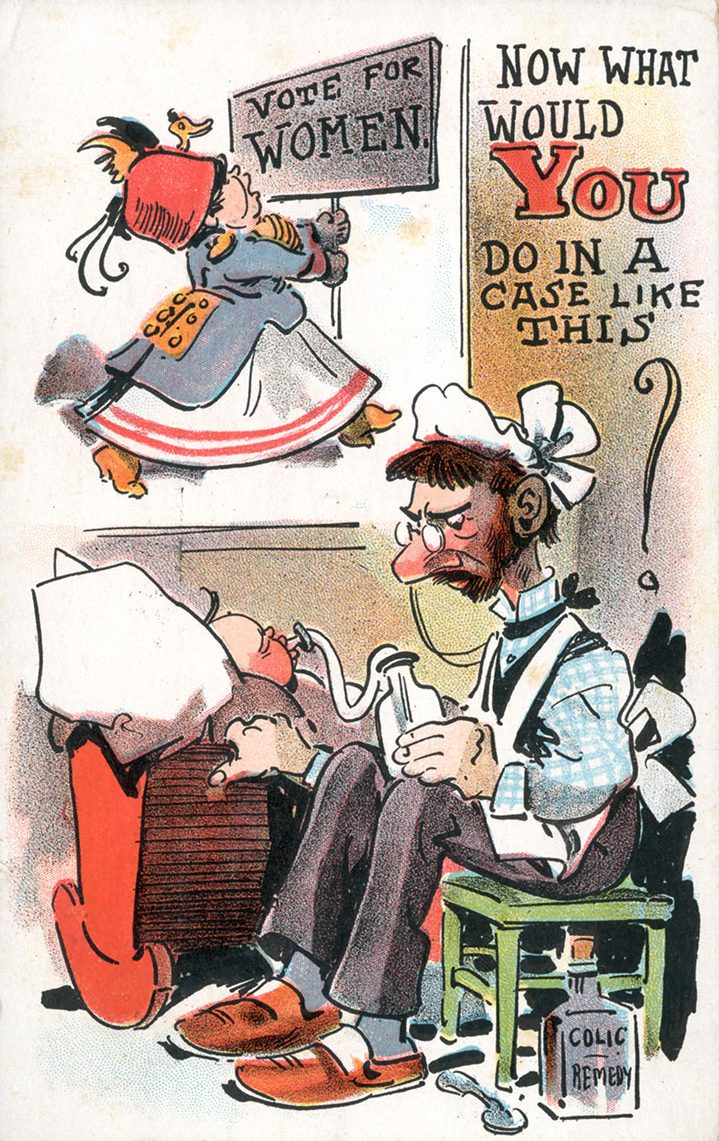

3. Anti-suffrage postcard

Suffragists were lampooned in the press and on postcards, which were accessible and powerful sources of imagery at the turn of the century. Both pro- and anti-suffrage postcards appealed to popular tropes about gender. Anti-suffrage images ridiculed suffragists as ugly, aggressive, mannish ‘old maids’, as in this postcard illustrating a woman’s divergence from acceptable female roles. Pro-suffrage imagery countered with portrayals of stylish, feminine, respectable women (largely white and educated), positioning their success as unthreatening to the status quo.

Negative portrayals of black suffragists layered racist stereotypes over sexist ones. Both kinds of imagery were intended to evoke fears about what would happen if existing hierarchies were subverted: many portrayals circulated of henpecked men ‘stuck’ with childcare duties while their wives gallivanted or campaigned. These dynamics also played out in depictions of children, the twee illustrations sugar-coating their sexist and racist messages.

Postcard (early 20th century), published by Taylor, Platt & Company, New York. Palczewski Suffrage Postcard Archive, University of Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls, IA

4. ‘Jailed for Freedom’ pin

Led by Alice Paul, some American suffragists adopted the militant tactics of the British movement, which achieved the vote in 1918. Paul split from NAWSA to found the National Woman’s Party (NWP) in 1917. She led picketing at the White House (forming the first picket line in the building’s history), during which suffragists were brutalised by police, imprisoned, and force-fed when they went on hunger strike. The ‘Jailed for Freedom’ pin was awarded to the women upon their release. This particular pin was awarded to Lucille Calmes, who was jailed after a ‘watch fire’ demonstration in which suffragists burned copies of President Wilson’s speeches.

The pins’ designer, Nina Allender, was also a political cartoonist responsible for many of the pro-suffrage images disseminated in the weekly newspaper The Suffragist. Allender modelled her pin after Sylvia Pankhurst’s Holloway Brooch, swapping the British portcullis for an American jail cell door, while retaining the oppressive symbolism of the chain. Replicas of these pins are still produced today. The ‘Jailed for Freedom’ pin represents a turning point in US public opinion, as the shock of the protests and the women’s mistreatment swayed voters in favour of the suffrage movement.

‘Jailed for Freedom’ pin, designed in 1917 by Nina Allender; this example presented to Lucille Angiel Calmes in 1919. Photo: courtesy the National Museum of American History, Washington, D.C.

5. Charles Dana Gibson’s illustration for the cover of Life magazine, 28 October 1920

Amid the many social changes wrought by the First World War, the federal government passed the amendment that had first been proposed in 1866.

The drawings of the illustrator Charles Dana Gibson epitomised the ‘New Woman’, the era’s ideal of educated, upper-class, white femininity. On this cover of Life magazine, the female embodiment of America shakes hands with a demure New Woman holding a ballot. This representation largely encapsulated the demographic who had secured the vote.

Though the 19th Amendment contained no racial wording, women of colour continued to be disenfranchised through other legislation. The Chinese Exclusion Act remained in place until 1948; activists like Mabel Ping-Hua Lee fought for suffrage despite knowing they wouldn’t be allowed to vote when the amendment passed. Most barriers to black women’s suffrage would not be struck down until the Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965, after sustained civil rights battles. Today, politicians continue to find ways to restrict voting rights for people of colour. The Shelby County v. Holder decision in 2013 undercut federal ability to enforce the VRA, paving the way for restrictions like those imposed in North Dakota during the midterm elections in 2018, which targeted Native American voters living on tribal lands.

Gibson’s ‘Congratulations’, then, was premature. A century later, the fight for equal rights goes on.

Life magazine cover published on 28 Oct 1920, with ‘Congratulations’ drawing by Charles Dana Gibson. Collection of Ann Lewis & Mike Sponder. Courtesy Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

For more information on planned events and exhibitions visit the 2020 Women’s Vote Centennial Initiative website.