By the time I eventually get to the V&A East Storehouse, I can’t remember what is waiting for me. It’s been a month since I browsed the museum’s ‘Order an Object’ catalogue in a state of mounting panic trying to find the perfect item from a list of 1.2 million. The plan was to make a selection, book an appointment and, two weeks later, head to the new storehouse in the Olympic Park, where my object(s) will be waiting for me. But when I start the process at the beginning of June, the first available appointment is not for another month. That’s why I am travelling to Hackney on the hottest day of the year, trying to remember what I asked to see.

After picking my way across the canal and past flats and a new primary school in this rapidly evolving part of London, I reach Here East, the technology/science hub that was once the Olympic media centre. This is now home to, among other operations, the V&A East Storehouse, a sort of public-access warehouse that contains 600,000 items from the V&A collections, much of which was previously kept in storage at Blythe House in Olympia.

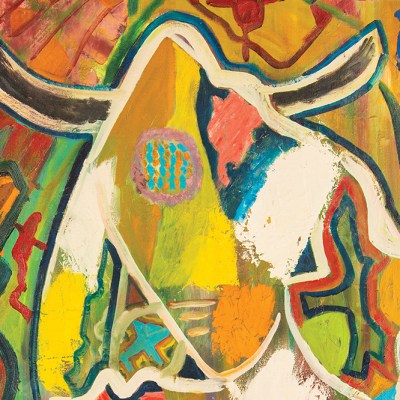

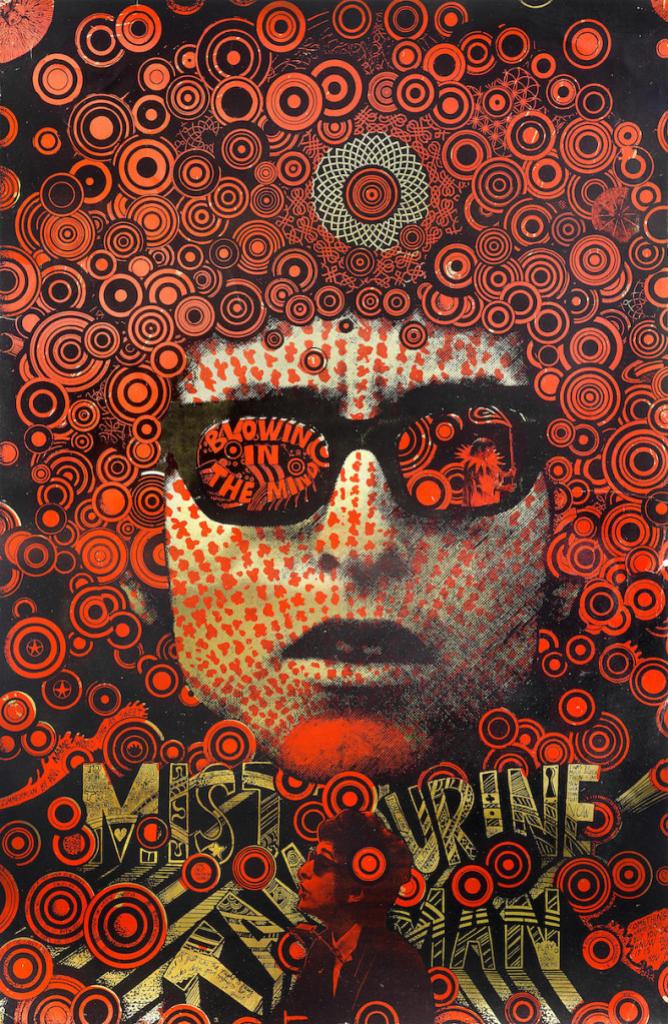

I make my way to the Study Centre on the second floor, where my objects are waiting. The receptionist reminds me what I ordered: a jacket made by design collective The Fool for The Beatles’ Apple boutique in 1967; a psychedelic Bob Dylan poster by Australian artist Martin Sharp, from the same year; and a statuette of Apollo, in honour of this publication. Andrea, one of the Collections Access Managers, meets me in the main study space. She tells me where to find gloves and how to handle the objects, then carefully removes the protective wrapping from the jacket, revealing the gorgeous brocade design. ‘Oh, that’s beautiful,’ she says. Unexpected marvels like this, she adds, are one of the perks of her job.

The jacket is a delight for me, too, the photograph on the website not really able to capture its luminescent beauty. I’m allowed to feel the texture and inspect the lining, but sadly not try it on. The Martin Sharp poster is another triumph. The 1967 red-and-black image of a shaded Dylan – titled Blowing in the Mind/Mister Tambourine Man – is often reproduced, but the dazzling colours and brilliant, intricate detail can only really be appreciated in person. Even when it’s behind a frame, the virtuosity is diluted. As for the Apollo statue, this is a mass-produced trinket that I am asked to handle carefully. I can pick it up and examine the base. In truth, it is nothing special to look at but has a mysterious provenance. According to the catalogue, it was discovered in the collection in 1912, having originally been submitted to the museum in 1873 but rejected as having ‘scarcely any value as a work of art’. It was meant to be returned to the donor but ‘those instructions were evidently overlooked’.

All things said, I am pleased with my selection but, since I wasn’t researching anything in particular, the initial choice was overwhelming. The ‘Order an Object’ catalogue offered me 1,291,257 objects. I froze. Where do you even begin? Fortunately, an easy-to-use filter system allowed me to narrow this down to objects available only at the V&A East Storehouse and ‘View by Appointment’. Now I had 240,306 objects. I got searching.

First, I browsed items related to David Bowie. While there are lots of nice posters and T-shirts, there are not yet any items from his personal archive, which has been acquired by the V&A and will open to the public as the David Bowie Centre in September. This will be a dedicated space within the V&A East Storehouse featuring highlights from the collection of 90,000 items chosen by guest curators, with the rest of the collection available through ‘Order an Object’. In the sifting process, I am distracted by the Sony Memory Stick Walkman NW-MS7, a clunky 2000 update of the classic Walkman that stored 80 minutes of MP3s and was rapidly overtaken by the iPod. My finger hovers over the ‘Order this Object’ button, but I ultimately decide I’ve already seen all there is to know.

The filter function offers an insight into the nature of the collection. Filter by object and there are, for instance, 16,401 photographs and 1,878 vases. Filter by collection, and there are 69,879 items from the Theatre and Performance Collection but just three from the Design, Architecture and Digital Collection. You can filter by material, style, technique, person, organisation and date. I eventually make my choice, on a whim, but for students, academics, artists and enthusiasts of certain eras and disciplines, the attractions of the ‘Order an Object’ system are obvious.

The Study Centre has three large tables and two smaller ones, but there are only two other visitors looking at items while I’m there – one leafing through a wizened book of theatre costumes, the other examining a roll of fabric. From a balcony, visitors peer down. That’s very much in keeping with the building’s founding principle. The V&A East Storehouse, designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, is all about opening the inner workings of the V&A to the public. Imagine a restaurant with not just an open kitchen, but one that lets you poke through the dustbin and store cupboard, nose inside the freezer and then stop to chat with the sous-chef on the way out.

It is a cleverly designed space. Three large square floors have walls stacked with eclectic objects: rococo furniture, chessboards, cardboard cut-outs, ’70s T-shirts, busts and sculptures, a blue plaque for Lilian Baylis, paintings and more – like the world’s most expensive junk shop. Here are items too large to be displayed at South Kensington, including a chunk of the facade of Robin Hood Gardens, a brutalist block of flats demolished in 2017–19. That sits opposite a carved, gilded ceiling from a Spanish palace dating to around 1490. Visitors can sit in recliners and gaze up at this humbling interior while the see-through floor allows the public to walk above shelves filled with paintings and decorated tiles.

The ground floor is for V&A staff. Visitors can watch conservators at work from a glass observatory deck, or stare down at archivists moving items or packing them up for delivery. There’s little in the way of orientation or labels, although a chunky catalogue is on hand for browsing. Instead, the space is populated by numerous cheerful visitor-experience staff, all wearing the same natty uniform and happy to help visitors get the best from this postmodern museum. As I leave, Bill asks if I enjoyed my visit. He tells me he loves it here. ‘Because there are no labels, I’m drawn to things I wouldn’t normally be interested in,’ he muses. ‘It’s just the beauty of each object that catches my eye.’