The February 2020 issue of Apollo is the first to carry a museum restaurant review, republished below. Click here to read more about Apollo’s decision to introduce such articles.

Henry Cole was ahead of the game. In the early decades of the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A), visitors did not so much exit through the gift shop as enter through the cafe – particularly after the grand Refreshment Rooms opened in 1868, replacing a much-ridiculed mock-Tudor refectory that had been designed by Francis Fowke and opened in 1856.

Cole’s vision for the museum, which twinned education with leisure, often stressed the provision of refreshment – conveniently hitching the literal (actual sustenance) to the metaphorical (intellectual nourishment). ‘Let the working man get his refreshment [in museums] in company with his wife and children,’ he declaimed at the Liverpool Institute in 1875, ‘rather than leave him to booze away from them in the Public-house and Gin Palace.’

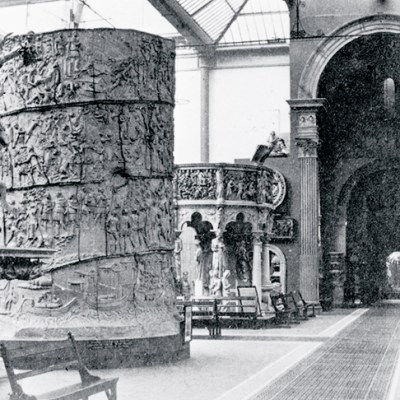

In the late 1860s, the Refreshment Rooms stood just beyond the glass-screened entrance to the museum. Today, as the Gamble, Poynter and Morris Rooms, they nestle – for those entering from Cromwell Road – towards the back of the V&A, which spread southwards towards Chelsea around the turn of the century. Nonetheless, to see these interiors for the first time is to be transported back, in a way that perhaps only the Cast Courts can compete with, into a mid Victorian museum vision that one contemporary writer described as ‘a Palace of Art, devoted to the free culture of the million’.

The most opulent of the rooms, now the Gamble Room, is like a 19th-century English dream of Italy: double-height golden arches, walls thronged with prancing putti and other ‘majolica’ decorations, and a ceiling on which an enamelled grottesche scheme jazzes up large sheets of iron. This room is the antithesis of the tidy design that would become increasingly fashionable towards the fin de siècle but also to some degree its precursor, in the care with which materials were chosen for their washable and fire-repellent qualities. The stained-glass windows, which carry an anthology of alimentary maxims and literary quotations, were installed to conceal the kitchens and other buildings beyond. ‘The whole gives an impression of perfect cleanliness’, reported The Times in 1875.

The Green Dining Room, now the Morris Room, is perhaps the most important artistic achievement here. The young William Morris, who had recently established Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., brought in Philip Webb and Edward Burne-Jones to collaborate on the decoration. With its blue-green scheme, its serene organic patterns, and its playful cartouches of the hunt, it is the most peaceful of the three Refreshment Rooms: an Arthurian forest passed through the fine-meshed chinois of design reform.

Early diners at the South Kensington Museum could choose from the first-class or second-class menu (third-class sustenance was available elsewhere on the site). Jugged hare, steak pie, veal cutlets: it might be a bill of fare devised by Fergus Henderson for St John 150 years later. In the East Dining Room, an iron grill designed by Edward Poynter broiled further meaty treats; this, too, was flanked by easily cleaned tiles painted by women from the National Art Training School in the Delft style.

Alas, Benugo. The first museum to boast a cafe was also the first, in 2004, to contract its catering services to what was then a small chain of coffee shops – and which now runs restaurants at cultural sites across the UK, from Westminster Abbey to the Bodleian Library in Oxford. The annexation of museum restaurants by contract caterers has been inevitable, perhaps, given that the suppliers guarantee revenue for their hosts and thus mitigate the risk of providing such facilities at all. But what of the risks faced by diners?

A small sign hangs outside the V&A Café: ‘Your purchase is vital in helping the V&A to enrich people’s lives as the world’s leading museum of art, design and performance.’ My purchase is ‘roast pork belly, cider & plum sauce’ with two sides (£13.50). The server dumps meat, red cabbage and new potatoes into a soup plate that’s far too small for them; the meal looks a bit like a compost heap on whose upper slopes a fox carcass has been tossed. The potatoes are hard and shrivelled and the cabbage tastes as though it’s been artificially sweetened. It is impossible to tell whether the pork belly has been deliberately slow-cooked or just left in a hot oven for far too long: the flesh is tough and the fat holds lumpy surprises, like bubble wrap smothered in Vaseline. Other diners wander back and forth through the Gamble Room carrying their trays, hoping for a seat to free up so that they can embark on their own adventures.

On a subsequent visit, I head to the ‘Delicatessen’ counter. Venison and cranberry sausage roll with two salads (£10.25), served up on a warm plate. Quaggy pastry shrouds a sausage – a meat torpedo, really – so dense that my knife has to double as a lever to prize it apart. I eat what I can of it in the Morris Room, dreaming of refreshment.

From the February 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.