From the January 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Nearly 150 years after his death, Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (1814–79) is a figure whose reputation might, at best, be termed complicated. During his lifetime, he was the prime restorer of France: the master of its Gothic revival and the saviour of monuments such as Notre-Dame, Carcassonne and the Château de Pierrefonds. In the decades after his death figures including Anatole France and Auguste Rodin lined up to condemn him for ‘defiguring’ and committing ‘sacrilege’ against the very same buildings. At best he was a revivalist, at worst a vandal; and the transformed buildings he left behind were exercises in inauthenticity. By the time the centenary of his death came round posterity had still not made up its mind. The year would be marked on one hand by a landmark exhibition in his honour at the Grand Palais and on the other by the official decision to begin ‘derestoring’ his work at Saint-Sernin in Toulouse.

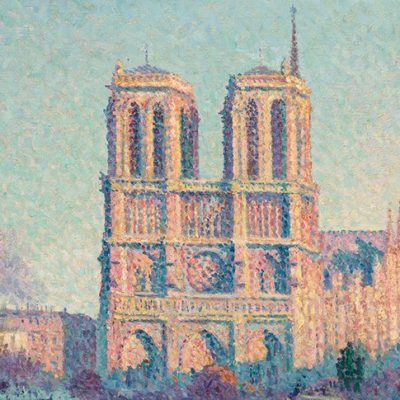

Almost half a century on again, the dust has yet to settle. In the aftermath of the fire at Notre-Dame in 2019, debates raged over how to handle the interventions Viollet-le-Duc had made during his work at the site – above all the monumental spire with which he had crowned the edifice. While the fire is long extinguished and the spire rebuilt, the debate smoulders on. The appearance, though, of ‘Viollet-le-Duc: Drawing Worlds’ at New York’s Bard Graduate Center (28 January–24 May), curated by Barry Bergdoll and Martin Bressani, puts the man and his creations in a different light. Alongside ‘Gothicisms’ at Louvre-Lens (24 September 2025–26 January), which examines the long history of the gothic from the 11th century to the present, it offers a chance to look with fresh eyes at a figure whose impact, for all its controversy, is still being felt today.

For fans and critics alike, there is no denying the grandeur of Viollet-le-Duc. Seen through the eyes of a smaller age, he appears less as an architect than an incarnation of 19th-century France in all its equivocal magnificence. Alongside his main role, he was also an artist, designer and administrator, theorist, teacher and historian, with sidelines in military strategy, archaeology and even glaciology. For industry alone, it is hard to think of his equal. His uncle described him as a ‘drawing machine’ and there remain some 20,000 sheets of his work in the Médiathèque du patrimoine et de la photographie alone, before one accounts for the thousands of illustrations in his books and articles. Two titles among the dozens that make up his writing output, the Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle (1854–68) and the Entretiens sur l’Architecture (1858–72), comprise 12 thick volumes. To keep up the flow, he entered his studio at seven each morning, received visitors from nine to ten, then drew until dinner at six, before retiring to his library at seven to read and write until midnight. In his monthly visits to every building he was working on, he made sure to travel at night, in order to maximise his working hours. Even so, it is hard to imagine how he managed.

For all this, he seems doomed to be remembered, and often condemned, for a single sentence. As he states under the entry for Restoration in the Dictionnaire raisonné, the restorer’s role is to ‘re-establish [a building] in a complete state which may never have existed at any given moment’. Out of context, it is the kind of thing that would never fly in a world more given to historical responsibility than individual hunches, and it prompted discomfort even among Viollet-le-Duc’s contemporaries. When Eugène Giraud came to caricature the architect in 1861, he figured him as a colossus, dapper in white tie and tails, bearing a cathedral in the palm of one hand; the 19th century towering above the 13th with Olympian presumption.

To look beyond the quotation, though, is to see a more thoughtful figure, animated not by ego but by a passion for architecture that looked both forward and backward. The arch-medievalist was also a modernist who saw understanding the past as ‘one of the most active means of generating progress’, the sign of a Europe ‘walking at double pace towards the destinies to come’. He goes on to mock the architect who might refuse to install stoves in a medieval church for forcing ‘the faithful to catch colds from archaeology’, and to advise above all else that the restorer understand each building as an organisme, whose delicacy had to temper every manoeuvre they made. Taken corporately, the dictionary’s innumerable dissections of the details of medieval architecture present less an egomaniac than an autodidact, determined to absorb and transmit every iota of a knowledge on the verge of disappearing altogether.

If ego played its part, it is understandable. From infancy, Viollet-le-Duc was set apart. Taken ‘from the cradle’ for training by his uncle Étienne-Jean Delécluze (1781–1863) – an art critic and veteran of Jacques-Louis David’s studio – he became a prodigy. At 18, court connections allowed Viollet-le-Duc to take commissions from King Louis Philippe himself, which would be shown at the Paris Salons of 1835 and 1836. Avoiding the usual parcours through the École des Beaux-Arts, he used the money to fund two years travelling though Italy. The hundreds of drawings completed on the trip are a record of a man trying to devour the history of architecture in one gulp.

The selections in ‘Drawing Worlds’ show his attention to both the drama of life within buildings and the technicalities of their creation: a celebration of mass pierced by a sunbeam in the Palatine Chapel in Palermo; elevations of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence and the Doge’s Palace in Venice; the minutiae of ceiling decorations in Messina. The centrality of drawing to Viollet-le-Duc’s outlook, as Bergdoll and Bressani note, cannot be overstated. In his pedagogical writings, he would elaborate a theory of it as a fundamental means of understanding the world. To really see (voir), rather than to merely look, ‘is to understand, it is to oblige the intelligence to become aware of objects’.

One of the things Viollet-le-Duc understood in Italy was that buildings survived only while life made use of them. The pieces he submitted to the Salon of 1840 would embody the insight in a pointed equivalent to the restoration projects required of the École des Beaux-Arts students who won the Grand Prix de Rome. Viollet-le-Duc envisaged the restoration of the amphitheatre at Taormina, presented in two extraordinary before-and-after panoramas. The first shows it in near monochrome watercolour, as he saw it at sunset in June 1836: caught between the mountains and the sea, it is a barren declivity, limned by a decaying curve of arches and the remnants of a colonnade. In the second, as if the restoration has extended to the landscape itself, everything is revivified: Etna emits a plume of white smoke, the sun sends a soft golden column down the centre of view and in the foreground, the theatre is crammed with attentive spectators on their seats, rapt before a drama. Restoration, peopled and bustling, winds back time to a perpetual high-noon of Greek civilisation.

Classical ruins, though, were never Viollet-le-Duc’s métier. His lodestar was the medieval and the urgency that motivated him was the risk that France would destroy its own heritage for good. As he entered his teens, the country was in the grip of a paradox. On one hand, the Revolution, the Enlightenment and Napoleonic centralisation had hollowed out the churches, fortresses and monuments of old France and left them purposeless; on the other, those same churches and monuments were being valorised simultaneously by Romantic investment in the sublime and the nationalist belief in a time that expressed the true spirit of French brilliance in art and arms. Demand for books such as Charles Nodier and Baron Taylor’s monumental Voyages pittoresques et romantiques dans l’ancienne France (1820–78), illustrated by Viollet-le-Duc and others, was high, but the very sites they were immortalising were disappearing fast.

As Victor Hugo fulminated in two polemics published in 1825 and 1832, it was not just neglect and decay at work, but active destruction: buildings demolished by local functionaries, sold off for building materials, and even shipped away to English collectors repeating ‘Lord Elgin’s profanations’ on French soil. Worst of all, the state and its institutions were doing nothing to stop it. While the wreckage of the past tumbled in broken piles on the ground, ‘an individual […] who styles himself architect of the École des Beaux-Arts […] walks stupidly over it every day’. Time, in Hugo’s words, to declare ‘War on the Demolishers’.

For Hugo, as for Viollet-le-Duc, it was not simply the ‘old France’ at stake but the medieval period specifically, the great era of the Gothic. As pictured in Hugo’s smash hit Notre-Dame de Paris (1831), that was a period a modern, monarchical, post-revolutionary France could look to as a mirror and model, the spirit of which was expressed above all in its architecture. The moment when the cathedrals, ‘invaded by the bourgeoisie, by the town, by freedom, escape the priest and fall under the power of the artist’; the moment when there reigned ‘for thought written in stone, a privilege entirely comparable to our current freedom of the press’. A moment when, in Viollet-le-Duc’s eyes, architecture freed itself from ossified habit and perfected an art ‘so supple, so subtle and liberal in its means of execution, that there is no programme it cannot fulfil’.

While Hugo was rechristened ‘HUGOTH’ in the pages of La Charge and pictured as a swollen head blooming from crumbling stonework, his obsession helped change the course of architectural history. The appointment of Hugo’s friend Prosper Mérimée as Inspecteur General des monuments historiques de la France was a pivotal moment for the posterity of the Gothic and for Viollet-le-Duc. As a close associate of the new Inspecteur, the young architect became a key player in the war against the demolishers.

Viollet-le-Duc’s centrality to the movement that followed makes it less surprising that he went so far in his work than that he found time to achieve anything. During the years spent restoring Notre-Dame itself (1844–64), he travelled the length and breadth of the country, overseeing as many as 20 other projects at a time, including the restoration of an entire medieval town at Carcassone. He would even put in a stint as chief engineer on the Statue of Liberty, laying down crucial elements of the design that would, after his death, be completed by Gustave Eiffel. Alongside the endless planning, travelling and writing, he found time for expeditions in the Alps and endless, omnivorous drawings.

What is truly extraordinary, though, is not the breadth but the depth of his work. He was not a ‘big picture’ architect so much as an every picture architect. The surviving plans show him less as trying to capture the spirit of a period than as trying to capture the skills and inspiration of every individual craftsman it birthed. Every detail was under his control, from structural design down to the smallest flourish. Among his most beautiful drawings are the sheets of designs for the gargoyles he returned to Notre-Dame: hundreds of them, every single one given an individual physiognomy.

It is perhaps these, and the ‘chimeras’ that populate the cathedral’s parapets, that encapsulate Viollet-le-Duc’s brilliance and impact. Convinced of the necessity of gargoyles in saving Notre-Dame’s masonry, and taking inspiration from the eroded remnants of the cathedral’s originals and the starring role given to them in Hugo’s novel, he set out to create an entire new bestiary of waterspouts and statues. The results would create the image that has defined Notre-Dame ever since: the so-called Stryge looking out from its parapet at the changing city below. Immortalised first by Charles Meryon’s etching in 1853, as well as by Nadar, Brassaï and others, the pensive demon would become the defining image of the cathedral and even of the Gothic itself. Like his fellow sculptures, this ‘grotesque’ is the remarkable product of an architect who was simultaneously a hard-headed project manager and a fantasist, a rationalist and a dreamer.

Seen through this lens, the debates over authenticity seem beside the point. No one would accuse Hugo’s Notre-Dame, with its wild digressions, Grand Guignol and historical inaccuracies, of being inauthentic. The novel works still because of its brilliance: the pleasure of spending time with an extraordinary imagination, watching it grind its axes and enjoying the sparks. To look at Viollet-le-Duc’s drawings is to be reminded that the same might apply to him. His restorations may be chimeras just as ‘Le Stryge’ is, but that should not be taken as a condemnation. As he wrote in his Entretiens sur l’architecture, we all know that centaurs never existed, but if an artist can make them seem real, ‘why take that possession away from me?’ After all, ‘What more will the savant know when he has proven to me that I am taking chimeras for realities?’ Nothing at all, while the centaur will walk on through the forest unperturbed.

‘Viollet-le-Duc: Drawing Worlds’ is at the Bard Graduate Center, New York, from 28 January–24 May; ‘Gothicisms’ is at the Musée du Louvre-Lens until 26 January.

From the January 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.